Macrocarpa – keeping faith with the old faithful

Denis Hocking, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2006.

In the first part of this issue of Tree Grower we are featuring articles covering some of the varying species and clones of cypress. The main generic name is Cupressus, and if we were to be accurate, the full species name should be used such as Cupressus macrocarpa or C. lusitanica. However most of us generally refer to the different commonly known cypress just by their species name such as macrocarpa and lusitanica. To make reading the articles easier, and to avoid excessive use of Latin and italics, this is the style that is used throughout the feature. However Latin names are used where it seems necessary to do so.

Has good old macrocarpa been unjustifiably maligned in recent discussions? An old faithful sent off to the knackers ahead of its time? I am inclined to think so. After all macrocarpa – the name is usually shortened to this one word – was the species that introduced and educated New Zealanders to the virtues of cypress timbers, only to be condemned by cypress canker in recent years. But are the problems with cypress canker perhaps due as much to our misplacement and mismanagement of the species as to its terminal failings?

Relic of an earlier era

Macrocarpa is a relic of an earlier era and colder ice age climate it hung on by its root hairs on just 70 hectares on the foreshore of the Monterey peninsula. Obviously the climate and conditions of modern day Monterey do not really suit the species. If they did it would be much more widely distributed. It is more likely that it has survived down on the beach because of one notable attribute, tolerance of high levels of salt wind and spray.

Despite its tiny natural range, it has been found to be genetically quite diverse. This, along with the fact that there are a number of closely related cypress species dotted throughout California on very small natural ranges, suggest that Cupressus was once a much more dominant genus in present day California, perhaps during the colder climate of the last ice age. Of course lusitanica and C. arizonica are still widely distributed in higher country to the east and south along with Chamaecyparis spp. to the north.

So is it just possible that with appropriate selection from within this genetic diversity and planting on cooler sites, macrocarpa might continue to be a desirable plantation species for farm foresters, and even foresters. What are the strengths and weaknesses of this species?

Strengths

- Very good quality timber, stable, with attractive appearance, good working properties and significant natural durability. Even if technically other cypress species may match it, macrocarpa remains the local industry standard and market preference.

- It has relatively low and consistent sapwood content, typically five growth rings compared to 7 to 14 with lusitanica.

- Fast growth and the potential to grow to very large diameters. There are plenty of trees that have shown average annual diameter increments of three centimetres for periods of 15 or 20 years.

- Macrocarpa responds well to silvicultural treatment with good diameter responses to thinning, even if these are a little less dramatic than with radiata pine.

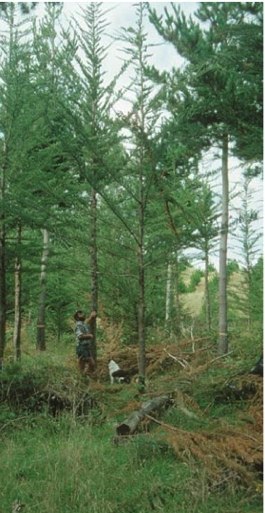

- Responds well to pruning, including very hard pruning, and it is easy to produce clearwood.

- Reasonably site tolerant, with excellent tolerance to extreme salt wind, even salt spray, and good tolerance to shade.

- Surprisingly genetically diverse.

Weaknesses

- Susceptible to cypress canker.

- Tends to produce larger numbers of branches and larger branches than other cypresses which makes for more expensive pruning.

- Often produces heavily fluted logs, especially lower logs. Both genetic and environmental influences appear to contribute to fluting.

- Needs more fertile soils than radiata pine and some of the eucalypts, therefore macrocarpa grows very poorly on steeper sand dunes, but acceptably on the flats.

So the question is – how do we maximise the strengths and minimise the weaknesses of macrocarpa? As in all forestry, we have three tricks in the tool box – environment or site preference, genetics and silviculture.

Site preferences

So let us start with site preference. It seems to have been common knowledge for many years that the healthiest and best formed macrocarpa are almost always on cooler, shadier and sheltered sites, be it trees on a southern slopes or understorey specimens, although there are exceptions. Mark Self made exactly these points in a very good article on cypress canker in the May 2003 Tree Grower, ‘Warm sites favour canker development … wind damage facilitates infection by canker fungi’. Apparently the canker fungi Seridium cardinale and S. unicorne have comparatively high optimal temperatures around 27°C. The worst canker is normally reserved for exposed, north facing slopes.

So put your macrocarpa on reasonably good soils, on cool sites, especially southern slopes. But bear in mind that sometimes things work better than expected on less than ideal sites.

Genetics

Select a good canker resistant clone or seedlot. I do not think that any commercially available seed lots offer any gains in canker resistance. There definitely seems to be marked differences in canker susceptibility between different clones and certain seed lots.

Kukupa was the first commercial clone released by Forest Research in 1992 and proved to be such perfect fungus fodder, it perhaps did much to educate people on the limiting influences of cypress canker, but probably did not do a great deal for the reputation of macrocarpa. In my limited experience, seedlots from Rodney Faulkner’s trees have probably performed best, but all I am really prepared to say is that there are marked differences in canker susceptibility. Getting hold of seedlings that can be confidently described as canker resistant may be quite a challenge. I think it would be worth putting more effort into wider surveys of macrocarpa plantations, looking for improved canker resistance, and even more important, trees producing canker resistant progeny. Progeny testing is of course, a much bigger task than just a simple survey, but Forest Research did develop lab tests to identify canker susceptibility in seedlings some years ago.

To date, all that has really been surveyed is the incidence of canker. I would also like to see a bit more survey work done on fluting to see whether we can tease out the significance of some of the factors here. But I would regard this as a lower priority than canker resistance.

Silviculture

Finally there is silviculture, which in my opinion is probably less significance for health and form, although there is some debate about this. I had always believed that pruning, even severe pruning, does not seem to be a major factor in canker susceptibility. Certainly there is no evidence that pruning aids infection and the direct spread of canker, but Patrick Milne is quite adamant that pruning does increase susceptibility to canker when the disease is already present in a stand. There is agreement that severely affected trees should be thinned out of a plantation to reduce the innoculum load.

A simple plea

So my plea is really quite simple. Faithful old macrocarpa has many virtues, along with a few quite serious problems. With care and attention I think we can reduce these problems to acceptable levels and continue to benefit from the virtues. Let us not give up on macrocarpa just yet.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand