Containerised trees - what time to plant

NZFFA Information leaflet No. 4 (2005).

Introduction

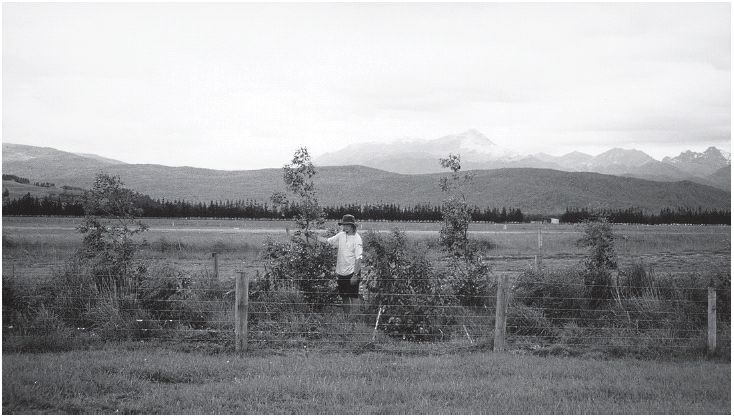

Over some 16 years we have advocated and promoted the planting of containerised trees over late spring and summer with outstanding success in survival and growth rates. During the summer of 1998/99 we really put our concept to the test by planting on severely moisture-deficient sites that had caused mortality in established trees up to 20 years old. One planting was undertaken in temperatures that reached 35°C in the shade! With the exception of one site that we abandoned before completion, the results were outstanding.

In this article are some observations and techniques we feel should help make the concept of spring and summer planting more widely adopted.

The importance of roots

With the trend in garden centres towards emotional sales based on foliage and flowers, the importance of roots is often totally overlooked. To me, the roots are the most vital part of the tree, as initial establishment through to eventual tree stability are critical for success.

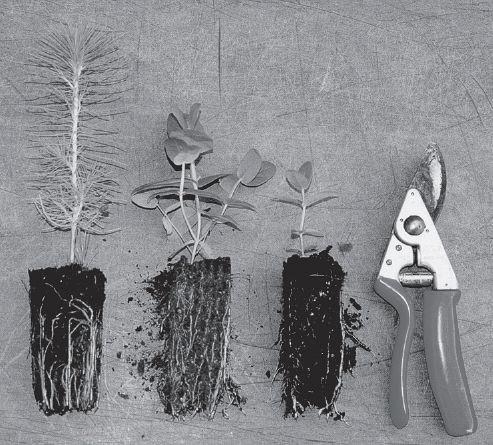

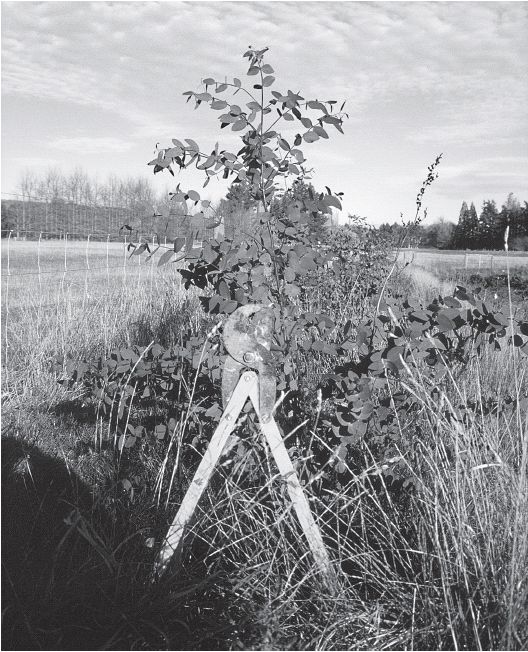

The trees we plant – which may include containerised eucalypts, conifers, poplars and silver birch – are quite small but have self-contained root systems that may in mass equal the stem and leaves. Compare this with your 2m tall specimens perched precariously in bags, with stability reminiscent of a picnic umbrella in a gale. If we consider the tree too tall we snap it back, often quite ruthlessly, to balance the roots with the foliage. The greater the leaf area, the greater the transpiration. The only way the plant can hydrate is through the roots, so balance is critical.

All nurseries I am familiar with are located in relatively sheltered climes with much money spent on enhancing the environment to create a microclimate relatively free from wind and temperature extremes. I have always found it difficult to understand why nurseries recommend winter as the best time to remove these pampered containerised stock and plant them in a hostile, cold environment where animals are foraging for just the sort of tasty morsels these nutrient-rich trees provide.

In Southland, this vulnerable period may be three or four months. Compare how trees establish in nature. Over-winter conditioning and subtle changes in temperature, light and moisture break the dormancy of the previous year’s seed to enhance germination just when conditions are ideal. This enable the seed to grow rapidly before exposure to its first winter, and better handle the vagaries by due hardening off in the autumn. Have you ever tried to pull these trees out mid-season and seen their huge root system? I often get clients wanting instant tall trees for shelter not appreciating that such trees would each require at least a cubic metre of soil to hold the root system.

Ground preparation

To guarantee a high rate of tree survival after establishment it is imperative that ground preparation is of a high standard.

Deep ripping with a winged ripper is a well proven method of site enhancement, as is cultivation over the rip. There are several reasons for this:

Temperature

When you plant a tree, exposing the bare soil creates a much freer conduit between ground temperature and air temperature. Even in Southland, the ground temperature rarely reaches freezing and this higher ambient temperature goes some way towards raising the air temperature, which can drop to -12°C at ground level during some winters. A late frost, the greatest enemy of tree establishment, can be completely negated by bare soil. Mulching, normally beneficial in other ways, can cause severe losses due to frosting.

Chemical interaction

Most tree planters regard weed control as removing or killing existing vegetation to minimise the effect of competition for nutrients and moisture. While obviously a factor, it is of relatively minor importance. Of greater importance is the effect of allelopathy, the term used to refer to certain biochemical interactions between all types of plants, including micro-organisms.

All plants to some degree, secrete chemicals from their roots, often to repel competing roots from other plants, be it grass or clover. These chemicals can remain for some time after the plant has been killed. It is important therefore, to remove the turf, dead or alive, and plant in the loose soil beneath.

Good, deep ripping will completely shatter a wide deep profile. Cultivation and thorough mixing of the turf profile with the soil can also suffice. Roots also move rapidly through areas of loose soil and will not enter areas without any oxygen such as tight clays or areas with a high stagnant water table. Ripping will ensure a rapid root run and efficient scavenging of nutrient. On average sites, no amount of fertiliser will achieve better growth than good site preparation.

Once the tree is planted with the self-contained, well soaked root-ball, we find that root growth is more spectacular than top growth. We have observed 1cm of root growth from all growing points five days after planting. Weed control during this critical phase is paramount as germinating weeds will race the tree roots for areas containing nutrient and moisture. We have examples of eucalypts planted during late October having a 2m diameter root mass by May where total weed control was achieved. Interestingly, the tree was only one metre tall but ready to achieve 2m or more growth the next season.

The thatch effect

Assuming you choose to ignore the above recommendations and continue the traditional spray/plant or plant/spray method, be aware that dead turf, particularly from older pasture, is an extremely effective thatch. Once dry, it will take rain of monsoon proportions to moisten it. It is amazing that any trees survive. Ripping fell into disrepute among some planters because the heave caused by ripping combined with no turf removal or cultivation creates a profile like the roof of a house – it is just as effective in shedding rain. Get rid of this turf.

Pamper the tree

By December, the tree in the nursery can be putting on phenomenal growth but so is its wild cousin. Forget about hardening off stock, but a little help will get it through those summer gales. Make sure the tree is planted in a depression by removing the turf and placing it on the upwind side of the tree. The tree will adapt quickly to the site while receiving early cost-free shelter.

Effective weed control

By planting during spring and summer the site will have a generous growth of weeds. I have noticed that in Central Otago an apparent paucity of ground cover can disguise a solid underground root system; the poor moisture retention of the soils dictate that a substantially greater root mass is needed to support the leaves above, and it is the weed roots that are the real problem. Winter spraying often creates a seed bed for masses of thistles, but if growth is vigorous, they are easy to control with a later spray. Make your spot at least 2m across for the reasons explained above. The smaller the spot, the less the early growth of the tree seedling.

It is my experience that when you plant over summer without following the above steps, the tree is likely to die when it comes under extreme moisture stress. The higher rate of transpiration of larger trees puts them under greater pressure, and without adequate weed control the roots will quickly extend into the pasture zone. This sharing of moisture with other often apparently innocuous grasses will cause earlier soil moisture loss, associated tree stress, and eventual death. By contrast, a small newly planted tree has relatively low transpiration needs compared to its big brother, and on a carefully prepared site it has all the goodies to itself.

Many of our clients refused to accept the concept of planting in spring or summer unless I offered a guarantee because they believed their sites got too dry over summer. They are now regular clients. One long-time tree planter of some ability in one of the toughest farm environments in Central Otago told me he liked to water the trees in their first year to guarantee survival but said “If I plant them in January I only have to water them for 2-3 months. Planted in August, I have to water for up to 7 months”.

This article by Graham Milligan appeared in the August 2000 issue of the New Zealand Tree Grower.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand