Light my fire

Hamish Levack, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2019.

During a field day at the Hokitika conference in 2016 we heard about the value of growing some trees for firewood, a concept which was at odds with those growing trees for timber. However, we were told that just 15 pieces of firewood from radiata pine grown on the West Coast brought in greater nett return to a forest owner than a full load of logs. The following article by Hamish Levack probes a little more deeply into the use of some trees for firewood.

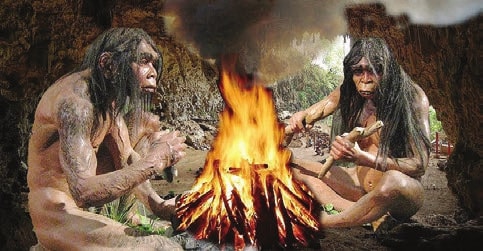

When Elvis Presley sang Light my fire in the 1960s he was using a powerful metaphor about a phenomenon which has been a key to the evolution of human civilisation. Fire provides warmth, protection, improvement in diet and technology. It permitted the geographic dispersal of our species, gave rise to cultural innovations and allowed human activity to proceed into the darker and colder hours of the night.

More than 100,000 years ago the use of firewood by humans was widespread, but during the last three hundred years or so coal, natural gas and oil began to replace firewood. However, the finite nature of fossil fuels and the new awareness that wood is a carbon neutral energy source means that firewood is reclaiming its importance as a fuel. The best type of firewood depends on what type of fireplace or wood burner you have, the time of year, whether you are trying to light a fire or already have a fire established or whether you want it to burn with as little input as possible.

The fuel energy of wood

Ideally the water content of wood fuel should be under 20 per cent, the lower the better, although it will burn with a much higher moisture content. However, more moisture means it is difficult to get the wood burning, leads to a drop in the combustion temperature which leads to increased smoke formation, higher emissions and a build-up of carbon in the chimney. Well-dried wood has twice the calorific value of freshly cut wood and when put on a fire should start to burn within 20 seconds.

| Condition of wood | Water content | Energy content |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh timber | 50 to 60 per cent | 2.0 kilowatts per kilogram |

| Stored for a summer | 25 to 35 per cent | 3.4 kilowatts per kilogram |

| Stored for several years | 15 to 25 per cent | 4.0 kilowatts per kilogram |

Assuming they have the same water content, all species of wood have almost the same energy content for a given weight. Hardwoods such as manuka, acacia and eucalypts are denser than softwoods like radiata pine because softwoods contain more air. Therefore, if we are considering equal volumes, rather than equal weights, hardwood has more energy than softwood. This is why a trailer load of hardwood is more valuable than a trailer load of softwood

The smaller the size that wood is split into, the larger to surface area to volume and the faster it will dry. It can take up to two years for wood which has not been split to dry well. A firewood stack will dry faster if the top is protected from the rain with a cover. It is also better to place your stack in a sunny and wind-exposed place. The thoughtful layering of a firewood stack will improve airflow and if the stack is kept at least 20 cm above the ground, moisture from below will not be absorbed.

| Firewood | Average cost per cubic metre | Heat output kilowatts per cubic metre | Price per kilowatt of heat produced | Burn time | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poplar | $100 | 1,200 | $0.08 | Fast burning | Soft hardwood |

| Eucalypt | $140 | 1,270 | $0.11 | Fast burning | Hardwood |

| Pine | $80 | 1,091 | $0.07 | Fast burning | Softwood |

| Macrocarpa | $130 | 1,150 | $0.11 | Slow burning | Medium density |

| Manuka | $180 | 1,860 | $0.10 | Slow burning | Very hard |

Splitting firewood

A good axe will split most wood, depending on the strength and energy of the person wielding the axe, but a hydraulic log splitter will be cost effective if you are going to do a lot of splitting. They cost from a few hundred dollars to several thousand dollars depending on the level of sophistication that you want. At the touch of a button and a lever you get tonnes of controlled splitting power. The more expensive models operate much faster have more power and usually also have adjustable log working lengths.

For those of you who split their own wood it may seem that a wood splitter is an un-necessary expense. But small electric powered splitter costing under $500 should last you many years, save a lot of hard work and will even split the knotty and difficult wood which is almost impossible with an axe. The risk of getting your hand or fingers caught in the machine is virtually non-existent as you need each hand to operate a separate control at the same time, meaning there is no spare hand or finger to get squashed.

Growing firewood

In deciding to plant your own firewood crop do not forget that by the time you are ready to fell the timber you will no longer be as young as you were. You will want to minimise the effort put into splitting. If you are only going to use an axe this rules out large stem diameters and large-branched timber and suggests that pruning may be advisable.

It is assumed that anyone contemplating growing their own firewood is not a dedicated economist but does so for philosophic or atavistic reasons. They will not be deterred by thoughts of interest rates when occasionally reaching for a pruning saw and taking a stroll to the plantation to trim off a few branches which will make splitting much easier later.

Faster growing timber is the natural choice and a eucalypt producing dense hardwood is a good choice. Even better is to make sure you grow one of the species which coppices. This means that when you cut the tree down, branches will rapidly sprout form the cut stump. As there is already a good root system in the ground, the new shoots will grow much more rapidly that the first tree. If you trim the shoots to leave just one, or a small number, of shoots, you will get some nice log-sized branches in just a few years and you can even cut them at a size which needs no splitting.

If you are growing firewood on a 15-year rotation and you plan to burn up to 10-tonnes a year, then all you would probably need is a woodlot of about a hectare in area. So that you can provide yourself with a sustainable yield you would need to plant a small plantation of about 25 metres square each year.

Wood burners

If the wood is hot enough the combustible creosotes and resins will evaporate out of the timber and will be burnt as gases. Where these gases are not burnt completely the result is more smoke. The evaporation of the gases turns the wood to charcoal, which then burns easily and cleanly and produces most of the heat.

To burn as cleanly as possible the fire needs to be as hot as possible. The fire also needs the right amount of air to support the combustion. Too much air will cool the fire and smoke is produced and not enough air has the same effect. Modern wood-burners burn efficiently because the firebox is lined with firebrick material allowing a hotter fire. The combustion air is carefully admitted to give the most complete combustion possible. The resulting efficiency of the conversion of the fuel energy into heat in the room is around 65 per cent.

The traditional open fire may be nice to sit round but admits too much air, cooling the fire and giving an efficiency of only 15 or 20 per cent. Some even have negative efficiency – they draw cool air into the house, warm it and send it up the chimney.

If you burn wood carelessly, or burn wet wood, you will generate smoke containing very fine soot particles which are a health hazard. Many towns and cities such as Christchurch and Nelson with nearby mountain ranges and prevailing winds that slow the dispersal of smoke, are at a particular risk of this. Before you buy a wood-burner, make sure your local authority will allow you to install the model you want. Many councils will only allow installation of models from their recommended list. If an illegally installed wood-burner causes a fire it will probably invalidate your insurance cover.

Freestanding models without a water jacket for heating water are generally the most efficient. They produce the most heat for a room for a given firewood load and they are also the cheapest to install. But if you have an existing open fireplace an insert model is often a good choice. Insert models are not as efficient as free-standing ones but they are much better than an open fire. If you have a non-draughty, well-insulated, home of average size in the north of the North Island then a 10-kilowatt stove should be sufficient. If the rooms are large with high ceilings you will need a more powerful stove. A less well-insulated house which is further south would probably need a wood burner which can produce up to 14 kilowatts.

Convection or radiation

All wood-burners heat the air and radiate heat, although some of them are marketed as predominantly one type or the other. It depends on the external design of the firebox. Convectors are best for well-insulated, non-draughty houses with low ceilings. Radiant models suit older, less-well insulated, draughty, houses with higher ceilings.

A convector type heats the air immediately around it. Hot air is lighter because it is less dense and so it rises away from the heater and gets replaced with cooler air, which is in turn heated. This convection air-current means that the warmest air in the room ends up near the ceiling with the coolest air near the floor. A useful addition is a small fan on top of the wood burner as shown in the photograph. This fan is driven by a thermocouple electric motor. As the fire warms up, the base of the fan gets hotter than the top and an electric current is created which spins the fan spreading warm air around the room much more effectively than natural convection.

A wetback stove uses copper pipes to circulate water from the wood-burner to the hot-water cylinder and back. They can be quite expensive to install and the hot water cylinder needs to be placed reasonably close to the burner and as mentioned earlier, because the water is being heated there is less heat for the rest of the house.

The payback period for a wetback, compared with the cost of using electricity or gas to heat your water, depends on how you use your wood-burner and the source of your wood. If you have grown the wood yourself, and do not cost your time of the use of your land, it is a very efficient system If you have to pay for the wood a wetback is unlikely to be cost effective.

The Benghazi portable wood burner

Those of us who used to work in Forest Service gangs have fond memories of tea made from water boiled in a thermette. This gadget, invented in 1929, by a New Zealander called John Hart, is simple, portable, efficient and still popular. It stands about a metre high with a conical chimney running through a water container. They were renamed Benghazis by the New Zealand Division during the war in North Africa who used them extensively. The places where our soldiers camped were always ringed with circles of scorched earth where the burner had stood. Apparently this puzzled Rommel’s troops.

From the Tree Grower 30 years ago

Firewood was the subject of a short article written by John Steven in Tree Grower in May 1988. Below is an edited summary of what was said all those years ago.

John Edmonds had presented a workshop trying to convince people that firewood could be grown profitably.

At the time of writing the article in 1988, firewood was quoted as selling for $45 a cubic metre in Dunedin. John’s study involved growing Eucalyptus nitens on an eight-year rotation and harvesting the area at least twice. The model showed that if easy land was available at $2,000 a hectare or less, and was within 20 km of the city, a healthy internal rate of return could be achieved, up to 8.3 per cent. Important factors to consider were −

- Distance from the market

- A fast growing species of dense wood which can be coppiced

- Easy topography for efficient harvesting

- Management skills to make sure the crop got off to a good start

The John Edmonds system involved planting 2,000 stems a hectare, then harvesting at eight years when the trees should average 15 cm and not require splitting. This would provide just under 200 cubic metres a hectare at each harvest. The coppice crop which follows made the venture financially attractive with a gross income of around $9,000 a hectare for each harvest. Over 24 years of three harvests, two from coppice, that was total a gross income of $27,000 a hectare.

There was discussion about direct selling and the reduction in income if using a wholesaler. But apparently the workshop made people think about firewood as a crop.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand