Cost-benefit analysis of tree fodder

John Stantiall, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2008.

Analysing the financial benefits of using poplars and willows as fodder trees is a challenging exercise, due to the range of possible scenarios and different perceptions about which costs should be included. The range includes

- Poplar trees planted specifically for fodder or for erosion control, which are pollarded – the branches cut back to a stump above browsing level – for drought feed,

- Shrub willows which are grazed by sheep or cattle

- Shrub willows used for dairy effluent management.

Items often discussed with respect to inclusion in the analysis are the initial establishment costs, loss of grazing during establishment and labour. The analysis to date suggests that trees managed for fodder may only be cost-effective in some situations if the labour cost is not taken into account.

Any particular analysis is only valid for the set of circumstances being studied and the assumptions made. For the purposes of this project, the farm systems where the trial blocks were grown were initially modelled because recorded information was available. Based on this information and a set of assumptions, several similar options were developed to investigate the effect of variables, such as the percentage of effective farm area planted in trees.

The model could be developed to the stage where farmers could use their own information and test the economic benefits of planting trees for fodder or dairy effluent disposal on their own farm. The following results are tentative, and may be modified as new information becomes available or the method is refined.

Pollarded poplars

For a poplar block planted at 400 trees per hectare, if the trees are harvested every three years it is assumed that the pasture production is similar to a block without trees because a reasonable proportion of light still filters through to the pasture. Based on 2004 to 2005 prices, the cost of establishing a pollarded poplar block is about $3,140 per hectare, or $1,680 if labour costs are not included.

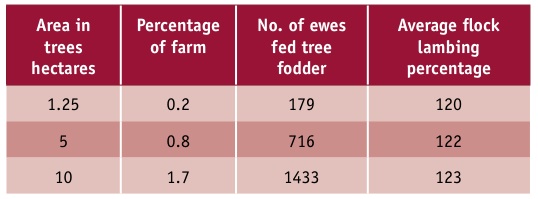

The model is based on the availability of edible dry matter, and assumptions made based on farmer experience about the difference in lambing percentages for the ewe flock and stock sale weights. Farmer experience indicates that ewes fed tree fodder have an increased lambing percentage of 3% to 5% compared with the others during a drought. Therefore for the whole flock, the effect on lambing percentage will depend on the proportion of ewes that have access to the tree fodder. This is illustrated by the following example assuming –

- A pollarded poplar system

- Farm size of 600 hectares

- Flock size of 1750 ewes

- Tree fodder comprises 15 per cent of the ewe's diet

- 120 per cent lambing without any tree fodder

- 126 per cent lambing with tree fodder.

From this table, it can be seen that the effect of a small area of trees is diluted across the total flock. While the extra lambs provide extra income, this relativity only occurs in the drought years. The stock performance advantage for fodder trees only occurs in the drought years ? one year in five is used in the model. In the other four years, the farm with the trees has the same stock performance, but must continue to carry the extra costs.

The greater the area of trees, then the greater the costs that must be carried each year. Therefore in non-drought years, the farm operating surplus is decreased by the cost associated with having the trees. Based on current costs and prices, for a 600 hectare Otago farm, up to four hectares, or 0.7 per cent of farm area of pollarded poplars is profitable if the labour costs are not included. On a North Island hill country farm where there is a higher sheep stocking rate, up to 2 per cent of the farm area in pollarded poplars may be profitable if labour costs are not included.

The greater the area of trees, then the greater the costs that must be carried each year. Therefore in non-drought years, the farm operating surplus is decreased by the cost associated with having the trees. Based on current costs and prices, for a 600 hectare Otago farm, up to four hectares, or 0.7 per cent of farm area of pollarded poplars is profitable if the labour costs are not included. On a North Island hill country farm where there is a higher sheep stocking rate, up to 2 per cent of the farm area in pollarded poplars may be profitable if labour costs are not included.

Browse willows for sheep grazing

The willow browse block was planted at 7,000 trees per hectare. Often an area is chosen which is constantly waterlogged, and produces very little pasture, especially during winter. The willows have the effect of drying the soil, allowing more pasture to grow and be grazed throughout the year.

This system can result in extra pasture production along with the tree biomass, compared with similar areas without trees. On this basis, extra stock are wintered on the browse block. The willow block has a high establishment cost of $9,870 per hectare including labour, $7,320 without due to the high plant population. There is also a loss of grazing during the establishment phase, but this is minimal due to the low initial pasture production.

For a 500 hectare Wairarapa case study farm, up to two hectares, 0.4 per cent of farm area, of browse willow was profitable if the labour costs were not counted. If the willow tree crop lasts only ten years, then the establishment costs double within a 20 year period, and each crop provides fodder for only two droughts. On this basis

alone, the crop would be unprofitable.

Willows for dairy effluent uptake and forage

For the case study property at Clydevale, Otago, willow cuttings were planted at 7,200 per hectare on 0.6 hectares and a K-line irrigation system was installed. The edible yield in February 2006 was about 0.35kg dry matter per tree from the trees planted as cuttings. At about 90 per cent tree survival, this equates to 2,268 kg dry matter per hectare for the first 18 months. It has been projected that once established, the annual growth of edible material will be about 1.8kg dry matter per tree or 11,664kg dry matter per hectare.

For the specific case study at Clydevale, the model produces a net benefit of over $372 per hectare of trees planted, or a benefit over the whole farm of over $0.93 per hectare. For a given situation, the relativity between the tree area and the farm size will have a big influence on the overall net benefit to the farming business.

These figures relate to the fodder value from the system and exclude benefits and costs from nutrient removal by the willows, or any other application of these trees on a farm.

John Stantiall is an agricultural consultant with Wilson & Keeling Ltd, Feilding. This article has been reprinted with permission from the booklet Growing Poplar and Willows on Farms compiled and prepared by the National Poplar and Willow Users Group.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand