Dairy run-offs

Gabrielle Walton, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2009.

Over the last 12 months 28% of farm sales in the Bay of Plenty have been to some form of dairy runoff use. The reasons for purchasing a dairy runoff are varied and include control of winter grazing and animal health, the price of off-farm grazing, growing feed and selling surplus feed, young stock grazing and land banking.

The land being sought for runoffs shows consistent attributes. Generally it is easy to medium hill country with some flat land for hay, silage or crops, good grass growth, not too high, good aspect, ample water supply and easy distance to the milking property. Remember these are flat-land farmers moving into the hills.

Farm forestry involved

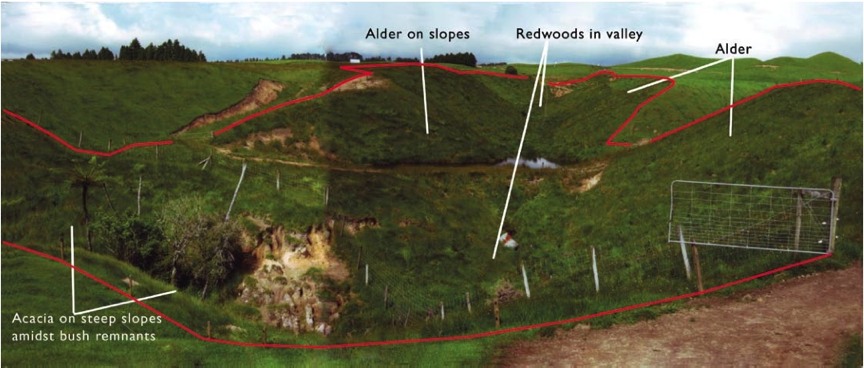

Unfortunately the hills also have varied landform, valleys turning into gullies, steep sidlings often prone to erosion, springs and faster flowing waterways, and wind. At $1,500 a head no dairy farmer wants to lose a cow in a creek or see a heifer break a leg on a steep sidling. These awkward areas are best taken out of the picture, and that is where farm forestry can help.

In February 2008 I was asked by the Hickson family, dairy and kiwifruit farmers from Pongakawa, to help them with plantings on their newly acquired dairy run-off in the hills behind Te Puke. The Hicksons have a dairy herd of 750 cows. When prices started reaching $20 to $25 a cow for a week for winter grazing, and imported feed crept up in price, the decision was made to buy a runoff block in the nearby hills.

The farm

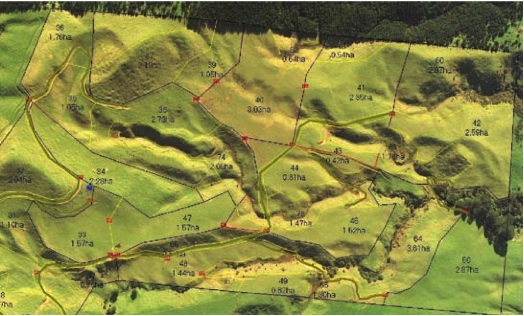

The property is 115 hectares, an ex-deer farm on rolling hill country with flat land and broad easy valleys that form into incised gullies. It has a north to north-east orientation at 300 metres, is reasonably sheltered from north west winds, has loamy soils with erosion potential on steeper slopes and rainfall in excess of 1,600 mm a year.

The large deer paddocks were divided into smaller areas and along with improved water reticulation, easy all-weather tracks were installed with good culverts and well designed runoff. Erosion from deer tracking along fence lines was bulldozed and grassed where the land was not too steep.

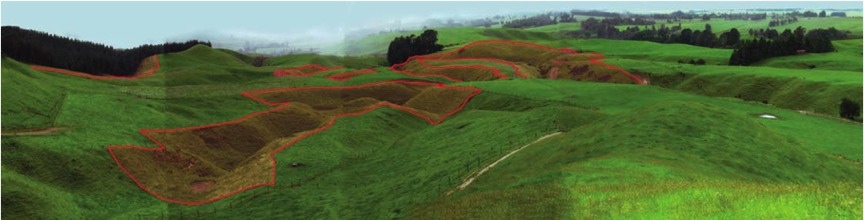

The decision was made to fence off 15 hectares of incised gullies and waterways to avoid stock loss and remove stock from waterways. Planting of these areas was necessary to reduce weeds, provide shelter to adjoining paddocks and improve the farm’s appearance and value.

Blending into the environment

In taking on this project as a landscape architect my major focus was to ensure that any changes to the landscape would blend into the local environment. I had to work on issues of loss in productivity, changes in land use, access and effects of shading pasture to achieve a compromise so that the concept would work for the farmer and fit into the environment.

Environment Bay of Plenty was invited to help with the plan, especially as it involved retiring waterways and reducing erosion. However they could only take on the very worst gullies and insisted on an eight-wire fence. As there was no plan to graze sheep the Hicksons felt they could do the job with two-wire fencing, take in a far bigger area and avoid the compliance, covenants and delayed timeframe that would be imposed.

It could have been an ideal project for an Afforestation Grant. However the application process was outside of the timeframe and there was uncertainty about getting the grant, so the decision was made not to go down that line.

Assessment before planting

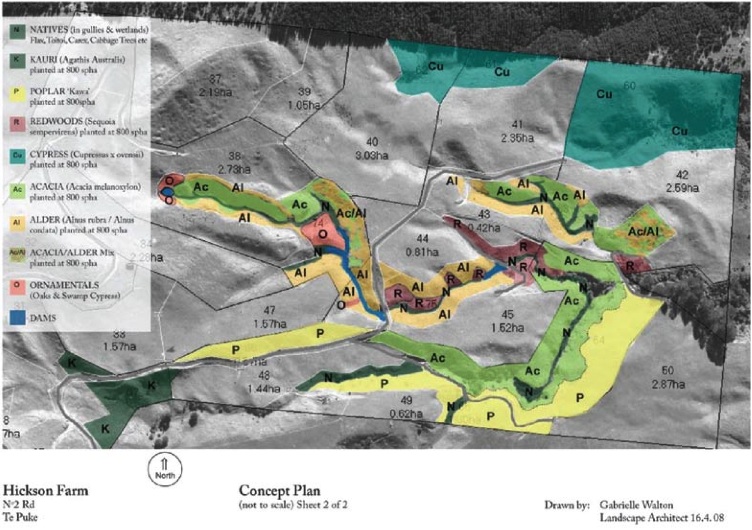

The areas to be planted were assessed for soils, erosion, springs, wetlands and water runoff, shading effects, fencing, access, remnant natives, as well as views into and out of the farm. Forestry plantation style plantings were considered the most cost effective way of planting the valleys, but growing trees for timber was not the sole objective. Species, spacing and management decisions were made to include erosion control, weed control, shelter and shading of adjoining paddocks, timber management, biodiversity and aesthetics. A concept plan was developed and discussed, alterations made to fit farm management and budgets and then the plants ordered.

Gorse and blackberry patches were sprayed and then planting took place in late May to catch the last of the warm soils and weather.

Acacia and alder were chosen as backbone trees to the scheme. Blackwood, Acacia melanoxylon, because it could be a timber tree if required or just left to blend in with the native remnants. It is not a particularly tall tree, nor too dense from a shading perspective. The alders Alnus rubra, A. cordata and A. formosana, were also chosen for potential timber value, size and shape of tree, ability to fix nitrogen and grow in difficult sites. In addition, being deciduous they would reduce winter shading to the south and would look attractive mixed with the acacia and redwoods.

Red alder, A. rubra, is not a common timber species planted in New Zealand. A North American native, it was historically considered to be of low value for timber, but is now becoming one of the western USA’s more important hardwoods. Red alder is easily worked, glues well, takes a good finish and is increasingly being used for furniture and cabinetry.

Cypress were planted in a difficult boundary corner shaded by the neighbour’s pines. Because this area is separate and easy to harvest the cypress will be managed for timber production. Poplar wands were planted as a deciduous tree on the drier, more exposed sites adjacent to paddock where shading would be an issue.

A meandering trail of redwoods and swamp cypress were planted between two dams at the base of a valley to allow for their height, and ornamental oaks used in key visual areas.

A hectare of kauri and kahikatea were planted as a forest trial for Scion. The location merged in well with the neighbour’s remnant bush and along a riparian finger which will slowly revert to natives. Flax and toe toe were used around dam and wetland edges.

Looking good

Six months on and the project is looking good. The farmer is no longer worried about awkward corners and difficult gullies and can concentrate on producing the best grasses off his easiest pasture. The two-wire electric fencing works well and gave us huge flexibility in following changes in contour. The streams run clean and clear and we are beginning to see seedling natives emerge in the fenced off gullies. The tree species have had one release, and other than initial hare problems with the acacia, there has been a good success rate.

Decisions will need to be made on silvicultural regimes if the Hicksons decide to grow the trees planted for timber. But with harvesting 40 years off on the species chosen, there will be plenty of time to enjoy the benefits of running a flat farm around forested valleys, with clean streams and an enhanced appearance.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand