This is free.

Does the Forest Growers’ Levy give value for money?

Stephen Franks, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2024.

Later this year, growers will be asked again to vote whether to continue with the Forest Growers’ Levy. Getting value for money is a vital question to be answered.

No discussion

Before I was invited to be the independent Chair of the Forest Growers’ Levy Trust in 2021, I knew there was a levy, but I had never heard from them before that. I am a small forest grower. I have been growing commercial trees since 1990 but I have not calculated how much the levy would have taken from our sale proceeds. As far as I recall, our forest manager did not report it to us and I do not recall any discussion of it with my fellow investor.

I am currently waiting to harvest around another 80 hectares and I have applied to register an indigenous block for carbon credits.This means I have a large stake in what the levy is for – the profitability of our industry, its pipeline of multi-factor productivity improvements and its social licence to operate.

Why, then, did I and other growers know about the levy, but nothing more? Later in this article I will suggest some reasons. Some are good and some are not. Others are guesses, neither good nor bad. But first, here are some facts.

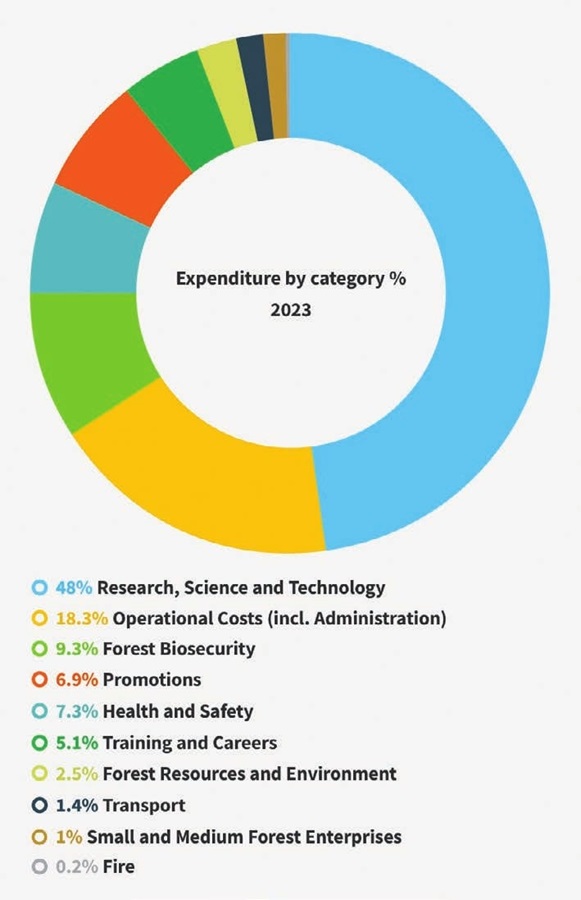

Facts about the Forest Growers’ Levy The levy is charged at 33 cents a tonne of harvested wood as it enters a mill or crosses the wharf.That charge over the last few years has raised between $10 million and $11 million a year.The money is applied in proportions which have altered only gradually over the last three years.They are shown for 2023 in the chart and table on the following page.

Those terse category descriptions do not make it clear that the operational and administrative costs cover a lot of industry communication and liaison. Members of the nine category committees donate their time via their employer. In return they learn from each other and from the projects they must evaluate.The industry generally benefits from speeding the spread of knowledge.

Examples of projects or programmes within the research portfolio include the following.

Tissue culture

The 21st Century Tissue Culture Partnership is a seven-year project by the Forest Growers’ Levy and the Ministry for Business Innovation and Employment. It started in July 2018, building on past investment in breeding and genomics.The project focuses on the efficiency of tissue culture plant production using automated bioreactor and propagation systems.

If successful, the time required to deploy the best genetics from breeding programmes to the forest will be significantly reduced. It will also broaden the selection of improved genotypes which can be propagated efficiently – a pre-requisite for gene editing and other genetic technology.

While the current focus is radiata pine, this technology will also be applicable to other forestry species.The programme will give industry an alternative plan should pathogens or disease affect our commercial forests.

Nursery practice changes

Another programme, the Precision Silviculture Programme, in its second year, aims for practice changes in nursery, planting, pruning and thinning operations.

They will rely on mechanisation and precision advances to reduce the unit costs of recovering thinned biomass and to reduce the labour costs of pruning.

The programme is drawing together remote sensing, terrestrial robotics and geospatial location.

One component is looking at power-assisted tools and battery-operated devices for manual work.This has not yet overcome the difference between the energy density of internal combustion engines and battery longevity.

The project is testing other novel engineering for planting, pruning and thinning, and there are health and safety objectives in some parts of this programme.

Genetic improvements

A specialty wood products programme has achieved genetic improvements for various species, including growth and form for more volume or higher grade, heartwood quality and quantity to produce durable timber, density and stiffness for better structural performance, and pest and disease tolerance. Douglas-fir, a number of eucalypts and a range of cypress hybrids were in the programme. Improvements are starting to flow through to nurseries and tree growers. Improved selections have also been made in redwoods.Tree stocks for growers have more than tripled as a result, reaching 4.1 million in 2022.

An extensive trial network has been established around New Zealand to determine site-species matching where different species will grow best, to understand the effect of climate change as the optimum location varies as climate varies, and to provide a demonstration resource. New products have been developed which are ready to be commercialised including optimised engineered lumber, cross laminated Douglas-fir timber proved to match radiata pine cross laminated timber, thermally modified timber for increased durability without chemical additives, laminated veneer lumber where eucalypt veneers prove to be stiffer than radiata, and timber flooring made from trees grown for pulp.

Do we get value for money?

The Forest Growers’ Levy Trust must now include in its audited annual report what is called a ‘Statement of service performance’. In brief, we need to measure success or failure on what we spend levy money on.

Are we just doing things which seem a good idea, or are we actually achieving well defined purposes? Those questions should be asked about all spending of other peoples’ money. It has always been relevant, but now we ask grant applicants to propose explicit success or failure measures for almost all applications.

Asking the right questions takes us forward, but it does not mean that we will always know if we have succeeded or failed. As has been said many times about advertising – we know that half the money will be wasted, we just do not know in advance which half. It is even harder than that. Often we will never know, even afterwards, what advocacy spend and effort has worked, and what has not.The vagueness of the term social licence tells us a lot. No one may know even afterwards, what factors in a large range were most influential on public perceptions. Even asking people is not reliable.

They often respond with what they think most people would say.

For example, forestry could suffer a media push like the ‘dirty dairying’ campaign. It could result in sustained pressure for politicians to impose new taxes or consenting burdens for harvesting, or to limit planting. Another scenario could see our contribution to climate change protection secure for forestry the kind of free pass that has served the film and wine industries well.

On almost all public issues there will be multiple theories about what could have been said or done differently. People in regions where 50 Shades of Green has been active may feel there could have been more focus on combatting its misrepresentation.Those where flood-borne slash has damaged assets may consider we should have spent more on countering misinformation on the sources of slash. Others might argue, again with some research justification, that the more oxygen we give to some of these concerns, the more trouble we will attract because there is not enough media appetite for facts. Outside the public advocacy area the we receive few complaints about funding decisions.

Reasons for lack of knowledge

Among the good reasons for growers not hearing or caring much about the Forest Growers’ Levy may be –

- Those who know about the projects and activities funded by the levy are broadly satisfied.

- No one pays the levy until they harvest.We are all price takers. Harvest returns bounce around uncontrollably, so we may be insensitive to small costs at that time.

- Since the levy began with an industry vote in favour in 2013 it has not been controversial, and without controversy there will be little public reporting.

- The vote was overwhelmingly for renewing the levy permission in 2019.

- Fortunately, we have few issues where people see sustained conflicts of interest within the industry. Collective industry-good levies are common here and in Australia. Some industries abandon their levies after bitter fights over who controls the levy spend

- The Forest Growers’ Levy Trust Board membership is well spread to represent the views that might divide us.There are of course differences in opinions, and priorities change over time. However, we have kept a broad consensus on the industry-good priorities.

- There is efficient specialisation in our industry. Many growers of small forests have their forests, or at least their harvests, managed by contracted experts. They handle the transactions so owners never see levy invoices. Even if the levy amounts are easily ascertained owners pay attention only to the nett receipt for harvested logs.

Reasons to not know

An undesirable reason why growers may not know much about the projects funded by the levy is that we are unable to tell them.

- The Forest Growers’ Levy Board does not have contact addresses for many levy payers.

- Log owners are often invoiced through their agents who send logs to the mill or the port and agents do not necessarily disclose their principals.

- Forest managers we can contact may not bother to pass on the Forest Growers’ Levy Trust communication sent to them for that purpose.They may think that forest owners will not be interested.

- We can search land registry information for what appears to be forest land but most of it is not commercial for harvest. Even narrowing the search down would not necessarily provide useful contact addresses. A company or individual name can front for many beneficiaries.

- The Privacy Act is an obstacle.

Contacting others who benefit

We will need to contact as many forest owners as we reasonably can this year, about the industry vote on whether to renew the levy for another six years.Work funded by the levy benefits the owners of carbon forests and other trees which may never go to a mill.We cannot confine to levy payers the benefit of our work in bio- security or tree root nutrition, or fire and resilience to drought. In fairness carbon forest owners should be contributors to at least some levy projects.This year one of our projects is for a more comprehensive mailing list of forest owners.

Other explanations for the lack of pressure from growers for more direct communication have included –

- The levy amount is genuinely immaterial in context. After growers have spent 25 to 30 years incurring costs without income, the one-off levy amount is not significant. If growers feel that those deciding on the industry-good projects have our collective interests at heart, few growers will spend valuable time second guessing the decisions.

- The decisions of the Forest Growers’ Levy Trust Board are reasonably transparent and we report on the projects funded on our website.

- People know that one of the reasons for collective funding of projects is to share the risks of failure. They accept that we will take on uncertain projects if there could be a substantial industry upside.

- It is rational for most growers to get a free ride on supervision of levy spending.The owners of large forests represented on the Board have most at stake, so as payers and as early adopters of the results of research and other products of levy spending, they put expert time into supervision

- Voter apathy and satisfaction can go together.There appears to be comfort from the knowledge that growers can eject Board members if they cease to serve growers.

The upcoming referendum and meetings in preparation will allow growers who are interested to say whether they think they are getting value for their levy money.

Stephen Franks is the Chair of the Forest Growers’ Levy Trust.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand