A family project growing radiata pine

Tony and Chree Barker, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2015.

In the May 2014 issue of Tree Grower an article covered the harvest of Tony and Chree Barker’s trees in 2013. This article explains how and when the land was bought and the trees planted almost 30 years ago and then cared for until harvest.

The complete cycle of clearing gorse from the land and then growing and harvesting a small woodlot has provided more notable benefits than a simple financial return. Strictly following Neil Barr’s model of wide spacing and annual pruning of the butt log, produced less than ideal tree form. However, the low stocking rate meant that all silviculture work could be carried out on time without needing to use outside labour, minimising the overall cost. Although the trees were downgraded because of taper and heavy branching, the return was better than we expected when the family project was started.

In 1984 my wife Chree and I purchased a 16 hectare bare block of land at Kaukapakapa with the aim of planting trees as an interesting family project. At that time timber prices were low and financial profit was not the motive. We half expected the overall costs of this hobby to exceed the eventual return and so we set out to do all the work on the property ourselves to minimise these costs.

The land itself was relatively cheap, being the residue of a large farm subdivision, with a moderately steep contour, two gullies and a stream crossing. Approximately a quarter of the property was covered in regenerating bush in the gullies. The first major problems we faced were that the bush and the much of the open area were infested with gorse.

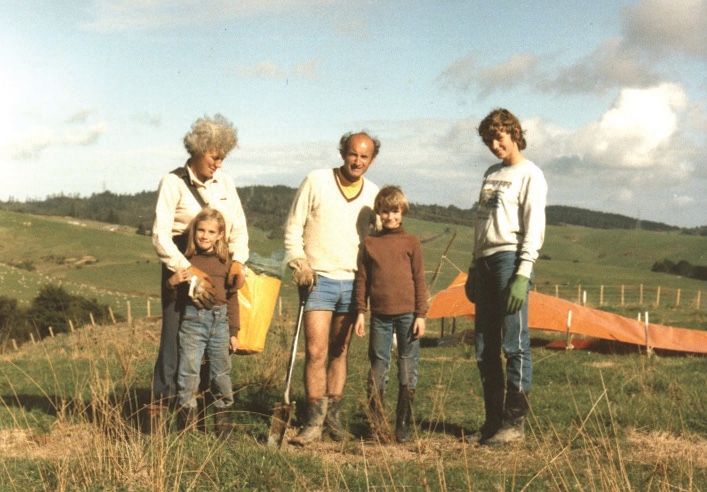

This was to be a family project which included our three children, Louise then 12 and twins John and Wendy aged seven. Without their contribution over the years, we would not have achieved our goal. It was never our intention to live on the property which was a 35 minute drive from our home. This was just another spare time hobby to fit in with our sailing and a busy family life. Had we known what we were letting ourselves in for we might never have begun. Such is the starting point for many of the worthwhile projects we all undertake.

Our children quickly learned the work ethic. They either worked on the property or played, there was nothing in between. They rarely opted to play and enjoyed the physical challenge and sense of achievement with each day’s progress. They also soon learned the connection between the value of a dollar and the work entailed in earning it.

Controlling gorse

Clearing the land proved to be the most time consuming task. It far exceeded the time required to plant, release, thin and prune the trees, but we were determined to rid the property of gorse. I chain-sawed it, the family hauled it, usually uphill to stacks where it was to be burned. We taught the children to concentrate on the area we were working on and not look ahead at what we still had to do. At times, the scale of this part-time hobby seemed to be beyond our capacity, but we persisted.

For many years we sprayed up to 300 litres of herbicide mix each year on the constantly re-emerging seedling gorse, but after about eight to ten years the re-growth rate rapidly declined. We never allowed a new gorse bush to emerge for long enough to form seeds. Although some seeds can survive for many years in the soil, the drop-off rate of viable seeds appears to be exponential. For the past 10 years, I have used less than 10 litres of herbicide mix once a year and need to spend several hours searching for tiny gorse seedlings to use it on. I dreaded the effect that logging and consequent soil disturbance would have on encouraging re-growth, but there has been minimal soil disturbance in the areas that had the worst gorse cover and so hopefully this may not be a major problem after all.

Planting regime

We knew nothing about planting trees and were extremely fortunate to have Neil Barr living close by to advise and encourage us with his extensive knowledge and kind nature. We followed his regime of wide spacing and although this is no longer in favour, it did reduce the total number of trees we had to deal with, enabling us to prune all trees every year for the first 10 years of growth to a final height of 6.5 metres.

The first two blocks were planted with pine in 1985 and 1986, using orchard seedlings, at eight metre by eight metre spacing. I also experimented by using cuttings for every fourth tree in the second block. The cuttings grew faster for the first few years and these were the most commonly retained trees when it came to later thinning.

Cyclone Bola arrived in March 1988 and caused extensive damage to trees and property. About half the three-year-old trees in the first block were flattened and had to be thinned out or propped up again repetitively after the numerous storms we had that winter. We did not have the heart to start again. The residual root damage meant that these trees were subject to a depressing windfall rate for the next 10 years.

The second planting was in a more sheltered area but did not fare much better. The logs from both these plantings were downgraded because of trunk distortion and tapering, together with heavy branching above the pruned log due to a combination of genetics and wide spacing.

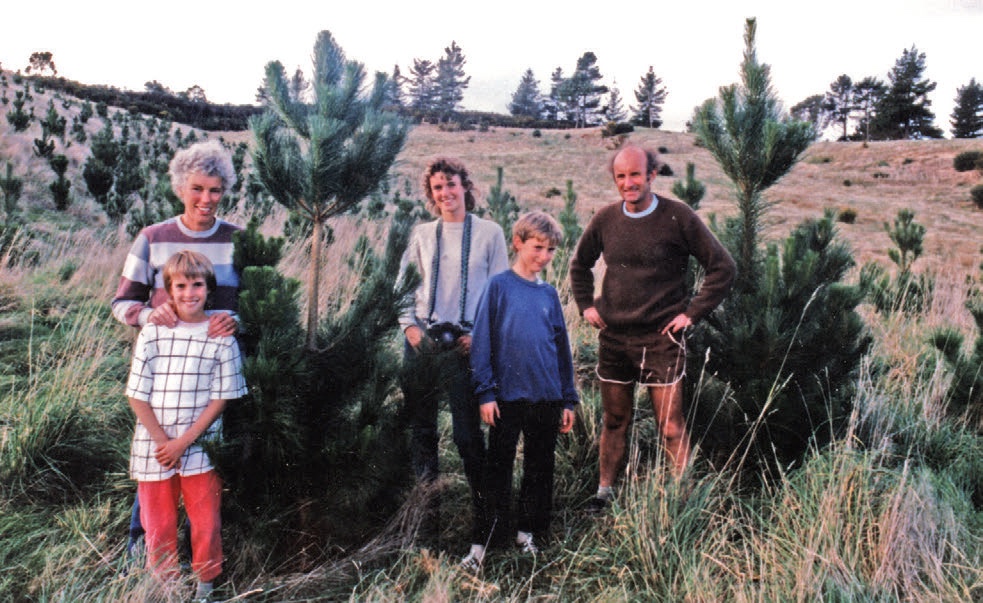

The third block was planted with radiata pine in 1993 using GF21 stock. Neil suggested that we plant the trees in groups of three in rows at eight metre centres.

This reduced the number of trees required by a quarter and made selection for thinning very easy. The runt of the three was thinned first, leaving a selection of one out of two for the final thinning.

If there were no obvious difference, then it did not matter which tree was thinned. It was much faster and easier to compare the trees when grouped together and of course the final spacing was perfectly even, meaning minimal competition for light or water throughout the growing phase. Despite the wide spacing, these genetically superior trees produced relatively light branching and eventually caught up with the earlier plantings. Even though they were only 20 years old when felled, they were our most valuable logs on a discounted cash flow basis.

Dry weather

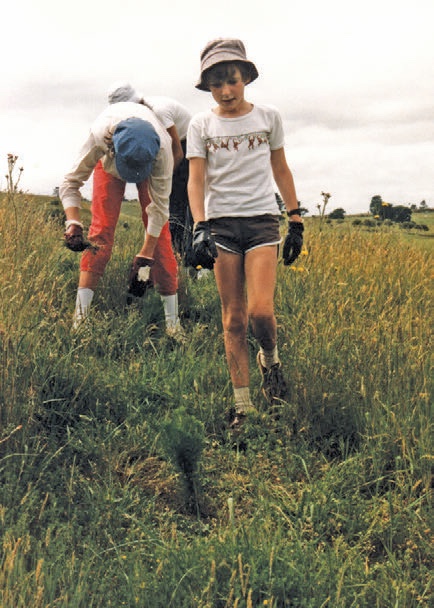

The year of 1993 was particularly dry with less rainfall that year than the Auckland drought year which followed. We planned to plant in May, but delayed while we waited for some rain. A few brief falls in August encouraged us to plant, but then there was no more significant rain. The seedlings were beginning to dry up, but rather than abandon them, we dragged containers of water up from the stream, cut a slot alongside each seedling, and hand-watered each of them with a litre of water.

It was another three weeks before it rained again, but only 12 of over 2,000 seedlings did not survive that extraordinary dry spell. Just what effect our manual watering had is unknown, but it made us feel better by trying to help.

Pruning

All the family helped carry out pruning while the trees were small enough for us to do so from ground level. Most of the ladder pruning was carried out by myself, until my son John grew up enough to do far more than his share of the higher pruning. We picked up and stacked all the pruned branches until they dried out and then they were burned. As a result, the plantation looked more like a park than a forest. Although this was like gardening on a grand scale, it did make the forest relatively fire-proof. One major fire swept on to our property from neighbouring council land on a hot summer day with the wind gusting to 50 knots. It could have destroyed much of one block of trees if the understory had not been cleared. Instead, it simply burnt the grass between the first four rows.

We have a symbiotic relationship with our neighbours. They get free sheep grazing between the trees and we get short green grass which eliminates the fire risk and aids weed control. The clear understory also made pruning safer.You always knew the ladder was on firm ground. It made it easier for the logging team to do their job and leave the property in good order.

We also planted about 250 blackwood Acacia melanoxylon. Those which we planted in the open areas were subject to psyllid damage to the growing tips, which made it very difficult to maintain good tree form. Those planted in light wells in the bush were never infected with psyllids and have grown to well formed trees of a good size. There seems to be very little demand for this timber and so they will remain as amenity trees.

The benefits

Despite the major downgrading of logs from the first two plantings due to log taper and the poor quality of the upper logs, the financial return from harvesting the pines has been better than we expected. The export log market was buoyant when we began harvesting and this continued until after harvesting was finished.

However, the main benefits were not financial. It gave us a great deal of personal satisfaction and sense of achievement as a family to create a woodlot from gorse infested land. Our children learned that perseverance and hard work does bring rewards and all three have applied that lesson to their own professional and sporting achievements.

John developed an interest in forestry and went on to train as a forestry scientist at Canterbury University. After a period with Forest Research in Rotorua, CHH Forests, and a year with the Forestry Commission in the UK, he now works as an investment forester for GMO Renewable Resources in Rotorua. He was my agent for the harvesting phase. This allowed me to stand back and be entertained by the process rather than having to make decisions and struggle to understand some of the complexities involved.

Harvesting

Other than fencing and some help to cut down a few large wind fallen trees, this was the first time we had employed anyone to work on our property. Woodbank run by Darrin Collett was a reliable company to work with and their friendly logging gang appreciated and took good care of our property, leaving it in a very tidy state. The stumps were cut close to the ground to maximise log recovery and the branches were raked into modest-sized heaps. The crew had to cope with exceptionally wet weather and the minimal soil disturbance is a credit to their forethought and skills with a digger. It was ready for sheep grazing just three months after tree harvesting.

The heaps of branches were burned in the following autumn, weed control will continue, and the stumps will be left to rot before we decide what to do next with the property.We are not re-planting. It was always planned to be just a one-cycle family project.

We spent a total of 2,500 man and child hours on the trees including everything from spraying the spots, planting, releasing, and annual pruning for the first 10 years, picking up and burning the slash, clearing wind thrown trees. About half of this was my time,the rest being contributed by Chree and our children from aged seven upwards.

Despite the major downgrading of logs from the first two plantings, due to log taper and the poor quality of the upper logs, the financial return from harvesting has been better than we expected. Approximately 10 hectares were planted and this yielded 4,350 tonnes of logs, with a before tax net return of over $150,000 for 2,500 hours of work by ourselves and our children.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand