Eat your greens, tax is good for you

Howard Moore, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2021.

The following observations and analogies are not meant to be necessarily true, accurate or comprehensive. They are simply an attempt to accept the unpalatable by rationalising the unknowable. This is a skill most of us learned as children when we ate broccoli because − it was good for us. Tax is like broccoli.

When I started writing this in May 2019, over 50,000 teachers were striking over pay and conditions, reports showed there were more homeless people than ever and children had just finished their second march for action on climate change. Almost two years later we are fighting off a global pandemic, essential workers are calling out for better pay and conditions and houses are more unaffordable than ever. Economists agonise over the probable deep, underlying causes such as over-population and the capitalist model. Smaller people like me look for smaller reasons, such as wealth inequality.

Compound interest

It is not new. I am sure some time in prehistory one of our ancestors hit another over the head with a rock in an argument over food or sex. What really gave inequality legs was the invention of compound interest. Like the wheel, this idea took off and the maths of compound interest can be used as a simple illustration of this economic phenomenon.

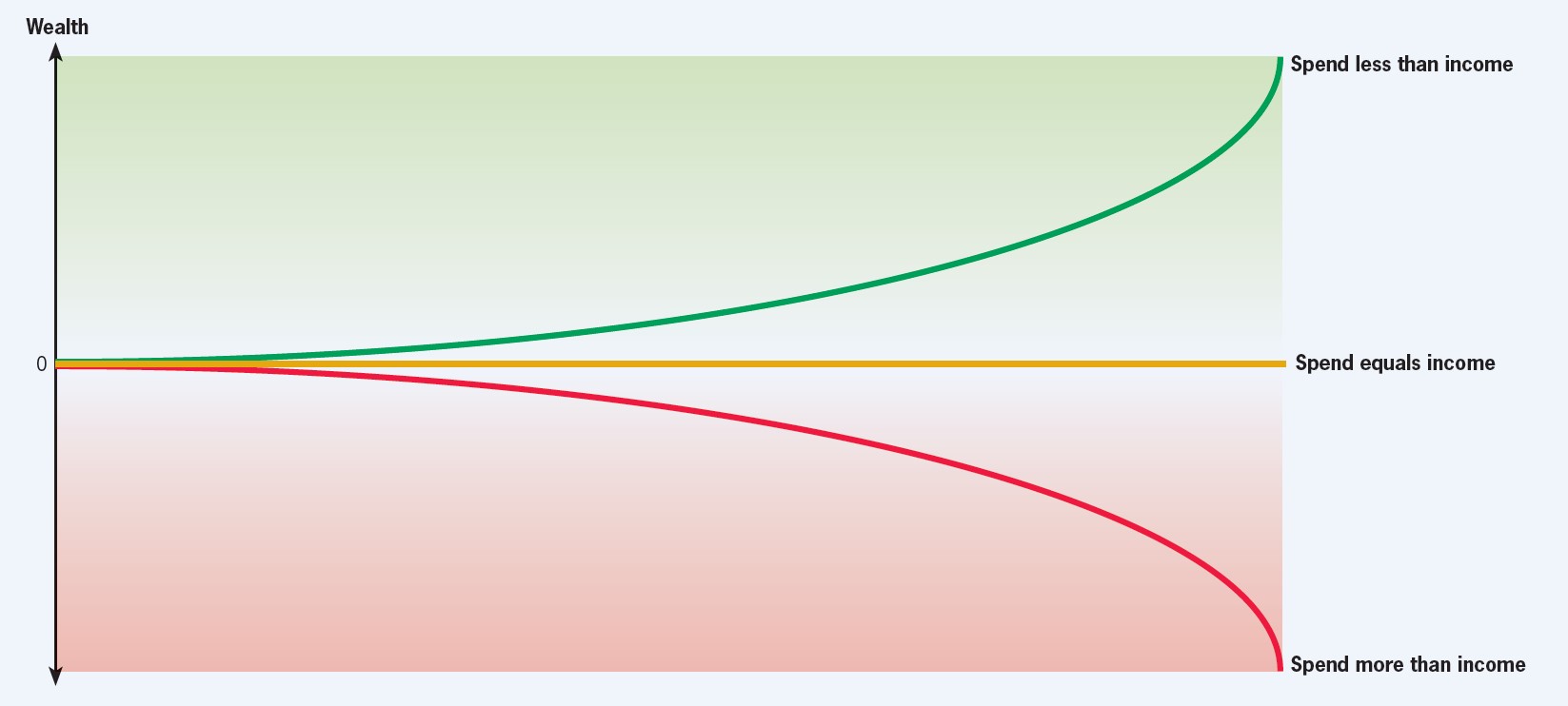

Imagine you earn more than you spend, and your savings grow. Compound interest acts to increase those savings exponentially and you get wealthier. Conversely if you spend more than you earn, you consume your savings and run up debt. Then you are charged compound interest and you spiral into destitution.

This is a positive feedback model. With no damping, you either become mega-rich or you starve and die. Of course, compound interest is not the only thing at play but it serves to illustrate the problem you can see happening around the world. The tragedy is that those above the line who have resources and power generally feel that everyone deserves to be where they are, especially them. Those below the line feel strongly the opposite, but who cares? As Dennis Connor once said after successfully defending the America’s Cup, ‘You’re a loser. Get off the stage.’

Social obligation

As wealth inequality grows it stretches society thinner and thinner until it rips and we get a revolution. They make great movies, but the reality is they always end up in tears and a body count. The rich know these uprisings are inevitable, but can often protect themselves from the worst of it. Indeed, some realise that conflict creates opportunities to seize more wealth.

It is poor people who hold society together. They are not stupid, and they mostly hate revolutions because they provide the body count. Poor people have invented a wide range of things to limit positive feedback, damp the effects of wealth inequality and reduce the likelihood of violence. These dampers do not prevent the rich from getting richer, even poor people aspire to be rich, but they slow the process and so extend the years of peace.

We are so familiar with these dampers that we tend to forget their purpose. They include, of course, tax for the redistribution of wealth for free health care, subsidised education, infrastructure, public transport, welfare, social housing, superannuation, internal security and defence. They include churches, charities, neighbourhood groups, community gardens, friends and whanau. These all act to support and prevent the poor from starving, primarily by taking money off the rich and so reducing their rate of wealth accumulation, but also by the poor sharing with the poor, which is kind but economically ineffective.

Those above the line generally acknowledge some sense of social obligation to support the efforts of churches and charities, but no rich person wants to flat-line their wealth. Usually their charitable donations are managed so that while they live, their wealth continues to accumulate, albeit slower. After all, they deserve to be rich.

Rich get richer

The rate of wealth accumulation around the world has accelerated since the 1980s. Indeed, it is widely believed that most of the money printed and circulated by central banks as quantitative easing after the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 went straight to the rich. Books have been written about the social stresses caused by wealth inequality. Chapter headings include mental illness and drug use, life expectancy, obesity, educational performance, teenage births, violence, imprisonment and punishment. Wealth inequality makes all of these social problems worse.

Right now in New Zealand we cannot afford to pay our teachers and nurses a fair wage, we cannot afford to educate enough doctors to reduce their insane workloads, we cannot afford to build social housing, help the mentally ill, restore water quality and protect our endangered species. There is not enough money flowing through the charity system. So we turn to the government. Where can they get the money? They can borrow it, recover it, print it or tax it.

Borrowing money means asking someone rich to lend it to you at compound interest, which makes the rich even richer. Not smart. User charges once looked like a good idea but as there are many more poor people than rich people they take most of the money from the poor. Not smart.

Printing money creates inflation, which makes many people feel richer even if they are not, brings in more taxes which is good and protects against the evils of deflation which is, er, evil. However, if there is more money in the system it always, sooner or later, ends up in the hands of the rich and so exacerbates the problem.

Taxes

That leaves taxes. Ideally, they would levy solely the rich. Around the world, several wealth taxes have been designed for that purpose. The big problem is that the rich and powerful do not take kindly to such ideas. Remember they generally feel that people deserve to be where they are. If God had wanted them to pay taxes, he would not have invented lawyers and the Double Irish with a Dutch sandwich.

Although rich and powerful people may be few they are, by definition, rich and powerful. They can employ public relations companies and lobbyists and pay for advertisements and rallies to make their point and they generally find ways to carry the public with them. The public − even the poor − often vote with the rich because they are either desperate to believe, or they cannot tell the truth from the noise. In addition, many not-so-rich people who aspire to be rich are not only happy to work on behalf of the wealthy, they also mimic their behaviour. In September 2003 our farmers successfully protested the evils of carbon taxes, and after 17 years they are still mainly exempt from emissions charges.

With New Zealand First in a government coalition, strong opposition from the wealthy along with weak and fragmented support from the powerless, it was politically impossible for the government to introduce a capital gains tax. The Prime Minister has also ruled it out for this term, but strangely enough, that may be quite smart.

Capital gains tax

A capital gains tax is a great idea when asset values are rising because you gain a piece of the action, and while the rich might object they are still getting richer, so no-one is really hurt. When asset values are not rising, it is a dodo. The tax might cost more to run than it earns and it might even have to pay out.

The Tax Working Group recommended a capital gains tax should apply only to capital gains from the date it was introduced. It was not to be retrospective, and there is the rub. Suppose coal mines and thermal power stations become stranded assets. Rising sea levels reduce the value of beachfront properties, freshwater reforms reduce the value of farmland, harvest restrictions reduce the value of forest land, earthquake regulations or working from home reduce the value of commercial office buildings, global pandemics reduce the value of aircraft, hotels and fleets of rental cars.

The future value of billions of dollars of assets is unknown. No government wants to introduce a capital gains tax in a falling market. Without a clear path of rising asset values, frankly, it looks stupid.

A wealth tax based on values rather than capital gains and losses avoids this problem but raises two more. First, who sets the values? Second, if an asset is not earning, how do you pay tax on it? The Greens have tentative answers but they are not easy to find and for the moment, that party has stalled.

Interestingly enough, forest owners are not affected. Forests are not capital, and we already pay tax on their value gains by income tax at harvest. If you cash up your earned carbon credits creating assessable income then you push down your forest land values. Whatever politicians decide to do about a wealth tax, forest owners can relax. But keep an eye out for the revolution.

Howard Moore is a member of the NZFFA Wellington branch.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand