Cattle want shade trees in summer

Keith Betteridge, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2014.

A severe drought, the best winter in years, then wet spring soils, fallen trees and shelterbelt damage – what more will be thrown at us? Farming was never promised as an easy road to wealth creation. However, making the right choices to cope with adversity and capitalising on good opportunities as they arise are possibly what defines a good farmer.

My first research appointment was to the Kaikohe Regional Station of DSIR Grasslands. When I arrived in the far north, I could not understand why the land had not been cleared of trees and scrub as had most of the rest of New Zealand. When returning to the Manawatu 12 years later, I could not understand why so many farmers had cut down nearly every tree on their farm. This mental flip-flop did not lead to the research looking into the value of shade trees in the summer-dry East Coast hill country, but it supports my view that having more trees on the farm, rather than fewer, is good. Let me explain why.

Animals seek shade

Like it or not, we have many long hot summers and that might increase due to climate change. During summer, livestock are likely to be out in the sun for up to 12 hours, and several hours could have an ambient air temperature hovering around 30°C. If trees are available then animals will always look for shelter during at least some of the very hot mid-day sun. We have all seen it, yet many farmers seem not to link this behaviour to the animal’s desire to be comfortable.

Sheep and cattle will often be seen in shade from about 8:00 am to 9:00 am in summer when air temperature is probably lower than 20°C. My interpretation of this is that they will have been grazing since sunrise, have had their fill, so need to lie down to ruminate. This phase of digestion releases a large amount of heat which is very good in winter, but not needed in summer, so why exacerbate the problem of heat dissipation by lying in the sun?

A discussion group in Porangahau sponsored by the Sustainable Farming Fund debated the relative merits of providing shade for cattle on summer-dry hill country. Many were of the view that if cattle are under shade then they cannot be eating and therefore will not be grazing causing a loss of income. Others argued the animal ethics question, while recognising that cattle do not graze all day long, which is income neutral. However as there was little science data to support either argument, AgResearch was asked to undertake a short experiment to provide some hard facts.

Trial details

Porangahau farmer Brenden Reidy, who manages the Parson Estate Trust farm, provided the perfect testing ground with similar sized adjacent paddocks of which two had spaced planted willows and two had no trees. AgResearch had sensing equipment for 24 cows, six in each paddock. The stocking rate of 2.1 Angus cows with calves per hectare was made uniform with additional non-trial animals.

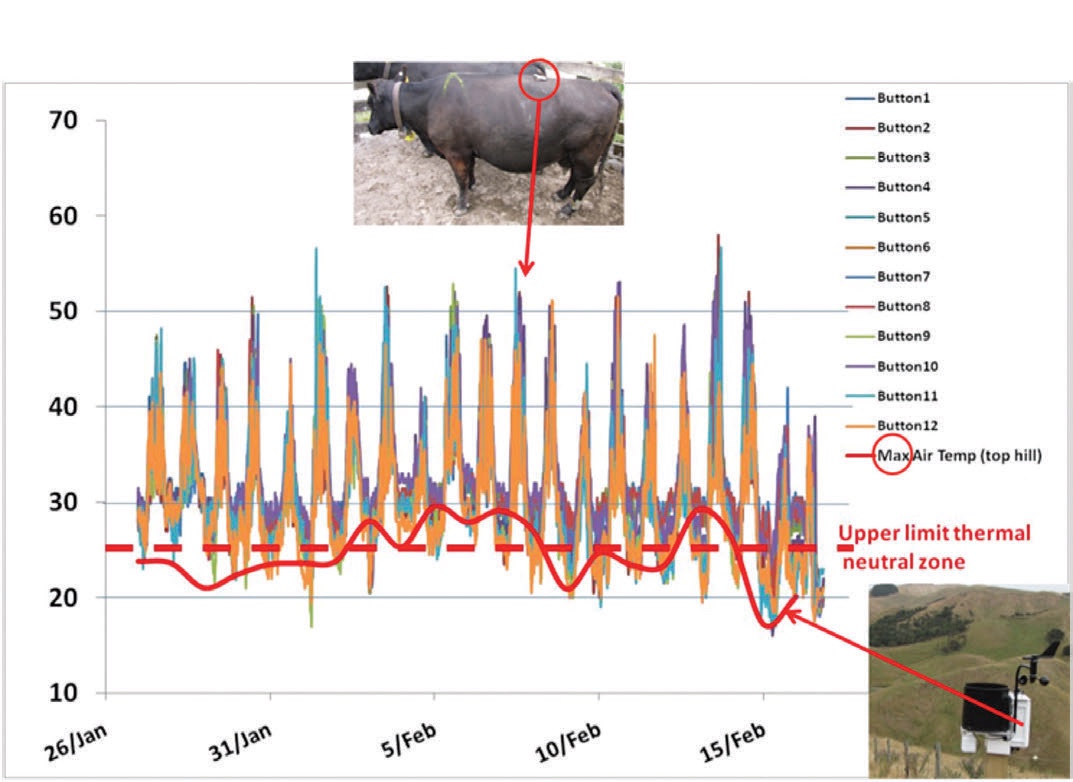

The GPS collar told us where the cows went within the paddock over the 21 day trial. Button temperature-logging sensors inside a piece of rubber cycle tube, to replicate the black hair of the cow, were glued to the back of the cows. These logged temperature every 15 minutes.

A motion sensor was attached to one hind leg of the cow so that we could match grazing, standing, walking and lying down to GPS positions in the paddock. Finally rumen sensors were put in the rumen of four cattle in each of shade and no-shade treatments. These logged rumen temperature and the acidity or pH.

We were also interested in where cows preferred to drink. Where a paddock had both a trough and a dam or an unfenced stream, at times these were isolated with an electric fence so that only one source of water was available. Cows had free access to all water sources for the first five days and the last five days, and in between these options were varied. Water temperature in the troughs and dams was also monitored. Pairs of button temperature loggers were placed around one paddock, one fixed at 1.5 metres above the ground on the south side of a tree trunk. The other was fastened to a short white peg in full sun about 10 metres from the north side of the tree where there was no shade.

Finally, a surveillance camera which could be remotely controlled from the house was installed at the trial site. This enabled grazing activities to be recorded for subsequent analysis, and allowed Mrs Reidy to keep an eye on Mr Reidy to ensure there was no undue slacking.

The main benefits of the camera were that he worked hard when close to the camera, that a wild deer was seen on the farm, and neighbours came to the house to have a look at the trial which was 1.5 kilometres away. There was little scientific merit as the camera had to scan three paddocks, taking in only small parts of a paddock at a time, and counting cows at various activities was very difficult. We also learned that counting black cows in dark shade was impossible.

The results

The highest air temperature recorded in our meteorological station was only 31.6°C, which was not a typical hot January or early February season for this district. Mean daily temperature ranged from 14°C to 24°C. Night temperature averaged around 14°C. Nevertheless the average maximum air temperature was 10°C higher in full sun than in the shade and average daily temperature was two degrees hotter in full sun than in shade.

The temperature on the cow’s back frequently exceeded 50°C in both groups in the hours between 2:00 pm and 3:00 pm. Air temperature above the thermal neutral zone results in animals having to expend energy to keep their body temperature within the normal range of around 38°C. In this trial cows were almost always above this threshold limit.

Shade cows were, on average, 2.6°C cooler than the no-shade cows at peak ambient temperature and 2.4°C cooler between 10:00 am and 4:00 pm. The high temperature on the backs of the cows was no doubt a result of the black hair of the Angus compared to lighter coloured animals, and represents the integration of both incoming solar heat and radiated body heat.

Not surprisingly, cattle with shade made good use of it during the middle of the day. The motion sensor showed that as the day headed towards peak mid-day temperature, grazing became closer to the trees. In this shade treatment the cows generally rested by standing and lying down in the shadow of the trees. At other times of the day resting, like grazing, occurred more widely across the paddock.

Of greatest revelation was that cows with shade still carried out some grazing during the period of peak temperature, but from between about 3:00 to 6:00 pm they grazed more than no-shade cows. Although there was a small reversal of this pattern between 7:00 and 9:00 pm, shade cows grazed 35 minutes longer each day than no-shade cows. Serious grazing starts at around sunrise and ends around sunset, but there is intermittent grazing during the night. We know from other work that this often occurs after a cow stands to urinate and that sometimes these cows will also drink.

Two interesting results came from the rumen sensor, the first being that we could count the number of drinks the cow had each day. More importantly, we noted that rumen temperature which should be stable at around 38°C to 39°C often rose to between 40°C to 42°C, at which temperature the cow had to have a drink no matter what the time of day or night. This must have been an indication of heat stress and was seen not in the afternoon, but typically in the period from 9:00 pm to midnight.

No-shade cows spent more time lying down during the heat of the day or suffered more heat loading, but drank with the same apparent frequency as shade cows. We could not estimate water consumption because much of it was from the stream or dam.

More efficient

Another positive feature of summer shade is, according to the literature, that the efficiency with which consumed feed is used is higher in cows without heat stress compared to those with heat stress. What is unknown from this trial is the liveweight change of the cows and calves. While we know that a three week trial is not long enough to confidently make this measurement, the trend was for the shade cows to have gained more weight than no-shade cows.

The water story is less clear cut. In one paddock when cows had free access to both a trough and a dam during the first five days, the cattle drank almost exclusively from the dam. However, after being forced to drink solely from the trough during one five-day period, when both trough and dam were again accessible together, the cattle drank almost exclusively from the trough. Mean diurnal temperature in the water troughs ranged between 14°C and 27°C, indicating that the cow’s ability to cool down is not great during the middle of the day.

The mean daily maximum surface water temperature on the two dams was 5°C higher than in the water troughs. So cows without shade get greater heat loadings and graze for a shorter time each day than cows with access to shade. Farm water systems are also likely to be so warm that ready relief from heat stress is minimal when they need it most.

Creating a magnet

Over recent years tree plantings in hill country have been made by many farmers for soil stabilisation. Some are no doubt made for improved animal welfare and many are plantation blocks planted for income diversity and aesthetics. One further attribute I suggest is that we are creating a magnet to have animals camping away from the riparian margins of streams where faecal nutrients and bacterial contaminants can be readily transferred to the water.

The area around trees will become a new critical source area in hill country. However, if these are distributed across the face of the hills, rather than concentrated along stream edges, this aggregation of nutrients back on the hill faces must be beneficial. More intense use of hill slopes because of increased fertility will also reduce the amount of rank pasture and increase the content of higher quality pasture species such as cocksfoot, ryegrasses and legumes.

Tactical use of electric fences can, where possible, also be used to force animals on to hill slopes to redistribute nutrients and change pasture composition towards high fertility species which provide improved nutrition for sheep and cattle.

It is well known that nutrients are transferred off the hill slopes to the flatter hill tops or gully floors in hill country because this is where animals camp. Enticing cattle and sheep on to the hill faces during summer should be good for stimulating hill pasture growth. The same may not apply for fenceline shelter belts because shade is only found on one side. Shadow from hedges will likely be less beneficial than from space planted trees where animals can follow the shade around the tree as the sun moves across the sky.

Perhaps we need to take closer note of what the animals are telling us – We need shade on hot summer days, even from early morning, so please replace what you have removed and we will promise to distribute excreted nutrients across the farm, stop sulking, and might even consider growing faster in return.

Plans are afoot to repeat this summer shade trial. This time we will concentrate more on animal performance to confirm that the additional 35 minutes each day of grazing time by cattle in paddocks with space planted shade trees translates to faster liveweight gain of young cattle.

Keith Betteridge is a Senior Scientist at AgResearch Grasslands based in Palmerston North.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand