The air is different: Another view of New Zealand’s response to climate change

Howard Moore, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2016.

Back in 1990 Bill McKibben published a book called The End of Nature. An editorial writer for the New Yorker, McKibben wrote the book in an early attempt to bring climate change to a wider public. In today’s terms it was not particularly scary, but early in the book he made two points that stuck with me. The first was that the air we breathe is no longer clean anywhere on the planet. We have changed it. We have, for the first time, overwhelmed the capacity of nature to clean up after us.

The second point was that where McKibben lived in the Adirondack mountains, the local forests were migrating north. They had been doing so for the past 12,000 years as the glaciers retreated leaving open land to colonise. The rate of spread of their northern edge was around a kilometre a year at most. McKibben noted that a 0.5° C of global warming represented a latitude shift of about 50 to 80 kilometres. He thought that with open land and the best conditions, by 2100 the forests might spread northwards by 80 kilometres, but with an expected temperature rise of 2°C over that time, it would not be enough. Stressed by the warmer climate the forests would die, and he realised that the landscape that he knew and loved was already changing. It hit me that all forests have a similar future.

I do not know McKibben’s political colours but I doubt he is a Republican. In New Zealand of course our political parties largely agree that climate change is a man-made problem, but we cannot agree what to do about it. On 25 September this year the Green party hosted a one-day conference at Parliament to discuss a sector-by-sector analysis of New Zealand’s capability to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It was hoped that if all of the political parties could meet and agree on the analysis, we might take a positive contribution to the Paris talks in December. The aim was rational, the conference was well attended, the analysis was comprehensive and we all learned a good deal – not least from the total absence of the National government.

Here is a personal review of that conference, highlighting some of the points I found most surprising. If you would like to read the originals in full, references to the sector-by-sector analysis and the conference presentations are given at the end of this paper.

Assumptions and constraints

The analysis was framed by two major beliefs, which unfortunately do not seem to align with stated government policy or policy advice. In 2014 Treasury tabled a paper which suggested that the country might achieve a greenhouse gas domestic abatement of around four per cent if carbon prices rose to $125 a tonne −

- Because the aim is to improve the atmosphere, New Zealand must actively reduce greenhouse gases and not rely on carbon trading to meet its domestic aims

- The cost of inaction will be higher than the cost of action at almost any carbon price and delays increase the cost curve.

Within that framework, and given that our present net emissions are 68 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent each year, the driving assumption was that we would aim to achieve zero nett emissions by 2050. A linear decline to that point from today would take us through 40 million tonnes by 2030, corresponding to 40 per cent below 1990 levels. The main constraints were that the steps to reduce greenhouse gases had to be practical, affordable, and did not rely on the deployment of new technology.

Should we fail to reach our fair share of greenhouse gas reductions by domestic action, we could meet our international obligations not by buying credits, but by assisting other countries to reduce their emissions with aid or technology transfer.

Forestry

The only real surprise here was how much the ideas of the speakers aligned with the climate change submission the NZFFA made in June 2015. They noted that

the mass of our forests and carbon sequestration will increase if the estate expands. They identified 1.3 million hectares of erosion prone land widely scattered across both the North and South Islands, which was cleared for farming and is suitable for forestry. Of this, they regarded 560,000 hectares as highly productive and with suitable protection should be kept for grazing purposes. The balance could be planted under a programme of planned, integrated land use.

Much of the plantable area was thought to be Maori land, and it was suggested that Maori communities might actively bring it into production if the price of carbon rose to $15 per New Zealand Unit. The Treasury report noted above did not mention Maori land, although it did assume carbon prices might rise to $50 by 2030.

Energy

National emissions in the energy sector of 35 million tonnes a year are dominated by transport and manufacturing. Road transport accounts for 90 per cent of transport emissions, with freight responsible for 30 per cent and passengers 60 per cent. The level of emissions results from a combination of fuel efficiency and kilometres travelled.

While fuel efficiencies are rising and kilometres travelled are falling, these changes are slow. We can cut greenhouse gas emissions at the desired rate if we introduce biofuels for heavy transport, opt for more electric passenger vehicles including public transport, and reduce vehicle kilometres travelled by adopting good urban design. Many urban residents are already pressing for such changes to combat traffic congestion and improve commuting times.

Agriculture

Mainly because we do not price in externalities, agriculture is the favoured land use in New Zealand. Our proportion of agricultural emissions at 46 per cent is much higher than other developed countries. Demand for farms has risen to the point where our farmers are some of the most indebted in the world. The drive for production is now threatening resources and animal welfare, and raising questions about our social licence to operate.

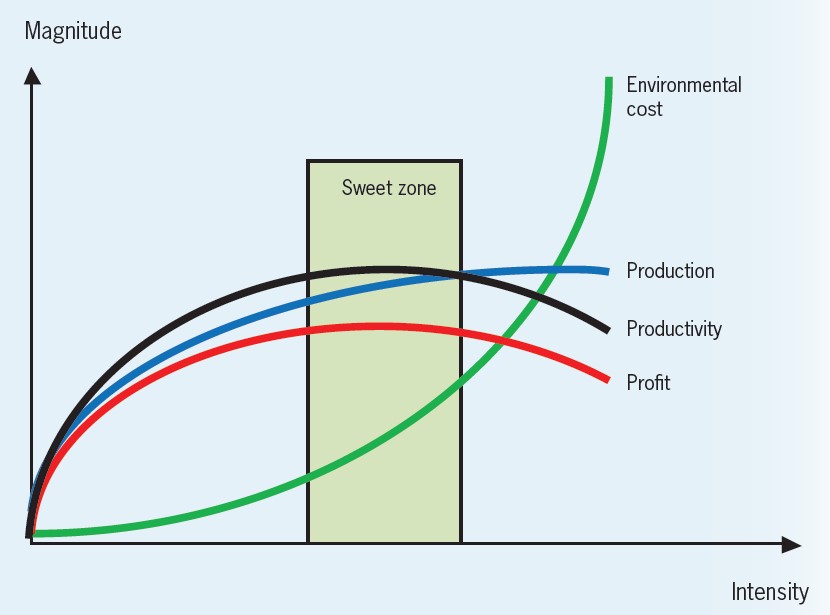

Every farm has biological limits and there is an optimal stocking where production, productivity and profit combine to form an operating sweet zone. We can improve profits and significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions by reducing farming intensity without necessarily sacrificing overall production.

Trials indicate that running between 20 and 30 per cent fewer cows on the average dairy farm can lead to reductions of emissions of oxides of nitrogen emissions and slight reductions in methane, while returning 20 per cent more production per cow. The increased farm productivity – with the same total milk but fewer inputs – can result in the same production volumes with an increase in profit of 50 to 100 per cent.

These results have been achieved in practice without introducing methane inhibitors or manipulating diets. They suggest that there is significant scope to reduce farm emissions by simply adopting best practice. To go beyond this level of greenhouse gas reduction we would need to switch from dairying to a non-ruminant land-use. This would have major implications and require substantial research, complete restocking and a total review of our agricultural training.

Conclusion

Despite reservations it was clear that we have the capacity to substantially reduce greenhouse gas emissions now, with present technology, simply by acting smarter and more cooperatively. I was encouraged by the shared belief that we can do it, and disappointed that the government seems to be both poorly advised and closed to the discussion. Of course the conference covered a lot more ground than I have reported, especially in relation to the Paris talks and what might come out of them. By the time you read this paper you will probably know all that.

PDF copies of the sector by sector analysis and most of the presentations are available on www.greens.org.nz/ page/conference-climate-protection

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand