Choosing a consultant

NZFFA Information leaflet No. 16 (2005).

I have always been an advocate of hiring a consultant when the time comes to harvest and market your woodlot or forestry block. People often ask me why I do not get a portable sawmill and market my own timber. Having harvested several small blocks now, I am convinced that to get the best value from your woodlot it pays to get in a consultant – one with the expertise in all aspects of harvesting and marketing. There are too many horror stories out there about damage done, messes left behind and, worst of all, non-payment for logs at the end. It never ceases to amaze me how a farmer can quibble over a couple of cents per kilo for their wool or a dollar or two for cattle and sheep at a sale, then let some cowboy come in and take their trees often worth thousands.

So how do you find a good consultant? For the farm forester or small woodlot owner, word of mouth still seems to be the best method but use companies with good track records. The NZ Institute of Forestry has a register of professional forestry consultants that are required to meet their standards.

Consultant checklist

A consultant should be able to give good advice on, and organise the whole job. The following points should be discussed with your consultant before a contract is agreed:

- Advice on roading and type of access tracks required. In our case, despite a flat road and good track, 300mm of rain just brought everything to a halt.

- A pre-harvest assessment. When selling a block of trees, you must know what you have to sell. You need to know the area and how many trees you have. If it is a small block, it’s a fairly simple job to physically count them. If it is a very large block, it may be feasible and economically worthwhile to have an independent log study/assessment conducted before you start. Once you have all the data, you can call for quotes or tenders.

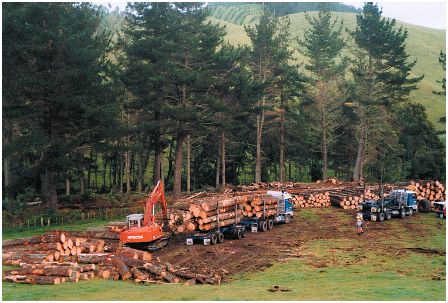

- Hiring experienced logging crews with the right equipment. Cutting down trees and logging is a job for professionals, particularly when you remember that forestry has one of the highest accident rates in the country. Farm woodlots are notorious for being in awkward corners with very big trees and edge trees with heavy tops which will need to be winched back. Our trees averaged between 3 and 4 tonnes each – not a job for the normal farm tractor. Our woodlot was fairly typical of a lot of farm blocks that contractors have to contend with: long and narrow with a stream on one side and a good fence on the other. Despite this there was no slash or debris, not one tree went in the creek and no fences or gateways were damaged. This is proof of a job well done.

- Advice on transport and organising logging trucks. It is important logs are moved as soon as possible after cutting down, particularly if the weather is wet and humid. Logs will deteriorate rapidly if left lying around. Sap-stain will lead to down-grading, especially in the higher-value pruned butts.

- Assessment of log grades and matching logs to suitable markets. Prior to logging, your consultant will measure tree diameters, tree heights, pruned butts and top log lengths. From this data you will get an estimate of volumes and grades. Once this is determined, your consultant can then approach the markets to find where the best financial returns are for the grower. The logging crew also needs to have someone competent at grading logs. The grades can and do change often, which can make things very difficult and leads to unnecessary waste. Log grades can relate to pruned butt length, small and large end diameters of log, branch size, or to what the market requires at the time. In our case we had eight grades of logs on the skid site.

- Advice on safety and compliance with OSH regulations.

- Obtaining resource consents when required.

The contract

You should sort out who is liable for property damage to property gates and fences at the start, as this can be very expensive. Similarly, terms of payment for the contract must be agreed upon. A written contract is negotiated with all parties involved including the logging gang, truck company and so on. Once this is finalised and signed by all parties, the consultant takes responsibility for sorting out any problems that arise between the landowner and the contractors.

While a written contract is essential, it is equally important that a good verbal dialogue be maintained throughout the job between the landowner, the contractors and the consultant. Few jobs will run smoothly all the way. There is always some hold up – the weather, equipment breakdowns, changes in log grades, price fluctuations – and these can combine to fuel the tension on site.

I am very keen on the incentive system where everyone can win. Screwing the contractors achieves little in the long term. It puts pressure on the workers, and leads to shortcuts and accidents.

This article by Geoff Brann appeared in the February 2000 issue of the New Zealand Tree Grower. Photographs reproduced from New Zealand Tree Grower, February 2000.

A few pointers about contracts

Is a verbal contract legally binding in all circumstances? No, but most verbal contracts are binding. The main exceptions are contracts dealing with interests in land including forestry interests in land, and guarantees. The law requires that these be written. For all contracts there must be certainty about who is contracting and what each side is promising the other. Ensuring that it is in writing makes it easier to prove what was actually agreed and is a usual precaution to follow. Also there must be actual agreement – an arrangement to agree something in the future will not be enforceable.

How watertight does a written contract need to be? What information must it contain? This will vary from contract to contract. As a minimum, the contract should identify the parties properly, and what each is promising the other. This can include the services to be provided, the goods sold, the price paid, the timing, manner and standard of performance, the method and timing of payment, the consequences of breach or delay, and how disputes are to be resolved. But if the contract is written, you should be sure it contains all the terms agreed – you may not be able to include later items which were discussed in negotiations but left out of the written version. Usually, the more that has been agreed and spelled out unambiguously, the less room there is for dispute later. Investing time to negotiate a good working relationship before you enter the contract, and careful drafting of the document itself, are usually more productive than arguing about what you intended after it has turned sour. Uncertainty and ambiguity are the enemies of good contractual relationships, both in the field and in court.

This note by Keith Catran, senior solicitor with Russell McVeagh, appeared in the February 2000 issue of the New Zealand Tree Grower.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand