Blackwood – An overview

Ian Brown, New Zealand Tree Grower August 2006.

I think it is fair to say that blackwood, Acacia melanoxylon, has had a mixed press among tree growers. Since it was promoted as a species worth special attention by Forest Research in 1980, some excellent plantations have been established, and these should provide a good return to their owners. Other growers have been frustrated by blackwood’s need for good sites, and by its stubborn reluctance to grow straight without careful attention.

Over the last 25 years we have come a long way in understanding the species, its siting and silvicultural requirements. We now know how to grow blackwood with straight stems, and bring them to millable size within a competitive time frame. We have good reason to expect that blackwood timber will be sought after in the market.

Why grow blackwood?

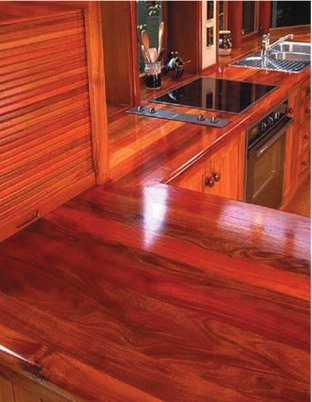

Quite simply blackwood is one of the world’s great decorative timbers, with a long history of acceptance in the international market place.

Growth rate in New Zealand is rapid, and in the view of Australian researchers, much faster than in Tasmania. Recent research from Ensis and from Tasmania has shown that fast growth does not compromise wood quality. Timber from fast growing blackwood in plantations has slightly higher density, and similar colour, to slower growing trees. A rotation of about 35 years is realistic, which compares well with other special purpose species and is not too far behind radiata pine.

Most farm foresters manage a portfolio of different species for interest and aesthetic reasons, and to cover their bets when marketing their timber. As the potential timber value is high, blackwood can be grown in difficult sites such as gullies which are unsuitable for livestock, and where poor access would make lower value alternatives unprofitable. Blackwood also fixes nitrogen, and with extensive roots deserves a wider role in stabilising hillsides.

Where to grow blackwood

There has been a growing recognition that blackwood is highly responsive to microsite conditions in both its growth rate and form.

It should therefore be regarded as site selective.

- It needs good shelter

- It grows best in warm locations, and is intolerant of heavy frosts.

- It needs reasonable moisture, and growth is inhibited by long dry summers.

It is therefore best planted on lower valley slopes, and moist gullies. Contrary to a common misconception it does not grow well in stagnant swamps.

How to grow blackwood

Form pruning

Unless the grower is committed to carry out early and regular form pruning until the future butt log is in place, there is no point in planting blackwood. Form pruning is simple, quick and easily learned. However to tree growers accustomed to radiata pine it will be unfamiliar.

The key points of form pruning are –

- Form pruning starts early, and must be done at least annually

- Pruning is at first directed to the upper part of the tree, rather than the base, and requires careful branch selection, while lower branches are retained

- Clearwood pruning should be delayed until at least year four

- On good sites, pruning is normally complete by year eight.

With attention to detail and a selection ratio of four to one, a straight butt log of five or six metres on final crop trees can be easily achieved.

Nurse crops and thinning

Blackwood can be inter-planted with nurse trees in an attempt to reduce troublesome branching, but unless carefully managed the nurse trees can cause their own set of problems. The trend in New Zealand has been to abandon mixed planting, and rely on form pruning.

A common mistake when growing blackwood is a reluctance to thin on time, an endemic failure among farm foresters. This can result in crown distortion and slow diameter growth. Current thinking is that we should aim for a final crop of about 200 stems per hectare.

What are the silvicultural costs?

Silvicultural costs can vary widely, depending on the management system that is used. While we have some provisional figures, this is an area that needs more work. The cost of form pruning, for example, depends on timing. It can be done very quickly with secateurs when the shoots are small. However it requires heavier tools a year later, and if delayed a further year or two will require considerable time and effort. If a nurse crop is used, this will demand additional time and expense.

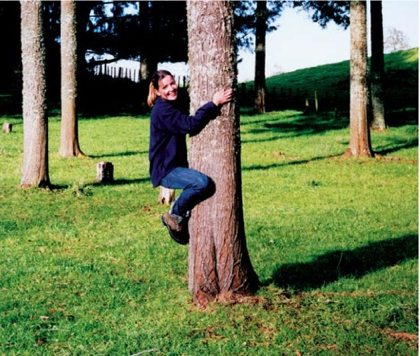

The current lack of certainty in costs and markets, the specific siting and silvicultural requirements along with innate conservatism, will probably continue to deter the corporates from growing blackwood. For private tree growers, who tend relatively small areas and do their own pruning, it is important to be aware of the management techniques and time required. However when pruning is done as a part time or leisure activity, as a pleasant and creative alternative to golf or a session in the gym, then the cost of pruning is not a consideration.

Insect pests

In Australia, blackwood is regarded as relatively biologically safe. This is in contrast to Acacia dealbata, which gets periodically hammered by the fireblight beetle. In New Zealand a number of insects have been associated with blackwood, and two of them are significant.

Acacia psyllids

The acacia psyllids have been recognised for a long time. They cluster around the new shoots in late spring and autumn, and by damaging the shoot tips bring seasonal growth to a premature close.

Psyllids contribute to malformation, but are not responsible for it. Malformation in blackwood is caused by abortion of the shoot tips which occurs when periods of growth are terminated. Control of psyllids will not prevent malformation, but can increase annual extension growth by up to 40% in young trees and is therefore a target worth aiming for.

Acacia tortoise beetle

The acacia tortoise beetle, Dicranosterna semipunctata, was first identified on a group of trees in Auckland about 10 years ago. As a strong flier, and prone to hitchhiking on vehicles, it has now spread to cover much of the North Island. It feeds actively on growing shoots, and can strip much of the new foliage off young trees. Reassuringly the older trees where it was first identified remain in good health.

Biological control of pests

Clearly it would be a great advantage to control both insects. A project that shows much promise involves the collection and release of the Cleobora ladybird, currently present in a localised area near Marlborough, where it was released about 25 years ago. Cleobora dines preferentially on acacia psyllids, and also consumes the eggs and larvae of the tortoise beetle. Both the eucalypt and AMIGO groups have received MAF Sustainable Farming Fund funding for propagation and release. Dean Satchell deserves much credit for initiating this project.

Blackwood as a weed?

A weed might be defined as a plant, or tree which spreads readily and grows where you do not want it. There has been some concern that blackwood might become invasive. In South Africa, where blackwood is highly valued for its timber, it can occupy disturbed sites and appear around forest margins. There it is classified as a weed, together with many other tree species. These include radiata pine and our own iconic pohutukawa, which has spread aggressively in shrublands near Capetown and which is subject to an energetic extermination campaign.

In South Africa, blackwood does not invade closed canopy forests because of its limited shade tolerance. Neither does it do so in the Tasmanian rain forests, and several reviews have shown that it is not invasive in our own native forests. On the other hand its seeds have longevity and are likely to germinate after disturbances in sites where blackwood have grown. More commonly in sites previously occupied by blackwood, saplings result from root disturbance. In contrast to South Africa it does not spread along river margins in New Zealand, the seeds are not transferred by birds, and many of the seeds are consumed by parasites. As a potential weed in New Zealand blackwood has low status, about the same as radiata pine.

We have worse examples including other acacias, some of the pines, and regrettably Douglas fir.

Markets

If the first principle of marketing is to have a product that people will want to buy, then blackwood is a good option. Currently the demand for blackwood timber is increasing in New Zealand, and exceeds supply. It makes an ideal substitute for rimu, just as cypress does for kauri. The price for blackwood timber paid by furniture manufacturers is now on a par with rimu, and is well ahead of other locally grown exotic timbers.

Offshore prospects also look good. Blackwood has had high status internationally for over 100 years. In China, blackwood has been targeted as a species for planting. It matches closely the timbers that have been used for centuries in high quality traditional Chinese furniture. Recently a series of large provenance studies have been undertaken in south east China, and extensive plantings will follow.

From the grower’s perspective, the selling and marketing of blackwood has been a haphazard business. Among the small scale contractors with portable mills there are some very good operators. There are also some cowboys.

There are of course practical difficulties. The trees are often scattered, present in small numbers and have poor access. Most have been untended, with resultant poor form and consequently a low conversion. Most of the larger mills have little experience of the special requirements in drying and sawing blackwood, and the end use sales are uncoordinated. Stumpage rates therefore tend to be very conservative in relation to the value of the final product. Much of this should change in future.

Development of markets and marketing

Significant plantings of blackwood, as well as cypress and eucalypts, have occurred since about 1980. These trees will be ready for milling in about 10 years time. In contrast to earlier plantings many of these have been well tended, and are located in woodlots that offer economies of scale. If we are to maximise the value from these trees it seems to me that we will in future need to take a more active involvement in their harvesting, milling and marketing. This could involve –

- Coordination between the NZFFA’s special interest groups

- Engagement with an agent experienced in harvesting and marketing

- Cooperation with a small number of strategically located mills where there is expertise in the special techniques required in handling these timbers They would need to be assured of a consistent supply and quality

- An active part in marketing the product.

All of this will involve herding some very independent-minded cats. However I think these are matters to which we should direct some thought over the next few years.

Other acacias

Among over 1000 species of acacia, there may be others worth looking at, for example by trialling some of the tropical acacias in warm northern areas. But currently, on sites that suit it, blackwood remains the best option.

There has been some interest locally in silver wattle, Acacia dealbata. This has widespread distribution in Tasmania and south east Australia, where it has attracted little interest, largely because of its high mortality and variable form. Although not on a par with blackwood, its timber can be attractive, and I have seen some very decent furniture in Australian showrooms, marketed as silver wattle.

Dead knots are a problem, so it would need aggressive pruning. Silver wattle has the advantage of very fast growth, and tolerates sites that are too dry and exposed for blackwood. It is certainly more invasive, a feature shared by some of the other acacias.

Ian Brown is a member of the Waikato Branch, chairman of AMIGO, the NZFFA’s blackwood special interest group, and co-author of Blackwood: A handbook for growers and end users. Forest Research Bulletin 225, 2002.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand