Forestry lifestyle blocks: Subdivision opportunities and pitfalls for sellers and buyers

Hamish Levack, New Zealand Tree Grower August 2020.

Subdividing a rural property is a complex process and you will probably have to jump through a number of hoops to succeed. Although district and regional councils provide useful guidelines for rural subdivisions, you will need specialist help. It is advisable from the outset to engage a firm which assesses the feasibility of your ideas, designs the subdivision layout, prepares resource consent applications, carries out all the surveying and engineering work required, coordinates the installation of new services and project manages the entire process.

However, such firms do not necessarily have expertise in forestry. If you want to establish trees it is advisable that, quite early in the process, you consult someone who is familiar with forestry. These days many local authorities require a forestry management plan which takes into consideration planting and how the eventual harvesting will be carried out.

A hill country farm being subdivided

In 1975 five friends, including Sir Godfrey Bowen the world champion shearer, had collectively made some money on the back of their success as a team of New Zealand’s top demonstration shearers. They bought 250 hectares of reverting hill country farmland alongside Otaki Gorge Road, on the Kapiti coast north of Wellington.

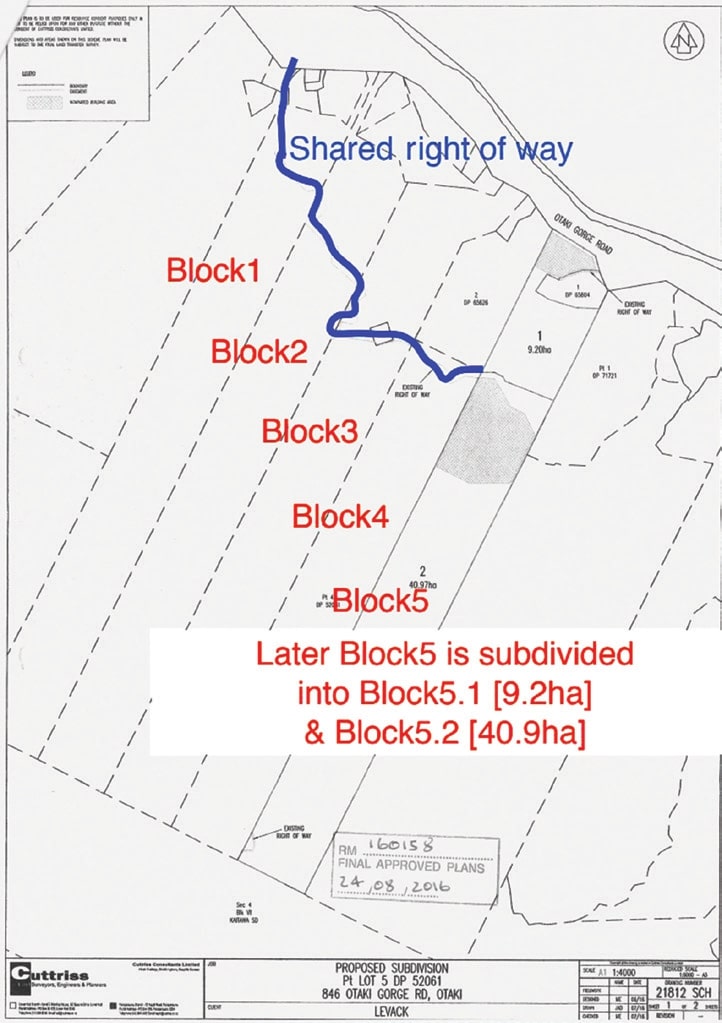

They subdivided it into five 50-hectare blocks so that each person would own one block. Common access was by a farm road, or right of way, which they had surveyed and registered against each of the five titles. They then had the land planted with radiata pine with the help of a Forest Service grant. The result was five afforested lifestyle blocks, each about 50 hectares in area, just an hour’s drive away from Wellington, which had been created out of land no longer profitable for sheep farming.

The combined land value of the five blocks, less the cost of creating them, was immediately worth more than the value of the un-subdivided 250 hectares. As expected, the continued urban expansion on the Kapiti coast meant that the block values kept increasing.

Some of the pitfalls

Just after 1989, when I bought block five, all the original investors who by then were either well into retirement or dead, had cashed up. At this stage problems arose with the right of way, marked in blue on the map, which provided common access from the Otaki Gorge Road. The whole forest was overdue for thinning to waste and the new proprietor of blocks one and two let numerous large tree stems fall across the right of way while carrying out his thinning. I complained that the access to the middle of my block had been obstructed, and more importantly, pointed out that the local rural fire service would not be able to get their vehicle in to extinguish a fire should one start.

The owner countered this with the argument that the felled trees stopped trespassers who would be the likely cause of any fire. Of course his real reason was that he did not want to be bothered with clearing the right of way. I could have taken legal action to make him remove the obstructions, but the cost of pursuing this would not have been worth it. I happened to have adequate alternative access to my block from Otaki Gorge Road, although knew that the right of way would have to be cleared when harvesting began. The easiest way to do was to ignore the matter, albiet with feelings of indignation.

Road construction for harvesting

The harvest of all the blocks took place during 2002 and 2003, and as expected it involved the construction of a road to take out logging trucks, more or less along the line of the right of way. However, part of the surveyed right of way over block two was unsuitable for logging trucks. Road realignment outside the surveyed right of way to create an acceptable gradient and turning configuration was needed for heavy vehicles.

Conscious that this could cause legal problems later, I agreed to allow the deviation if the owner agreed to share the cost of re-surveying and re-registering the right of way on the titles. He accepted this condition in writing. After pocketing the income from his harvested trees, he sold his two blocks and decamped to Australia. Because the written agreement had not been registered on his titles, the new proprietors were not bound by it.

I had initiated the re-survey so I ended up having to pay for it. This was a waste of money because the new proprietors of blocks one and two saw no advantage in letting the revised right of way be registered on their titles. This business is still incomplete, and a source of future legal disputes among the block owners.

After the trees had been harvested, the skid sites on blocks one and two, which had good views of the Tasman Sea, became attractive platforms for building houses. Once these smart houses had been built, the new owners wanted to upgrade the right of way through their blocks. This gave rise to further difficulties in getting the owners of all the blocks to agree to the standard to which the new right of way should be kept, and getting the users of the right of way to agree to pay what each thought was a fair share of the maintenance.

More on rights of way

Another forest owner, Jason Lisette, provided two similar examples of rights of way that he had been involved with. The first consisted of a forest which spanned 12 titles, half of which had public road frontage access, but all of which were parties to a right of way. Dissent was generated when it was realised that each owner had to pay an equal share of the right of way upgrade even though those who had the road frontage blocks did not need this for harvesting.

The second example was a 36-lot subdivision. In this case, even though each block had been planted during the same winter, wood quantity and quality varied greatly because of differences in management and topography. This led to disagreements about when to harvest, who the logging contractor should be, and what and when individual contributions towards the right of way upgrade should be made.

The lessons to be learned

Creating and changing easements on rural land can be costly and complex. Easements can apply to setting up rights to convey and drain water, to drain sewage, to convey electricity, telecommunications, broadband and gas. But the most common sort of easement in forestry is a right of way.

Although a shared right of way implies the advantage of shared costs of road construction and maintenance, it is a common cause of neighbours falling out with each other. If you purchase land which involves a right of way, think about future harvest operations and try to ensure that there is a process registered on the relevant titles to cope with the decisions needed about upgrading part or all of the right of way and how that should affect shared costs. Beware that, although a rural right of way may be adequate for light vehicles, it may not be suitable for the heavy vehicles needed when a forest is harvested.

At the outset, as with Godfrey Bowen and his friends, you may feel confident that you can trust the others involved with a shared right of way. But sooner or later these friends will be replaced by newcomers who will probably not have the same values or sense of mutual obligation. If a person benefitting from the right of way refuses to share in its maintenance, or decides to over-use it, legal compliance may be possible but not worth pursuing.

Forest land subdivision can be profitable

The land I bought, block five, excluding the tree crop, cost $84,000 in 1989. Adjusted for general inflation this comes to $156,000 in 2017. In spite of the right of way problem, it was independently valued in 2017 at $275,000. That makes it a real, adjusted for inflation tax-free return on investment of two per cent a year.

However, in 2017 block five was further subdivided, and after paying for the associated surveying, district council consents and legal fees of about $40,000, they were sold for $380,000 instead of $275,000. This meant that subdividing provided an additional real tax-free return of 38 per cent during 2017.

This is quite satisfactory when you consider that the forest on the land was also generating a taxable profit of about seven per cent a year since 1989. Substantial intangible benefits were additional. An area such as block five provides space, views, privacy and that country feel. It is somewhere to indulge in the Japanese beneficial therapy of shinrin yoku, or forest bathing. It also means tax deductions on things that maybe you always wanted to buy, such as a caravan, a four-wheel drive vehicle, a chain saw or a generator. In short, a block like this is a paradise get-away for Wellington urban dwellers.

Beware of the Bright line test

Those of you who are now interested in buying a small hill country farm with a view to perhaps planting it up, but selling off the homestead and a few hectares of flat land as a life style block to someone else, you need to beware of the government’s Bright line test. The government introduced this a few years ago to discourage quick property speculation. If the subdivided property is sold within five years of purchase, then the nett profit is taxable.

Minimising future problems with neighbours

When you come to harvesting your woodlot, beware of friction from your lifestyle block neighbours, especially those who are grazing sheep, cattle or horses and are uninterested in trees. An application for a resource consent to fell trees may result in the relevant council seeking the views of neighbours or people affected by the activity. If the council decides to notify the application, then the forestry operation under scrutiny is thrust into the public eye and the associated processes can become very demanding and expensive.

This will be frustrating to a forest owner who is used to his forestry operations being uninterrupted long before the lifestyle block neighbour turned up. The forest owner’s frustration will probably be reinforced if they were responsible for creating the lifestyle block owned by the problem neighbour.

Planning ahead

It is not unusual for a hill country farm to be bought with a view to subdividing the flat land as one or more lifestyle blocks and afforesting the rest. Therefore, if you plan to subdivide, consider insisting that the purchaser of the life-style block, who is to become your neighbour, agrees to complaints covenants being registered on the title. These covenants can be tailored to your situation but could, for example, provide that the purchaser, including future owners and occupiers of the property −

- Cannot build dwelling houses or other structures within a certain distance of the boundary of the forest owner’s land or from roads used by the forest owner

- Will allow the forest owner to carry out on its land all forestry activities associated with a normal commercial forest

- Will not make any claim, take any proceedings or support any action arising out of the forest owner’s forestry activities

- Will not further subdivide their property

- Agrees to any resource consent application required for the forest owner’s forestry operations.

This is, of course, a bit of a balancing act. The more constraining the covenants are, the less you as seller are likely to get for the sale of the lifestyle block. The last two provisos are could prove the most difficult to get the purchaser to agree to They will probably realise that the marketability of the lifestyle block could be diminished later.

Hamish Levack is a small-scale forest owner and President of NZFFA.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand