Form pruning deciduous hardwoods

NZFFA Information leaflet No. 23 (2005).

How often have you been asked by someone “What should I plant on a plot of land where I want to grow trees for my grand children – but I do not want to plant radiata?” Only too often? A standard reply is “If there was an obvious answer to that one, I would have planted it 25 years ago”. However, even if there is no ‘wonder tree’ (other than radiata?), there are a range of other species that are attractive to grow, and many of us would like to maximise any possible timber potential. Amongst these species are the deciduous broadleaves such as ash, oak, elm, sycamore, walnut, cherry and chestnut.

The challenge

With this in mind, the two writers sat down almost 10 years ago to design a trial to look at early silvicultural options for improving the timber potential of deciduous hardwood trees. We knew that in the home ranges of these species, silvicultural regimes often begin by recommending initial spacings of 2500 to 3000 seedlings/ha – dense stockings aimed at forcing acceptable form and branch size. Our thinking was that most potential New Zealand growers (probably farmers) could neither afford this high initial cost, nor were they likely to have the large areas of good soil and shelter needed for traditional broadleaf plantations. Most would be more attracted (mentally, physically and financially) to planting a few trees in scattered sites, rather than many trees in a single plantation. However, if it was not going to be possible to get good bole form and branch control by close spacing (as in plantations), then some other simple, individual tree technique was needed to improve timber quality.

The trial

So we designed a trial where the aim was to grow, as quickly as possible, a target sapling tree which we described as “A healthy tree with a single, straight, defect-free, stem of at least 3m length”. We managed to assemble sufficient acceptable seedlings of nine deciduous hardwoods – Algerian, sessile and Turkey oak (Quercus canariensis, Q. petraea and Q. cerris respectively), English ash (Fraxinus excelsior), Dutch-elm-disease-resistant elm hybrid (Ulmus ‘Loebel’), wild or Gean cherry (Prunus avium), sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa), Paulownia fortunei, and Robinia pseudoacacia (‘Jaszkeseri’ clone). Three of our sponsors, the North, Central and South Canterbury branches of the NZ Farm Forestry Association, asked if some native species could be included, so we added black beech (Nothofagus solandri), kahikatea (Dacrycarpus dacrydioides), totara (Podocarpus totara) and kanuka (Kunzea ericoides). And, of course, we had to include radiata pine and macrocarpa as benchmarks. That made 15 species in total – although the Algerian and Sessile oak turned out not to be pure species, and included many hybrids with the common English oak, Quercus robur.

The trial site was in the Forest Research Institutes’s nursery off Oxford Road in Rangiora. The site is flat, with a deep, fertile, Waimakariri silt loam and has a mean annual rainfall of 650mm. Limited space meant that the trial had to be divided into a north and south block. The north block was exposed with little shelter, while the south block was well sheltered. Planting was carried out in mid-August 1991. Trees in all treatments were given weed control for the duration of the trial.

Six silvicultural treatments (replicated five times) were tested:

- Control – left untouched

- Form pruning – leader training and branch control

- Plastic KBC® tree shelter (1.2m) + form pruning

- Plastic KBC® tree shelter (0.75m) + form pruning

- Plastic Tubex® tree shelter (1.2m) progressively raised up to 3m as tree grew

- Coppicing plus 1.2m tree shelter (yr 2) + form pruning

It soon became clear that the most important treatment was form pruning, which is the focus of this article. Other results, particularly relative to the use of tree shelters, are only summarised below and will be detailed in a later article.

Results– height growth, shelters and target trees

Many trials seem to attract Murphy’s Law, with unforeseen problems regularly arising. This trial was fortunate enough to have few such problems and was a joy to attend and watch maturing. Some species grew over 1m a year, but as the species blocks were not replicated, and the north and south sites offered different growing conditions (particularly relative to wind exposure), comparisons between species could only be viewed indicatively.

Shelters

KBC® tree shelters improved initial survival principally by eliminating hare and rabbit damage. Tree shelters also significantly improved early height growth, although this advantage over control trees declined over time and was considerably less apparent by age 5. Stability of trees with standard (1.2m tall) shelters was not a problem with deciduous species. However, it was a major problem with the evergreen species, radiata and macrocarpa, and three of the native species, kanuka, totara and black beech. Raised shelters were tried only on wild cherry, ash and Algerian oak, and in all cases promoted instability.

Stems soon became too weak to support their crowns and had to be given artificial support.

Achieving target tree status (‘straight defect-free stem of at least 3m length’)

For most species there was at least one silvicultural treatment which promoted the majority of trees to reach target specifications within 5 years. Some species achieved it within 3 years. The slowest were the four native species where only 13% of the black beech reached target tree status. The most influential factor was form pruning.

Form pruning

Form pruning involved leader training and branch control. Of these, leader training was the most important.

Leader training

This was carried out annually from year one in spring and sometimes again in mid-summer. It made a major difference to stem straightness, and to the number of trees reaching target specifications within the span of the trial.

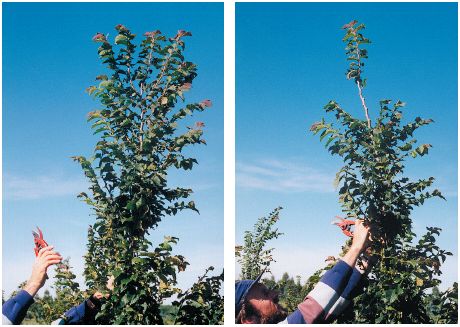

Leader training involves removing or tipping back competing leaders to promote a single straight, vertical leader. If carried out at the right time in spring, when young growth has not lignified (become woody), the work required is minimal.

It is not unusual for winter frosts and insects to kill the terminal bud on the leader of a deciduous tree, and once growth commences, a number of secondary buds will begin competing for leadership. If left untouched a multileadered top usually results. However, a few seconds of pre-emptive pruning with a pair of secateurs when the young shoots are only 5 to 10cm long, is often sufficient to turn a potential problem tree into one of desirable target form.

Small scars created at this time of the year quickly heal. A second visit in midsummer may be needed to remove later development of competing leaders, but if the spring training has been done correctly, repeat visits are not normally needed. As the trial’s target tree required a straight stem only to 3m, no leader training was attempted above this height.

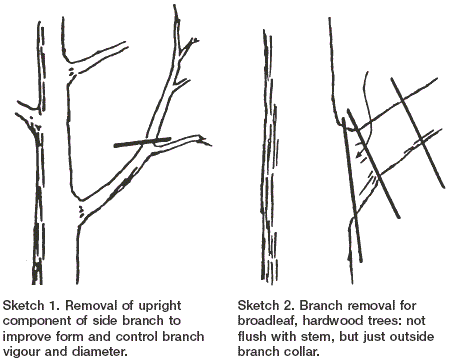

Branch control

Branch control was initiated around year 3 and directed at the larger branches, particularly those with ascending habits. The main focus was on the larger branches in the lower half of the tree, but attention was also paid to steeply ascending branches in the upper half, as these tend to be more vigorous than horizontal branches, and often end up competing with the leader. Treatment involved either removing their upright components or pruning off at the branch base if they had reached a basal diameter greater than 2/3rds that of the main stem (at junction) or, in later years, if they reached 30mm diameter. A home-made 30mm gauge was used to determine when this critical branch size was exceeded.

Branch control was initiated around year 3 and directed at the larger branches, particularly those with ascending habits. The main focus was on the larger branches in the lower half of the tree, but attention was also paid to steeply ascending branches in the upper half, as these tend to be more vigorous than horizontal branches, and often end up competing with the leader. Treatment involved either removing their upright components or pruning off at the branch base if they had reached a basal diameter greater than 2/3rds that of the main stem (at junction) or, in later years, if they reached 30mm diameter. A home-made 30mm gauge was used to determine when this critical branch size was exceeded.

Determining whether to shorten or remove a branch before it reaches 30mm in diameter can be difficult, because if green crown surface area is reduced too severely, diameter growth will slow up significantly. For this reason, no more than one third of the total foliage area was ever removed in any one season, and if there was any doubt, shortening or tipping (removal of the outer half of a branch) was preferred.

Branch control was carried out in late winter or early in the spring at the same time as leader training. This was not only practically convenient, but at this time of the growing season occlusion of pruning scars was most rapid.

Branches were not removed ‘flush’ as with radiata pine. They were cut off just outside the branch collar, or swollen area at the base of the branch. This is important as, if cut flush with the stem, the healing process is uneven and considerably slowed, and there is more opportunity for rots to set in. No pruning pastes were used, as these days it is considered to be an unnecessary expense if pruning is properly carried out (Rumour has it that arboriculturists in Christchurch and Auckland use pruning pastes only in Fendalton and Remuera respectively!).

Discussion

When discussing this trial, the authors are often asked “Why only prune to 3m?” This question usually comes from radiata pine growers, who always target 6m as the pruning height. However, pruning slower-growing species (such as deciduous broadleaved hardwoods) to 6m takes much longer than with radiata pine, and is also more complicated due to the spreading, multi-leadered habit of most broadleaved species. In addition, it can be difficult to reach a growing tip above 3m, as leader training is carried out long before the tree itself is strong enough to support a ladder plus pruner. Furthermore, most hardwood timber is likely to be grown for specialist use in the likes of furniture, or as veneer, and long log lengths are not a prerequisite for such end uses. Buyers of hardwood timber in the Christchurch area are more than happy with quality logs of 3m in length. This height can be achieved relatively easily, and once reached, the crown of the tree can then be left to grow unhindered and in so doing will ‘fatten’ out the butt log in the shortest time.

Pruning to greater heights is certainly not discouraged, but should only be attempted if both desired and readily attained.

With broadleaf species, far more attention needs to be paid to form pruning. This system, involving leader training and branch control, is very similar to that promoted for Tasmanian blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon) by Ian Brown (1993 and 1997) and Forest Research (1995). Brown found that leader training took very little time or effort but led to dramatic improvements in blackwood form, and eliminated the need for a nurse crop. Forest Research advocated the improvement of timber potential by annual form pruning and the use of a 30mm gauge for determining which branches to remove.

Although this article is promoting the growing of a straight, defect-free butt log, the writers would like to stress that they are well aware that many broadleaf trees are grown as much for amenity purposes as for any commercial gain.

And a twisted stem with large lower branches may have more amenity value to some growers than a straight stem. After all, such trees can be ideal for the grandchildren’s tree huts.

Therefore, the message from this article is not only trying to promote the best form for a timber tree, but also informing growers that they can be the boss as to the shape and form of virtually any tree. Form pruning may be a means to producing a quality timber log, but the same principles can be applied to producing a tree for a whole range of end uses. So, when you next plant a broadleaf tree, think about its purpose and the shape that would best meet that end use – then use your secateurs to help make that vision into reality.

Conclusion

The major finding of the Rangiora deciduous broadleaf silvicultural trial – that leader training and branch control are critical to the consistent growing of quality timber butt logs – is not only practically useful, but entertaining as well.

It is entertaining because most tree growers love using secateurs and pruners (unfortunately, this love for pruning is often accompanied by a hate for thinning!) and they welcome any excuses to go outside and exercise their arboricultural inclinations. The writers hope for just this – that the article encourages growers to switch more attention to their broadleaved trees, in the form of leader training in particular. Remember, just a few seconds work in the spring can make all the difference between a quality log which could be worth considerable money to your grandchildren and one which may only attract attention from your local wood turner (but only for small sections of the tree) and the firewood merchant.

This article by Nick Ledgard and Miles Giller, appeared with diagrams and photographs in the August 1999 issue of the New Zealand Tree Grower.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand