Where blackwoods go wrong

Ian Brown, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2005.

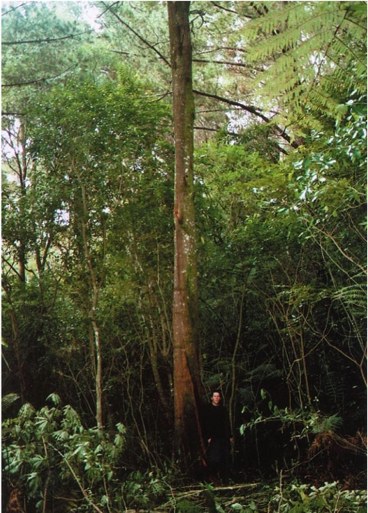

The photograph at the bottom of the page is of a blackwood which we planted in 1980 in the Far North. At 24 years, its diameter is over 50 cm, and it is nine metres to the first branch. It is of course one of our best trees – no one shows off their failures. However, although clearly selected it does indicate the potential for blackwood growth. On an adjacent trial plot the mean top DBH at the same age is just over 50 cm, with a trajectory that suggests this will reach 60 cm before 35 years.

Good in patches

Our forest, in which we planted over 8,000 blackwoods, is a typical farm forester’s curate’s egg – good in patches, not so good in others. This may not be a bad thing. The familiar mix of good and bad provides those of us who are amateurs in a field dominated by professionals with a special advantage – by making more mistakes we get on to a fast learning curve. In my case the mistakes have been mainly errors of omission. Because of the distance from home, which meant infrequent visits, and various distractions when we got there, the work never got quite finished. As a learning experience this was perhaps fortunate in that it provided a comparison of treated and untreated trees. It was in effect a farm forester’s version of a controlled trial, in which the number of the control, or untreated trees was determined by the demands of the family, and by the quality of fishing nearby.

After looking critically at these trees over time, and at the efforts of other blackwood growers, it is clear to me that we all make the same mistakes. It is not difficult to grow good blackwoods, but there are a few fundamental areas that need attention if we are to grow them successfully.

Survival and performance

Blackwoods will grow almost anywhere in New Zealand. In Australia, where they mix with some pretty tough competitor species, they have a wide natural range. This has led growers at times to plant them in inhospitable sites, where they have conspicuously failed to thrive.

If we are to make a profit from these trees we should make a clear distinction between survival and performance. In blackwood, more than most of the trees we grow, performance is greatly influenced by site factors.

If we are to make a profit from these trees we should make a clear distinction between survival and performance. In blackwood, more than most of the trees we grow, performance is greatly influenced by site factors.

For a species with a reputation for toughness, blackwoods are surprisingly demanding. On dry exposed locations they are generally slow growing, with a short trunk and disorderly branch architecture. They do not tolerate heavy frosts. They grow best in warm areas. Of particular note is that, although they respond well to moisture, they do not tolerate waterlogged soils. This may surprise some growers who know that the Blackwood Swamps of north west Tasmania produce most of the commercial crop.

The Blackwood Swamps are in fact river floodplains, and are dry underfoot for much of the year. Blackwoods are dominant there as they will tolerate occasional flooding, provided the water is flowing and oxygenated. This is quite different from our version of a swamp, in which the water is stagnant and never dries out. When planted in such conditions blackwoods are unlikely to survive.

Blackwoods like decent, well-drained soils, need good shelter, and respond to warmth and plenty of moisture. Ideal sites are gullies and lower valley slopes. They are therefore best suited to mixed plantings where more exposed sites are occupied by other species.

To get the best from them blackwoods should be regarded as highly site selective.

Pruning

The worst thing that can be done with blackwoods is to neglect to prune them, and simply plant and hope for the best. The inevitable outcome is the blackwood we all know, with a bole too short to be useful, and massive branches. Almost as bad is to leave them a few years, and then call in a commercial gang. They will prune them like radiata, and convert a shambles into a disaster.

Programmed to frustrate tree growers

Blackwoods are genetically programmed to frustrate tree growers. As they grow they periodically abort their leading shoot tip, and later replace it with lower branches, which then tend to form double or multiple leaders. This may suit the biological interests of the tree, but not the commercial interest of the grower. Although most conspicuous in open grown trees, malformation also occurs when blackwoods are grown in mixtures. Growing blackwood in mixtures, although theoretically appealing, is not as easy as it might seem in practice.

Malformation in blackwood is something we have to confront, and I do not believe we will solve the problem by tree selection.

Learning a few tricks

This means that we have to use a system of form pruning aimed at producing a straight stem of about five or six metres in length.

The basic concept is easy – it is simply a matter of selecting and removing competing leaders. There are a few tricks which can be quickly learnt.

The branches to be removed can be selected either visually, or by measurement using a gauge. Form pruning can be done quickly, and with little effort. The first three metres require no more than a few visits with a pair of secateurs. This is not difficult to learn for growers with no forestry experience. However the method is unfamiliar to growers who have spent some time pruning radiata pine.

The best results

To get the best results from form pruning there are a few basic rules:

- Start pruning early, preferably no later than the second summer

- Form prune once a year – the best time is probably late spring

- Aim for a straight stem of five or six metres, but a shorter stem of good diameter will be very acceptable.

- Follow through with clearwood pruning, which usually starts at about year four.

- Remove any branches over three centimetres.

The key message is that unless the grower is able and prepared to carry out regular form pruning, it is a waste of time to plant blackwoods.

Thinning

Farm foresters generally make a good job of establishing and tending their trees. The price we pay is that, in doing so, we become too fond of them, and are then reluctant to thin on time. For some species a delay in thinning may not matter too much. With blackwood it certainly does matter, and the effect is dramatic.

A common mistake

When blackwood crowns come into contact, the live crown can retreat with disconcerting speed, often within a year or two, resulting in a small high crown. The effect of this is a marked slowing in the rate of diameter growth, and a much longer rotation. This is one of the most common mistakes in growing blackwood. Good examples can be seen on many woodlots, and wherever blackwoods have been planted by city or regional councils. On reasonable sites, thinning should start when the crowns begin to compete at about year six, and be complete before year 10, leaving about 200 stems per hectare.

Reluctance to thin is understandable. It means sacrificing some very good trees, and the remaining trees, which are about seven or eight metres apart, can look very lonely. But it has to be done. If you are squeamish about thinning, employ a steely-eyed contractor to do it, take a holiday, and come back when it is all over. Blackwood millers like fat trees. To grow them fat they must be thinned on time.

Great potential

In summary, when growing blackwood and having selected a suitable site, the first principle is to prune on time, and the second is to thin on time. There is of course more to it. Over the last 20 years a lot of good information has emerged, mainly as a result of excellent research trials carried out by Ian Nicholas and Ham Gifford of Forest Research, together with much anecdotal experience by farm foresters.

We now have enough knowledge to consistently grow high quality blackwood trees, and the AMIGO group is happy to share it. There is no need to repeat the mistakes of the past. As a species that will deliver high quality decorative timber for a niche market place, blackwood has great potential.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand