This is free.

Radiata pine for the next generation

Michael Watt and Harriet Palmer, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2018.

Finally, payday is approaching for many forest owners, as woodlots and forests planted in the 1990s reach harvest age. For growers planning to replant with radiata pine, and any new planters, there will be many more opportunities to influence the results of future rotations.

This is in general partly thanks to research funding from the forest growers’ levy. Next Generation Silviculture research at Scion is developing methods of increasing the precision with which radiata pine can be sustainably managed throughout the rotation to improve productivity and profitability. Advances are the result of a growing understanding of how site, genetics and silviculture combine and interact to influence radiata pine growth.

For small and large-scale forest owners, research will enable a much more site-specific approach to predicting the effects of two fundamental decisions −

- Whether or not to prune

- Optimal final crop stocking with how many trees to be left standing following final thinning.

The current generation of radiata plantations

Piers McLaren’s Radiata Pine Growers Manual was the bible for many 1990s planters. The manual gives very clear and still relevant explanations of the whys and wherefores of pruning and thinning. It also emphasises that there is no one size fits all recipe for these interventions. Owners were encouraged to make their own decisions based on their objectives, site and the best information available at the time.

As a result, many of the current generation of forest owners have pruned their trees to a height of over six metres and thinned to final stocking densities of 200 to 350 stems a hectare. Some farm foresters chose agro- forestry regimes, with fewer than 200 final crop trees in each hectare, combined with stock grazing. Structural or unpruned regimes tend to be thinned to a final density of 450 to 550 stems a hectare. If everything has gone more- or-less to plan, many 1990s plantations will meet their owners’ expectations and generate good profits at harvest, especially if logs prices continue at current high levels.

What has changed?

In some respects, nothing has changed. Whether to prune or thin, and to what extent, will always depend on a range of factors – the owner’s circumstances and objectives for the crop, the site, tree genetics and target markets. The big advance now is that by combining different facets of radiata pine research, scientists are beginning to be able to provide far more site-specific information about the results of different pruning and thinning regimes. Models are revealing some surprising discoveries about the implications of these decisions on harvest volumes and values.

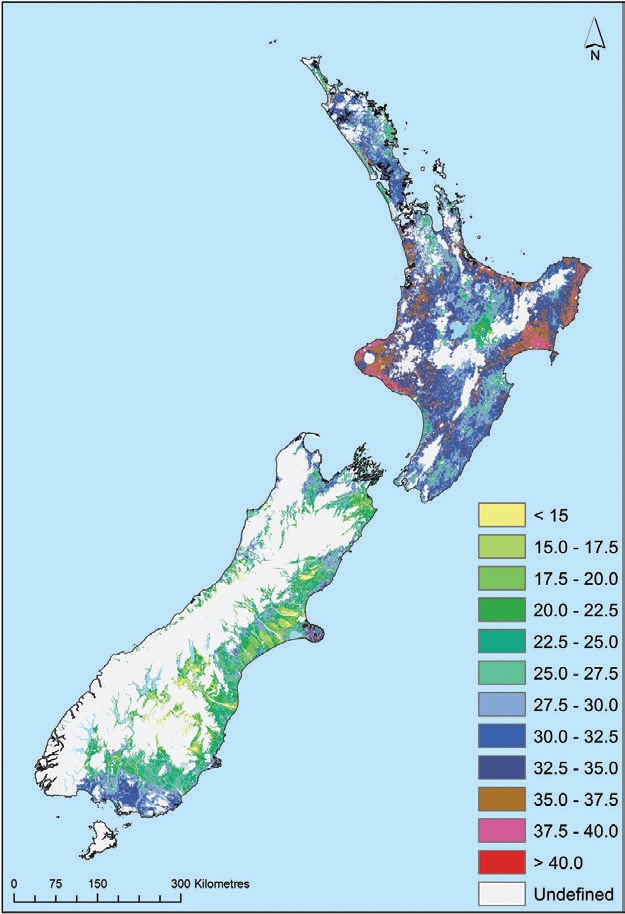

Site Index

Site Index is an index of site quality based on height growth. It is defined as the dominant height of a radiata pine stand at age 20 years. In New Zealand, it averages about 30 metres but can range from 20

to 40 metres. Site Index can be estimated for any stand from a measurement of height at a known age using a height and age model. Its advantage is that height growth is not greatly affected by stocking. Its disadvantage is that height growth is only moderately correlated with the quantity of wood grown in a stand.

300 Index

The 300 Index is an index of site quality based on stem volume growth. It is defined as the mean annual increment in stem volume at age 30 years for a pruned radiata pine stand grown at a stocking of 300 stems per hectare. This is the stem volume divided by the age − 30 years in this case − and averages about 25 cubic metres a hectare each year, but can range from below 15 to as high as 40 on a very fertile site. The 300 Index can be estimated for any stand from a measurement of height, mean diameter and stocking at a known age using the 300 Index Growth Model to adjust actual volume growth for the effects of age and stocking.

Describing the potential of a site

Optimum stand densities for a structural regime

Optimum final stand densities for a pruned P30 regime

Optimum final stand densities for a pruned P40 regime

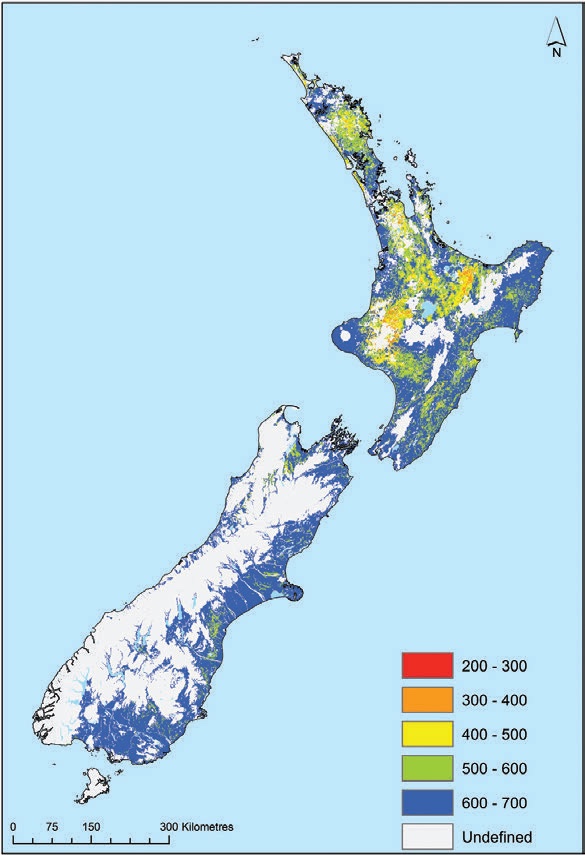

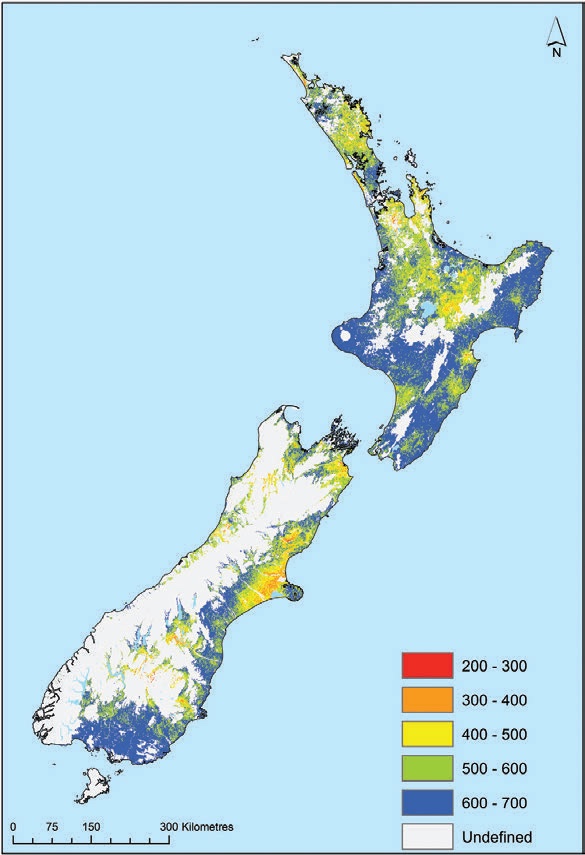

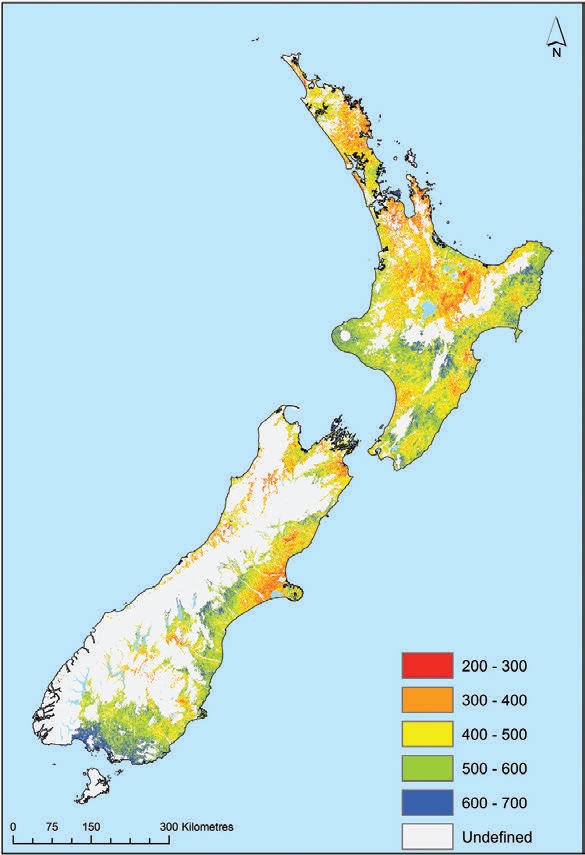

Two indices are used to describe a forest site’s potential to grow radiata pine in New Zealand − the 300 Index and the Site Index. As more environmental data becomes available, such as that gathered by remote sensing, sites across New Zealand can be determined at higher resolutions than ever before. Data is now available for the 300 Index and Site Index for all plantation forest sites at a 100-metre resolution.

Scion’s well-established Forecaster forest management software includes growth models for a range of radiata pine regimes, thanks to data gathered over many decades from the nationwide Permanent Sample Plot network. Site indices, combined with the growth models, enable scientists to ‘grow’ radiata pine under different pruning and thinning regimes and rotation lengths on different sites, and predict the volume of various grades of logs on a per hectare basis. Current log prices for different grades of logs, as well as average costs including those of pruning, have been added to develop scenarios of the financial results of different regimes on different sites.

Results from modelling

Using this model Scion have predicted radiata pine volume and value under three common regimes for 15 combinations of Site Index and 300 Index over a 28- year rotation across New Zealand –

- Structural regime producing S30 logs with a minimum small end diameter of 27 cm and maximum branch size of 7 cm

- Small log pruned regime P30 with a minimum small end diameter of 30 cm

- Large log pruned regime P40 with a minimum small end diameter of 40 cm.

For any given site and for each of the three regimes, the model calculates −

- Optimal stand density in stems per hectare

- Stand value as gross and nett values per hectare

- Relative value of pruning for the P30 and P40 regimes.

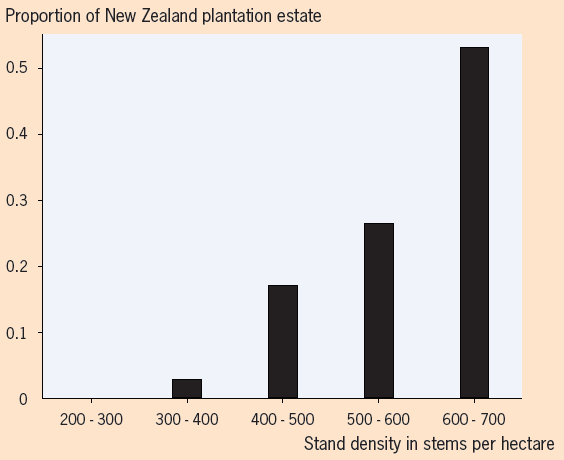

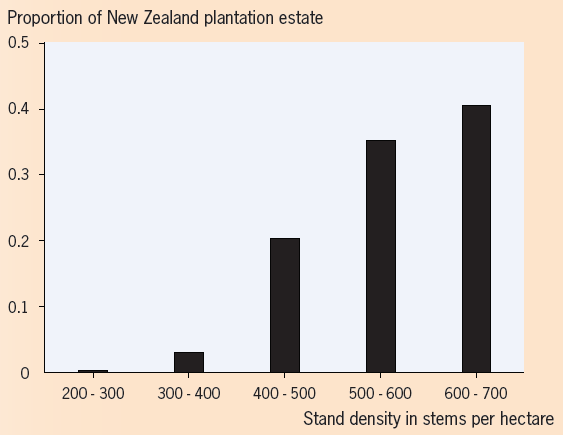

Optimal final stocking densities

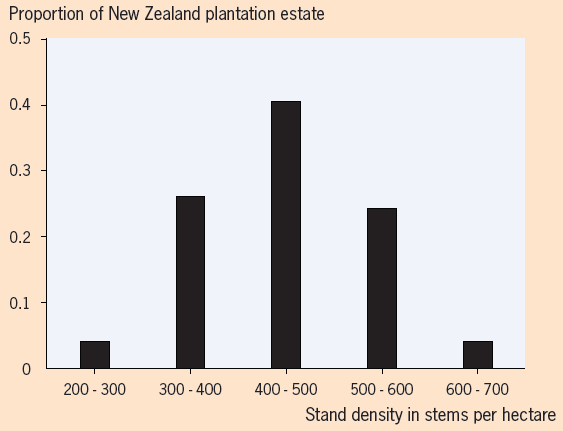

The model shows conclusively that, for all three regimes, higher stand densities than are currently the norm are likely to be more profitable.

Importantly, as can be seen from the maps, there is significant variation in optimal stand density depending on the site. This confirms scientists’ belief that there is potential for increasing productivity simply by more closely matching silviculture to site.

To prune or not to prune?

A second important finding is that there has been a strong decline in the relative profitability of pruning over the last 20 years. This applies to P30 and P40 regimes because the average pruned log premium over structural timber has declined steadily. Analyses show pruning to be profitable over the majority of plantations using values from 1995 to 2000, but unprofitable on most sites from 2011 to 2015.

The profitability of pruning appears to be very sensitive to site. The most profitable areas for pruning are located in regions where the 300 Index ranges from moderate to high and Site Index is relatively low. Under these conditions, the large volume for each tree − high 300 Index − is distributed over a relatively short stem length − low Site Index, which results in a high proportion of the stem with high diameter that meets the small end diameter restrictions for pruned grade logs. For growers, this again emphasises the importance of understanding site potential. As ever, personal preference and knowledge of markets may also play an important part in the decision of whether or not to prune.

Focus on structural grade regimes

Results from the analysis of the structural grade regime on a New Zealand-wide basis show −

- Optimal mean stocking of 614 stems per hectare

- Over 88 per cent of stands nationwide would have an optimal stocking over 500 stems per hectare

- An increase in nett value at harvest of $2,300 a hectare if the mean stocking of structural regimes was increased by 100 stems a hectare from the current mean

- Although optimal stocking is generally greater than 500 stems per hectare, it can be much lower on some sites, especially those with a low 300 Index and relatively high Site Index

The overall implications of these findings are significant. If all structural timber plantations are thinned at age eight to optimal stocking of 100 stems a hectare more than at present, over the next 27 years, the increased net value when felled will be $1.7 billion.This discounted income stream is equal to $156 million in 2017. Adding all the gross annual gains over the total period produces a total gain of $3.8 billion when the trees are felled. When this sequence of gross annual gains is discounted back to 2017 it is equivalent to $349 million.

Conclusion

The move towards precision radiata pine silviculture in New Zealand is well under way. Small-scale forest owners will benefit from the rapid developments in science-based knowledge and resources. This is thanks to levy funding. Managing trees on a site-by-site basis to meet prescribed productivity targets will become the norm, starting with selection of ‘designer’ seedlings to suit a given site and continuing throughout the rotation.

What does appear certain is that, for most sites and whatever the regime, the next generation of radiata pine is likely to have higher stocking than the current generation. Whether small forest owners choose to prune or not will remain a personal preference, but the decision can now be made in the light of better knowledge about relative profitability.

Finally, the problem for small forest owners of gaining access to information to help make these types of decisions should soon become much easier, with a new improved Radiata Pine Calculator; now aligned with Scion’s powerful Forecaster model, soon to be made available by Forest Growers Research.

The research in this article was developed by Michael Watt, Mark Kimberley, Jonathan Dash and Duncan Harrison, all of Scion. Harriet Palmer is an independent forestry communications specialist.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand