Clean water and carbon credits: How to get the most from fencing streams

Roger May, New Zealand Tree Grower August 2016.

Earlier this year the Ministry for the Environment published the consultation document Next Steps for Freshwater. Submissions on this closed on 22 April. This is part of the continuing process to develop the National Policy Statement on Freshwater Management, first notified in 2011, and the National Objectives Framework for freshwater introduced in 2014.

The Next Steps for Freshwater contains a number of proposals including two of critical importance to farmers. The first is a proposal to create a national regulation to exclude stock from water bodies − streams, rivers, and lakes. It covers dairy, beef, deer and pig farming and includes a timetable for implementation. Sheep and goat farming are not included.

Despite the fact that stock often enter water bodies while grazing on slopes over 15°, the proposal excludes these slopes for all these farm types. In addition, it is not clear how areas of sloping land are to be measured and identified.

Nevertheless, under the proposals farmers will be required to fence water bodies unless there is a natural barrier preventing stock from getting to the water. The regulations will apply to natural wetlands as well as permanently flowing waterways and drains greater than a metre wide and 30 centimetres deep. It excludes damp gully heads, places of temporary ponding, or built structures such as effluent ponds, reservoirs or channels. Although not stated, it is assumed here that the regulations will also apply to lakes.

No riparian buffers

The second important proposal is that no riparian buffers, the streamside margins between the fence and the waterway, will be required. While this may be a liberal policy, it is actually unrealistic and impractical. Fence posts cannot be driven in right next to the waterway and fence lines cannot strictly follow the path of a stream or other water body. For a range of practical reasons, such a fence needs to be at some distance from the water.

But many land owners may resent the cost and effort of fencing these water bodies and the seeming loss of productive land. However, there are solutions which could go a long way to easing these two hurdles and improve water quality at the same time.

Planting the margins

The most beneficial solution is to increase the width of the fenced riparian margin on both sides of a stream and plant the enclosed area with high value timber trees. By designing the fencing so that the average width of the future tree canopy is at least 30 metres, that is about 20 metres between the fences, all those trees would be eligible to earn carbon credits. If the right choice of species is made, these trees would stabilise the streambanks, reduce erosion, retain some of the overland soil erosion, shade the waterway and reduce water temperatures, and ultimately provide a valuable timber resource.

There is a wide range of special purpose timber species that are suitable for such a planting but the best choice, especially for earning carbon credits, are the exotic hardwoods. Farmers with a greater conservation impulse may also under-plant the main planting with longer-term native shrub and tree species.

| Farm type | Plains with slope from 0° - 3° | Lowland rolling land from 4° - 15° |

|---|---|---|

| Dairy cattle on milking platform | 1 July 2017 | |

| Dairy support owned by dairy farmer | 2020 | |

| Dairy support third party grazing | 2025 | |

| Beef | 2025 | 2030 |

| Deer | 2025 | 2030 |

| Pigs | 1 July 2017 | |

Rising price

Last year the government closed the loophole allowing carbon emitters to buy cheap credits from overseas and since then, the price of a New Zealand Unit has been regaining lost value. At 18 July the price was $17.90 a tonne, up from less than $2 in mid-2013, and predicted to increase even further.

Joining the Emissions Trading Scheme is voluntary but land owners with eligible trees planted after 1989 need to join in order to receive carbon credits from their growing trees. Different tree species sequester or absorb carbon at different rates. For those with less than 100 hectares in the Emissions Trading Scheme, the Ministry for Primary Industries has a set of five tables for calculating the sequestered carbon

- Radiata by region

- Douglas fir

- Other exotic softwoods such as macrocarpa

- Other exotic hardwoods such as oak or eucalypts

- Indigenous or native.

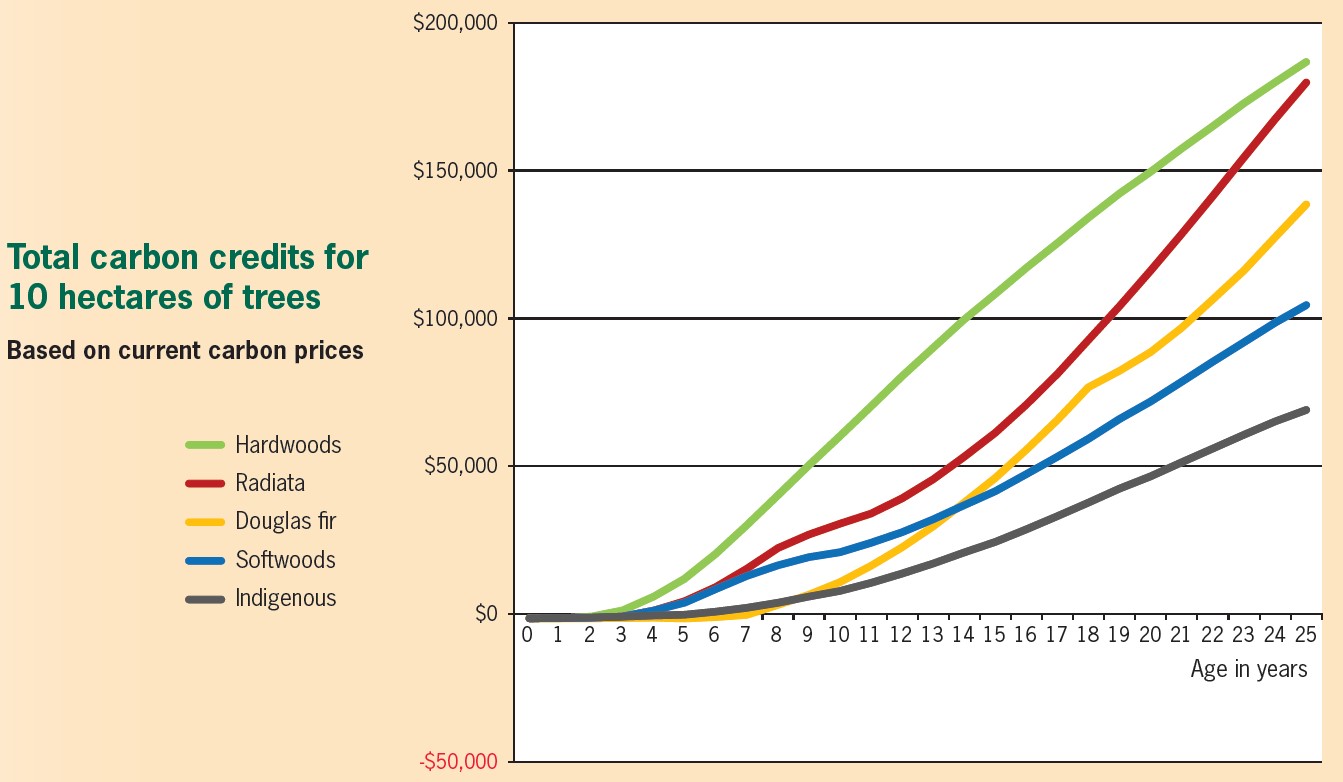

The graph above is based on these five tables showing the total value of credits for 10 hectares of trees up to 25 years after planting. It is based on today’s carbon price and, conservatively, increasing at a dollar a tonne each year. The calculations do not include the costs of land preparation, seedlings or planting but do take account of the costs associated with joining the Emissions Trading Scheme and lodging all mandatory carbon credit returns.

While carbon credits have to be repaid on harvested trees, these liabilities can be minimised by spreading the initial planting, the harvesting and the replanting over a number of years. This method is more likely to be economically feasible with higher value timber trees such as the hardwoods and some special-purpose softwoods.

Roger May, Tomorrows Forests Ltd on info@tomorrowsforests.co.nz

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand