Selling standing trees and forest land

Kim von Lanthen, New Zealand Tree Grower August 2017.

If we think of a woodlot as an asset, then it has a market value. For woodlot owners wanting to cash out before harvest, there are two important questions. Can I sell a woodlot as a standing crop? and will I get a fair price? The answers are, yes and maybe. It depends on how well you prepare for the sale. People love certainty, and will pay more if they know what they are getting.

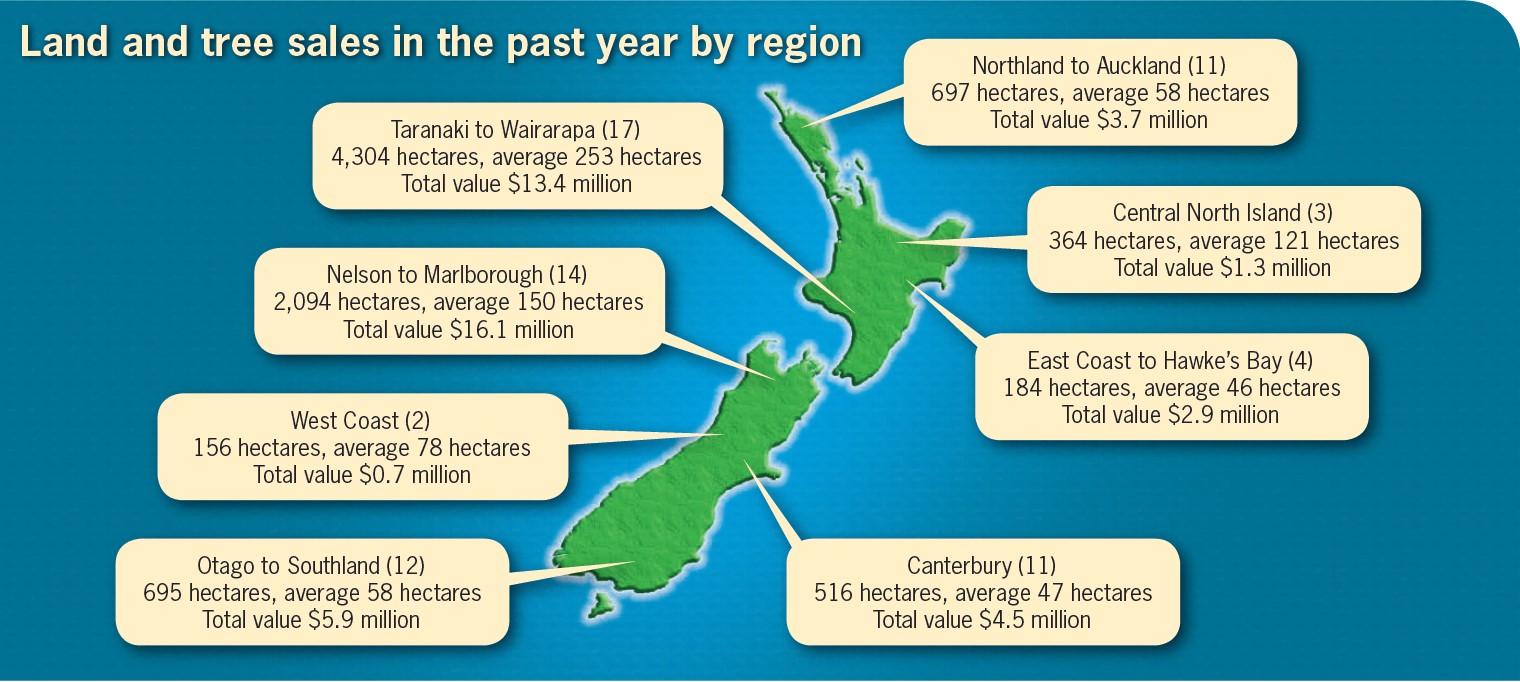

Most sales of woodlots involve both land and trees. Over the last year, the Real Estate Institute recorded sales of 9,010 hectares of woodlots for a total of $49 million. Most transactions were at the bottom of the North Island and top of the South Island. The size of the blocks varied from four to 1,121 hectares, with an average of 120 hectares. The predominant method of sale was private negotiated treaty, with a few blocks sold by tender.

Unfortunately, the Real Estate Institute does not provide detail beyond the number of hectares sold, the method of sale and the total sale price. You cannot draw many conclusions from this.

The speciality forest exchange ForestX which has been trading since August last year, has completed 24 sales in its first few months. As a platform for buying and selling forests, it tracks all forms of sales from start to finish The emerging picture from the exchange suggests that quite a detailed analysis will be possible in the future as it builds its transaction base.

Paired samples

The 24 transactions to June include sales across all age classes of trees, and of several plantation species. There have been two sets of sales in close proximity to one another that allow close examination of paired samples to show what has been happening in the market.

The first pair was sold in Canterbury. Both forests were established in the early 1990s with similar access to processing and ports. One forest sold for more than the capital value of the land, the other sold for less. That is, in one sale the buyer wanted the trees and paid for them, and in the other the buyer saw them as a problem. The first vendor carefully described the trees being sold and their silvicultural history. The second vendor was less specific in describing them.

The second paired sample was in Otago. Both blocks were planted in the same year, with similar access to processing and ports. The blocks were of different sizes but the owner of the smaller block received 13 times more for his trees in dollars per hectare than the owner of the larger block. Again, the block with better information on the trees produced the better value.

You could argue that these price differences might be due to differences in the quality of trees or harvesting access, but the extent of the differences cannot be explained by these characteristics alone. The quality of the information presented by the vendors appears to have had a bearing.

Preparing for sale

This conclusion might be premature and will be tested as we build transaction history. It is logical to suggest that any vendor should carefully prepare for a sale and offer a comprehensive description of the asset in advertising.

What should this comprehensive description contain? Effective advertising should cover the main reasons for the value. These include the physical characteristics of the forest with a full and honest description of what is being sold, and what it might earn using a frank assessment of costs and revenues into the future. Other value includes the likely risks the buyer will consider over matters such as resource consents and log prices.

Some information is common across all forests and need to be collated right at the outset.

- Location including road name and number with a map of the forest boundaries

- Resource including stocked area, species with genetic improvement if possible, the year planted, stocking, slope and any current roading

- Management regime – pruning, thinning, for carbon

- General health and vigour

- Site including distance from public road, access points and vehicle access

- Wood volume with total standing volume estimates.

Buyers will try to assess the net cash flow the forest will generate and sellers need to be ready to substantiate any figures they offer. Main questions relate to −

- Cash in the log markets, carbon and ancillary crop income

- Cash out including maintenance and other outgoings such as ground rent, rates and insurance, roading and harvesting options

Taxation

Income tax is also important. A vendor must pay tax on income from the sale of standing trees, but a buyer cannot deduct the expense until such time as the trees are harvested or sold again. This mismatch in the timing of the tax liability and the tax credit can mean that the buyer will offer less for the trees than the vendor expects. The effect is greatest with young trees and least with mature ones because it relates to the time the buyer must wait to claim his tax credit.

When preparing for a sale it is important you understand these concepts, and the risks that the buyer will consider. These are likely to include −

- Market risks outlining local market demand, distance to market, presence of alternative land uses along with availability and terms of finance

- Regulatory risks showing the availability and terms of resource consents, changes to carbon regulations and tax changes.

If the vendor is selling only the standing crop, he may offer the buyer a forestry right. Included in the agreement often as a joint venture are the terms of access, harvest, roading improvements and any clean up.

Take courage, woodlots are selling. But there are indications that the price you receive will be influenced by the efforts you make in drawing together accurate and comprehensive information on what is being sold. It could also be enhanced by the sales strategy you deploy, if you can add competitive tension by interesting several parties in bidding for the block.

Kim von Lanthen runs Commodity Markets (NZ) Ltd, www.forestx.co.nz

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand