Breaking down barriers to afforestation

Michelle Harnett, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2020.

We all agree that planting more trees is good idea, but with the One Billion Trees programme, dealing with agricultural emissions and New Zealand aiming to become carbon neutral, how to go about it remains a hot topic. Most New Zealanders are concerned about protecting the land. Whether expressed though a farm’s mission statement or the concept of kaitiakitanga, we all care about the sustainability of the environment and enjoying its benefits, and have a stake in seeing the right tree is planted in the right place for the right purpose.

People’s perception and planting

Fears about the blanket planting of productive farmland are understandable and not restricted to New Zealand. Conflict over the perceived environmental, economic and social effects of planted forests has been reported in Australia, Ireland, Scotland and the United States, to single out a few examples.

Objections are commonly raised about the establishment of large-scale plantations by non-farmers, which are seen as providing more benefits for owners than positive outcomes for the wider community. Afforestation also goes against landholder values about appropriate use of agricultural land and loss of land management flexibility.

Similar objections and opinions have been raised locally.

News that two large New Zealand farms have been sold off-shore, largely for forestry is depressing according to 50 Shades of Green spokesman Mike Butterick. ‘It’s bad enough having the land sold to foreigners but having good productive farmland sold for forestry and subdivision is criminal,’ Mike Butterick said. ‘Once the land is sold for forestry it is effectively lost to food production. You cannot eat trees.’

Sales of farmland to overseas interests for conversion to forestry aside − 14,300 hectares between October 2018 and September 2019 according to the Overseas Investment Office − private land owners have, and continue to, plant trees and forests on their land. They are valued for their potential to provide a diversified income stream, increased resilience to storms with other environmental benefits on and off their land.

Success factors and barriers

Tree-planting land owners report common elements to success. One is having integrated land management where the focus is on optimising the use of different land blocks to increase overall productivity and profitability. Trees become a part of good farming practice and are planted with a clear role in mind. Examples include land management, diversification, cashflow, succession planning, workload reduction or long-term investment. Other benefits which enhance the overall operation often become apparent after initial planting, with shade, shelter and feed helping improve animal welfare, aesthetics, social licence for farming and forestry and better mental health among them.

Successful land owners also show a willingness to learn, adapt and improvise around main issues such as species suitability, planting, access and extraction practicalities and financial structures. They also report taking advantage of grants or incentive schemes to help with the up-front cost of initial planting and fencing.

Trees bringing income

Hawke’s Bay farm forester, Mark Warren, provides a good example of how forestry can be used to spread risk and contribute to a more resilient business. Waipari Station is a coastal farm running about 10,000 stock units with around 270 hectares planted in production and protection forestry – mostly pines, with some eucalypts, some cypress and blackwood. A large part of the property’s income now comes from forestry, with the average return often almost double the wool cheque, as well as carbon sequestration value which is close to the value of the wool cheque.

A severe and localised storm which hit the area in late April 2011 caused an estimated $250,000 in losses on the farm. Mark reported that the flood gates at the bottom of forestry blocks were intact but the unplanted country flood gates were all gone. ‘The tree income bailed us out ... Many neighbours have still not recovered.’

Assessing risks

Among the perceived barriers to tree planting, financial risks are a major consideration. In the short term this relates to setup costs and the pressure this can place on the economic sustainability of the overall operation. There is also the worry of perceived loss of productivity from converting land to trees. From a longer-term perspective, the financial risk relates to the uncertainty of the income the trees might generate in 20 to 30 years. This can be compounded by a lack of familiarity with the workings of forestry operations, particularly compared to other familiar farm activities.

The risks around implementation present another barrier. These come from a lack of knowledge or expertise around selecting the right sites and species or timing the planting. Comparing these uncertainties with other familiar activities with more certain results can mean that tree planting can end up in the too-hard-basket.

The reputational risk in moving away from what is considered traditional farming is also a barrier. This risk is heightened in the current context of the community discussion leading to tree planting being portrayed as anti-farming when carried out at scale.

Putting right tree in the right place into practice?

One of the ways to support land owners who would like to plant trees but are unsure how to go about it is to show them how planting the right tree in the right place works, and the benefits planting can bring. Scion and agricultural and forestry consultants have recently finished a project looking how afforestation can be used to control erosion in the Hawke’s Bay.

The work was at the request of the Hawke’s Bay Regional Council and the Hawke’s Bay Regional Investment Company and partly funded by the Ministry for Primary Industries. The aim of the work was to overcome some of the barriers presented by lack of knowledge and experience, and explore how land owners who would like to plant trees could be supported,

Where to plant

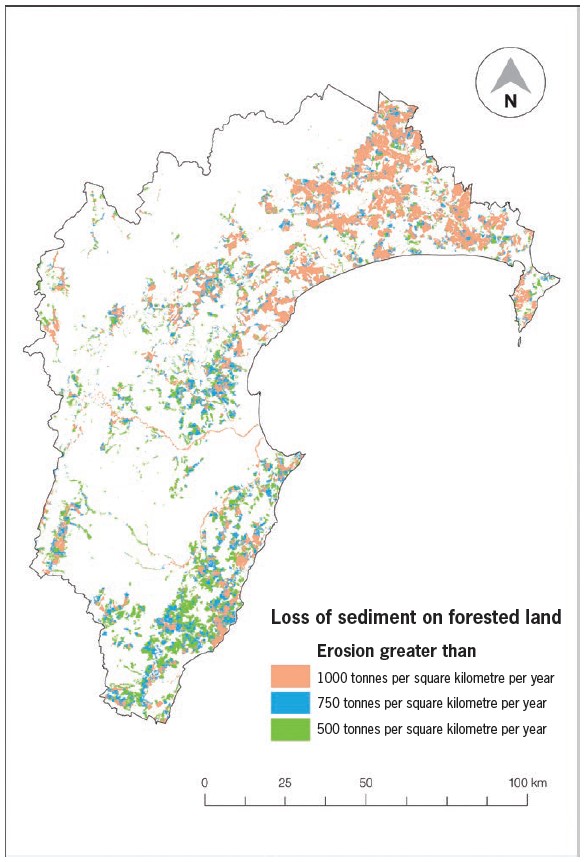

The first step in the project was identifying erosion-prone land that could be suitable for afforestation. Sediment yield mapping has identified 150,000 hectares or 12 per cent of Hawke’s Bay land losing at least 1,000 tonnes of material per square kilometre each year. The majority of this comes from sediment moving from pastures into waterways.

Scion scientists developed Afforestation Groupings from land use classes because these land use classes tend to be coarse in scale. By incorporating factors such as the degree of erosion, slope angle and whether slopes face the direction intensive storms normally arrive from, highly erodible sites can be identified on a 25 square metre scale. This helps with deciding if land is suitable for commercial forestry or if carbon sequestration or retirement might be better choices.

What to plant – tree species site suitability

No-one is advocating blanket planting radiata pine. But how can someone new to tree planting work out which exotic or native species best suit their needs, aims and aspirations?

Productive trees are those which survive and thrive under the conditions on a particular site. Maps of tree species site suitability can be built up by looking at the environmental conditions where different species are currently growing, and the trees’ productivity. The factors that come into play include temperature, rainfall, altitude, soil fertility and moisture availability, orientation to the sun, exposure to damaging winds or salt laden sea spray.

Tree species site suitability maps have been developed for the Hawke’s Bay region and show which species, or group of species may be best suited to local conditions.

The maps show −

- Radiata pine could be grown widely with the exception of dry plains and mountain regions

- Eucalypt species are suitable for coastal area, warmer slopes, and the southern Hawke’s Bay

- Cypress species should do well in the northern half of the province and at higher altitudes than eucalypts but they are not suitable for coastal planting

- Coast redwood can tolerate cooler climates but not dry or coastal conditions

- Totara grows in the same areas as coast redwoods but is tolerant of dryer conditions

- Manuka grown for honey production is best on sunny slopes in warmer and coastal regions

- Native species, which originally covered the land, are generally suitable for widespread planting. Management options include permanent carbon forests on steep land and land at high elevations or growing plantation podocarps such as totara or rimu.

- Douglas-fir has not been considered due to its tendency to produce wildings.

Other ecosystem benefits of tree planting

Planting erodible land provides more benefits than just timber. As well as avoided erosion and carbon sequestration, water quality will improve as a result of reduction in nutrients and sediments entering waterways with a flow-on effect to downstream users. Forests can also provide habitats for native species and spaces for recreation.

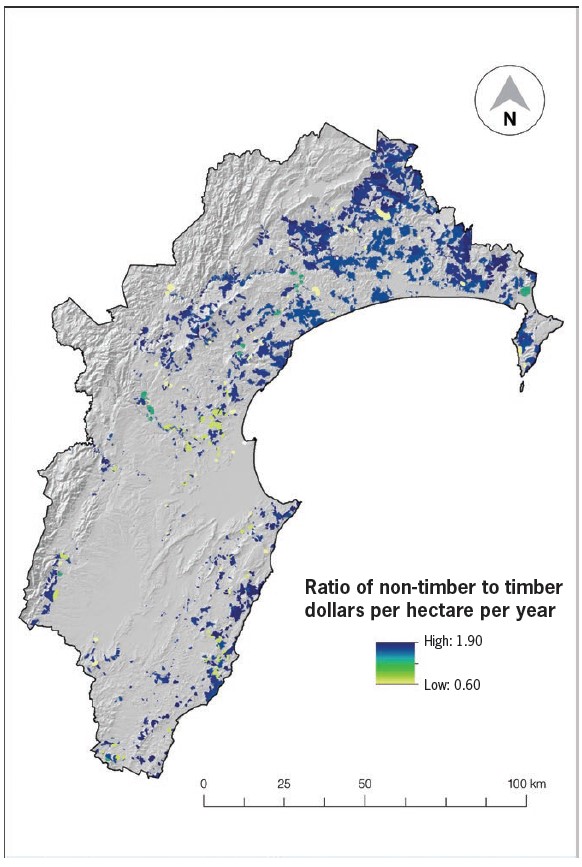

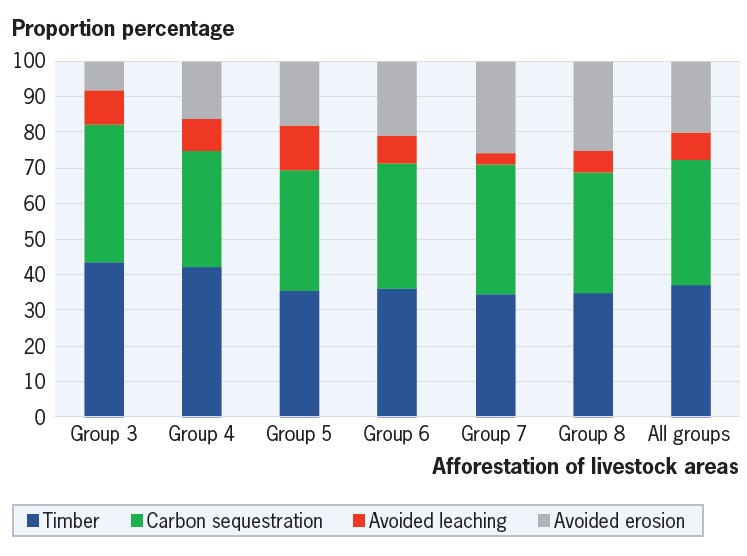

Scion researchers used the Forest Investment Framework to calculate the value of some of these other benefits. The framework combines geographic information system technology and economic valuation techniques to calculate the costs of forest establishment, management, harvest, road and landing development, along with transportation to processors or ports relative to their returns from timber, as well as carbon sequestration. The framework can also calculates the value of avoided erosion including a component that accounts for higher levels of erosion after planting and before canopy closure and values for avoided nutrient leaching.

Putting together the values obtained for timber, carbon sequestration, avoided erosion and nutrient loss across afforestation groupings shows the combined ecosystem service values are at least equal to the timber value, rising to almost twice that on some land classes. An alternative way to express this is that for every dollar in annual profit provided by new radiata pine forests, the value of non-market ecosystem services is at least one and half times greater. The majority of the land identified as suitable for planting to help control erosion is predicted to contribute high non-timber to timber benefits.

The inputs for Forest Investment Framework modelling were based on radiata pine. Data for alternative tree species is needed. It is likely that other species with longer rotations and different growth and carbon uptake rates would provide even greater ecosystems service benefits.

Show us the jobs

Plantation forestry becomes more acceptable in areas where high value processing facilities have been seen to create employment. This goes some way to alleviating the major concern that conversion of farm land into production forests will cause job losses and then loss of local schools, medical facilities and other community amenities.

Considering the Hawke’s Bay, there is considerable scope for increasing radiata pine wood processing in the region. According to Scion specialists, the development of wood processing clusters near Wairoa and Napier could see 1,800 new jobs and nearly $700 million added to the country’s GDP. Energy to power the wood processing clusters could be provided by the slash and waste wood with enough clean energy left over to run freezing works and other local industries, eliminating coal use and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Processing options and market development are also needed if planting alternative species such as coast redwood is to become a realistic option. This includes initial timber processing and supporting secondary processors who make products such as cypress for cladding and outdoor furniture, totara for furniture or carving, eucalypts for flooring, and coast redwood for cladding or to export to the United States.

Jobs are also needed while newly planted trees grow to reach maturity. There are opportunities along the whole forestry supply chain for iwi, cooperatives and other small businesses to get involved with nurseries, site preparation, planting, tending, pruning, thinning, harvesting, transport, primary processing and secondary processing operations.

A continual supply of commercial and native seedlings will be needed for regular afforestation. Only some of this demand will be able to be met by existing nurseries, creating space for new ones. An example of this is the nursery which has been established at Minginui in the central North Island for rearing indigenous trees to regenerate the Whirinaki Forest. The nursery has created jobs and is expected to draw skilled people back to the village. Local businesses working with local landowners is also an alternative to the ‘plant and leave’ behaviour of forestry companies who usually bring in outside workers who move on to the next site once planting, pruning, thinning or harvesting is finished.

Supporting afforestation

Customised solutions for individuals and communities

Tree planting is a land owner decision affected by individual needs and situation. Each part of land or farm is different and land owners need to be able to look at it in detail, such as by using high resolution land inventory mapping. Then they can compare and select areas to improve for grazing, to plant for commercial forestry or perhaps to retire completely to get the best land use mix both economically and environmentally.

There is a natural fear that reducing stocking rates will reduce farm income. However, land owners adopting a more complementary, integrated approach, where less productive land is afforested, they frequently find that they can manage higher quality land more intensively, leading to higher farm returns for livestock. Farm forester Mark Warren reports that, even though he reduced the area farmed for livestock by 25 per cent, because he was able to focus on developing good country he now produces more meat than ever.

Good government

Land owners have long memories and have seen governments, funding schemes and development programmes come and go. They need to see evidence of commitment to long-term decision making and support at regional and national levels. The work carried out for the Hawke’s Bay Regional Council has found there is an opportunity for a central support and guidance mechanism to work alongside land owners to understand their objectives and constraints, and develop long-term plans that fits with the needs and expectations of land owners and communities.

Another part of the puzzle is finance and funding and how it can be used to achieve long term environmental and economic objectives. Land owners are open to a range of solutions when it comes to the commercial side of their activity, such as joint ventures or grants, as long as they fit with their objectives and appetite. Regional and national level planning and investment in market development, wood processing, secondary manufacturing and other application which use biomass such as biofuels is another essential component.

Sharing stories

More sharing knowledge, expertise and success stories is also needed to break down the barriers which discourage land owners from afforestation. Personal experience or knowing those interested in forestry can influence attitudes. This is where owners of small to medium forests come in. They − you − have been there and done that and have some stories to tell.

Mark Warren appreciates this. Having developed a sustainable farming system financially, physically, ecologically and socially, he wants to encourage more farm afforestation by helping others learn from his successes, and his mistakes.

We also need new stories around tree planting, forestry and its role in responsible and sustainable land use to share with the whole country. We need to talk about the full range of benefits of tree planting, emphasising the environmental and social, and the role of trees in creating a more resilient land. The work carried out in the Hawke’s Bay can be repeated around the country to show how the right tree for the right place for the right purpose benefits people, the economy and the environment.

We will not be able to please all the people all of the time. But if as a country we accept that forestry is a part of good land stewardship, we will prosper and become stronger and more resilient.

Michelle Harnett is the science communicator for Scion.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand