Is your forest ETS compliant?

Ollie Belton, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2014.

With the crash of the New Zealand carbon market over the past two years, coupled with resurgent log prices, the Emissions Trading Scheme has faded into the background for most forest owners. For many the ETS is a failed policy and timber is back as the focus.

Despite the depressing state of the market, forest owners should not forget that the ETS and all its rules and regulations remain. Compliance is very real and should not be overlooked. The officials of the Ministry for Primary Industries take compliance seriously and have indicated they intend to ramp up spot checks and detailed site audits as time progresses. The penalties for non-compliance under the Climate Change Response Act are also very real, including civil and criminal offences.

Offences and penalties under the ETS

Civil penalties relate to calculating and surrendering emission units. If a participant fails to submit an emissions return by the due date, claims an incorrect number of units in an emissions return, or fails to surrender units by the due date, they are liable for an excess emissions penalty of $30 a unit. This is in addition to re-paying any outstanding units. If a participant knowingly fails to comply they could be liable to repay twice as many outstanding units in addition to $30 penalty per unit.

Criminal penalties include failing to collect information as required or submitting an emissions return without reasonable excuse. Fines range from $8,000 for a first offence, $16,000 for a second, and $24,000 for third and successive offences.

The more serious crimes under the Act have an element of intent such as knowingly or wilfully providing false information. These may lead to fines per offence of up to $25,000 for an individual and $50,000 for a company. Directors and managers of companies cannot shield behind limited corporate liability if it can be shown they had knowledge of the offence being committed.

The position on non-compliance is justified. Carbon forestry by its nature requires extra rigour and integrity as it is in essence the measurement and trading of an intangible commodity. Forestry has also been a pariah in international carbon markets because of the perceived risks of non-permanence and the potential for gaming. For this reason the largest carbon market, the European Union ETS, still excludes forestry offsets. Without robust legislation, compliance, and penalties, forestry under the ETS would be vulnerable to fraud and subject to international criticism.

Non-compliance

Since the ETS was implemented some people have raised concerns about the possible levels of non-compliance within the scheme and the implications for innocent forest owners. Because of the way forestry under the ETS has been implemented and the lack of checks and controls, inadvertent non-compliance may be widespread.

Most of non-compliant ETS forest participants are likely to be innocent offenders and also completely unaware of their offences. Despite this innocence, non-compliance could come back to haunt forest owners at a later stage, and at a cost.

The legislation and regulations governing the operation of the forest sector under the ETS are incredibly complex and have been constantly evolving and updated since first implemented in 2008. In the early years many professional consultants and advisors struggled at times to implement the rules correctly. Despite this, MPI have encouraged participants to carry out their own applications, emissions returns and other related duties. This is largely helped by the streamlined and user-friendly web based system which can lead participants down the first path of possible non-compliance.

Applications and mapping

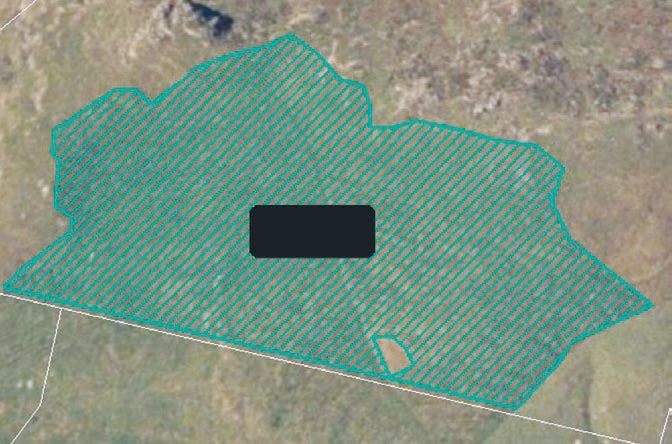

The first problem is whether applicants have an adequate understanding of the GIS mapping standard. The standard is very prescriptive about how to map your forest. For example, all gaps and holes which have widths over 15 metres need to be excluded from forest stands. However, accurate mapping not only rests on a solid grasp of the standard, but also on a reasonable knowledge and expertise of GIS analysis, especially for more complex forests which include multiple species and age classes.

Just as important is the quality of the underlying imagery to ensure a reasonable degree of accuracy. The online mapping tool provided by MPI is often the only reference map used by applicants for working out their forest areas. Between 2009 and 2012, the online imagery provided by MPI was often out of date, and at times did not show established trees with sufficient clarity to provide adequate guidance to comply with the ETS mapping standard. This meant that unless applicants sourced their own aerial photographs or satellite imagery, mapping forests could be a blind exercise. This can mean forest edges are not followed correctly, areas

of failed plantings are not excluded and areas of different trees species are not differentiated.

Areas incorrectly mapped

Poor mapping can lead to ineligible areas being included as post-1989 forest. However it can equally lead to areas of eligible forest being excluded. This has financial implications for landowners. If areas are then brought into the ETS, carbon can only be claimed to the start of the current five-year emissions period. Carbon sequestered by the forest in previous emissions periods is lost forever.

A commonly held misunderstanding is that during the ETS application process MPI carries out an eligibility assessment of the forest stands. This is incorrect. The GIS assessments are focused on determining whether the land in question is post-1989 forest land, in other words the land was not forested on 31 December 1989 or was deforested before 31 December 2007. Therefore forest owners should be aware that an approved ETS application does not mean an acceptance and determination by MPI of the forest itself as claimed.

Emission returns

The second major area where participants can be caught out is filing emissions returns and incorrectly claiming the units. The first of these stems from incorrect mapping. Many participants calculate their carbon by using the forest details taken from their ETS approved areas. However, participants should take the time before submitting a return to verify whether the registered areas have been correctly mapped, or whether there have been any changes in the forest structure such as storm damage which could affect carbon claims. Sometimes a quick search of free aerial images is all that is required. The next risk relates to the use of the carbon tables for calculating carbon. The methods and rules are very specific about calculating carbon and it is easy to get the process wrong. Simple errors, such as using the wrong age or region for radiata may result in small errors on an annual basis, but these can compound over time. More serious errors can occur where the wrong species group is used or age is mistakenly out by many years.

Again a commonly held belief is that MPI carry out detailed checks on emissions returns, and that an approval of a return and issuance of units is a final determination that a carbon claim by a forest owner is accurate. In reality annual voluntary emissions returns are not checked. In some ETS registrations it would be impossible for MPI to do cross checks as applications do not legally require species, age, or year of establishment to be given by applicants and voluntary emissions returns do not require this information.

The mandatory emissions return every five years does require a participant to provide information on species, age, and area. However MPI only carry out a cursory check which involves averaging the year of establishment and species group across a forest. MPI will only raise a problem if the numbers are significantly different.

Other problems

The field measurement approach is another area where mistakes can creep in. The rules and guidelines are very complex, particularly in dealing with indigenous forest and intermingled exotic species. The other problem can be a lack of continuity between the crew collecting the data and whoever submits it to MPI. Errors in data collection usually are not picked up until the data is submitted weeks after the job has been completed.

The question is how many errors in collection are understood and rectified?

Failing to submit emissions return is another non-compliance concern which is surprisingly common. This offence does not require any element of intent but carries criminal penalties.

Participant responsibility

The ETS regime is structured with minimal checks from MPI, and the burden of responsibility rests with participants to ensure they are complying with all the rules and regulations. This is confirmed throughout the process with signed declarations which refer to forest owner’s legal responsibilities.

In this way the ETS is similar to Inland Revenue’s taxation whereby it is the taxpayer’s responsibility to ensure compliance. Enforcement is carried out by the Inland Revenue with targeted and random audits.

Compliance

The good news is that MPI is focused on encouraging good compliance rather than punishing genuine mistakes. They use an unusual acronym VADE to classify participants.

- Voluntary − voluntarily comply and are informed

- Assisted − try to comply and are uninformed

- Directed − have a propensity to offend

- Enforced − have criminal intent and undertake illegal activity.

ETS participants who are non-compliant because of actions which are not deliberate normally fall under the assisted category. This means that MPI helps them become compliant rather than being heavy handed.

The legislation encourages voluntary disclosure of errors and the reduction of penalties in some cases. For example, if a participant voluntarily discloses an error in an emissions return then the excess emissions penalty of $30 a unit can be reduced to zero. The level of possible penalty reduction is determined on a case basis, and will depend on a number of factors which include −

- Genuine voluntary disclosure

- Participants willingness to assist

- Previous compliance history

- Reliance on professional advisors

Another factor to be aware of is if innocent and inadvertent errors escalate into more serious offences. This can be because participants fail to come forward after discovering a non-compliance problem.

Audit yourself

Most forest owners probably believe they are compliant but they should not be so complacent. Even professionals can get it wrong with some of the most serious problems that have so far come to light occurring as a result of using consultants. While it is reassuring to know that MPI have discretion to reduce penalties for genuine errors and voluntary disclosure, there still is a cost for the innocent in buying replacement units to account for over-issue.

Now there is a unique opportunity to buy cheap foreign credits and use those to meet an ETS surrender obligation. However, access to cheap units will be closed in June 2015. After this date the New Zealand units

will be the only eligible unit, and the price of these in the future is unknown. Some predict the prices could rebound to more than $10 a unit after 2015.

One strategy to deal with these problems is to voluntarily exit the scheme, and repay the government using cheap replacement units, which at the time of writing cost 14 cents each. Then when the forest is entered back into the ETS all mapping problems can be ironed out. This has the added bonus of wiping all the contingent carbon liabilities associated with the forest which would otherwise have to be repaid at harvest.

Steps for early 2014

ETS forest owners need to ensure they are compliant and should check their forest information carefully or engage a specialist to do this. If any possible non-compliance problems are found, then you should contact your consultant or MPI directly to discuss what next steps are required. Early detection and voluntary disclosure vital to lower risk and mitigate costs.

The integrity of the ETS also relies on good compliance. Therefore it is in the mutual interest of forest owners and the government to tidy up these problems while the scheme is still in its infancy.

Ollie Belton is the managing director of Carbon Forest Services Ltd, with over eight years of experience in providing the full spectrum of services to the NZ carbon forest owners.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand