Log value recovery in a woodlot context

Andy Dick, New Zealand Tree Grower May 2005.

Commercial forest owners and forestry research organisations have over the years attempted to maximise returns by developing tools, processes and disciplines called log value recovery.

If you have a good understanding of the potential log value standing in your forest, then it is a reasonable expectation of the forest owner that this standing value is translated into the logs produced during harvesting and marketing. So if pre-harvest assessment is the method by which forest and woodlot owners value their estate, then log value recovery is the process of turning the standing value into bankable reality.

Dollars per cubic metre

Log value recovery relates to extracting the optimal log value from a harvesting operation, given the marketing constraints and opportunities of the day. It is best measured as a ratio of dollars per cubic metre of logs extracted and sold against the dollars per cubic metre estimated to be standing in the forest before the start of harvest.

Optimal value recovery is only obtainable with difficulty. The chase for value recovery can only occur from the use of accurate and appropriate data measurement.

Accurate description

The first stage in value recovery is an accurate description of the forest resource in volume and merchantability terms. The techniques, merchandising calculations along with the taper and volume functions used for radiata woodlots, linked with accurate mapping, allow such descriptions to be obtained. Improvements in this field are gaining momentum. A number of trials over the years have endorsed the accuracy of log prediction. The most fundamental requirement of a commercial forest owner, outside of sustainability and health requirements, is to maximise the financial return. As Stuart Orme reinforced recently – you cannot manage that which you cannot measure. So it is with forest value and value recovery.

The final payout

From the start of the harvest, a number of factors determine the final payout to the woodlot owner –

- Log markets – proximity to them, accessibility and the price paid by grade

- Cost of harvest and transport

- Infrastructure and the cost of establishing and maintenance

- The quality and quantity of the trees being harvested and the methods used to convert the trees into logs.

In considering the last point first, it is useful to describe the quality and quantity of logs extracted using a butchery analogy. Consider a mature tree as a cattle beast destined for home kill. Ultimately, the cattle owner wants the butcher to bone out as much meat as possible.

Similarly the woodlot owner wants to see the most merchantable amount of wood as possible cut from the trees.

More importantly, you want to maximise the proportion of choice cuts extracted from the carcass – as much fillet and sirloin as possible, but obviously you cannot turn offal into fillet. It is similar for the woodlot owners. They want all the top quality wood possible to be produced and the minimum of volume to end up as pulp. In the final analysis the tree owner wants the greatest return in dollar terms. The use of optimising technology can ensure this will happen.

The weight of wood

The actions of the harvesting contractor, and how he is rewarded and managed, is critical to extracting value from the woodlot. In most instances, harvesters are paid on the weight of wood produced. This is understandable given the universality of truck scaling and the simplicity of weight as a measure. However, this system creates an obvious clash between the needs of the contractor and the woodlot owner.

The contractor, to maximise his earnings, wants to produce and load out as many tonnes of logs as possible. To him a tonne of pulp generates the same revenue as a tonne of pruned logs. While most professional loggers are exactly that, professional and behave accordingly, there is no getting around the fact that payment on a weight basis is no incentive to ensure the maximum extraction of more valuable logs. Ways of mitigating the effect of contractors pursuing tonnes, rather than emphasising value, is to change the way they are paid, such as differential payments. Another is to remove the critical log making phase of harvesting from contractor control.

Gaining value

Value is gained at the harvesting phase and the following must be measured and monitored –

- Cutting the broadest range of log grades available that cover the value spectrum. Accumulation rates are monitored – if you can collect a transportable bay within a week of production, cut it.

- Training and coaching of fallers and extractors to ensure stump.

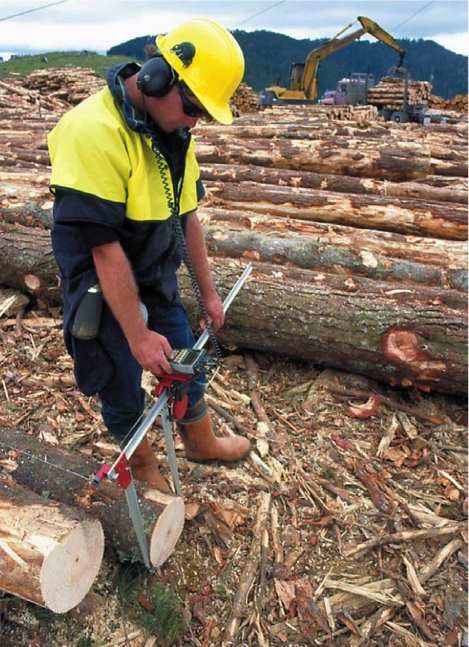

- Log making to maximise the relative on-truck value of each stem. This can only be reliably achieved by electronic optimising.

- Ensuring that loader operators do not top up lower value loads with higher value grades.

- Ensuring that log makers are sufficiently trained to cut logs well and know individual customer specifications.

- Making sure that landings are configured to allow the critical log making phase to occur unhindered and with sufficient storage space for a range of grades. Transport of logs from the landing should be managed so that grades are regularly removed and storage space freed.

Value recovery principles

Without market breadth, value recovery is difficult. When valuing your forest ensure that the cutting strategy used to asses the value of the resource about to be harvested reflects the range of the markets available within your district. When considering market breadth you also want markets to be open to you for the duration of the harvest of your block, particularly for the high value grade of logs.

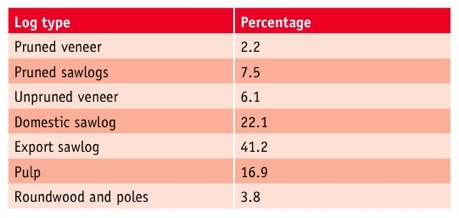

The table below represents the proportion of log grades that were produced in a commercial forest plantation in the central North Island across a two-year period that applied the value recovery principles listed above. Optimising technology was used to ensure that every stem harvested returned the best value possible to the forest owner. The point here, as it relates to market breadth, is the proportion of post and poles produced. Most districts have a post and pole yard. The alternative market for this material is pulp at about 60% of the roundwood value. It is worth the effort for the woodlot owner to produce roundwood even though it is an inconvenient grade for the harvester to produce. Many loggers and stumpage owners do not apply these grades to their cut plans.

There are alternatives to a value recovery approach to harvesting for larger forest owners compelled to return the standing value they have assessed within their forest. One method is to try and achieve market domination so that mills are forced to pay a premium to access limited localised log supply, and where sufficient competition exists, to ensure that top dollar is with forests harvested and marketed as cheaply as possible.

For the woodlot owner these options do not apply. They cannot dictate the price of their logs, and they do not have the continuity of work that allows them to negotiate cheaper transport and harvest rates. The competition to buy their woodlot depends on the market conditions of the day and the current strategy of the woodlot purchasers operating in their district.

Maximise the financial return

Cost control in a harvesting context can be a sad exercise of squeezing contractors that are trying to survive at a time of reduced harvesting capacity. It is invariably counter-productive to maximise your gains from a valuable forest or woodlot, and is an exercise that compromises the people that are most crucial to converting your trees to value.

The target for the harvest and log sale process for any forest, large or small, is to maximise the financial return without compromising safety or the environment. A focus on cheap logging is a poor alternative.

Sound judgments

In my experience, most woodlot owners are sufficiently knowledgeable to understand the basics of forestry. Coupled with canny business prudence and word of mouth, they make sound judgments as to whom they appoint to harvest their forests.

However, other than using a competitive process to ensure they get a good price for their woodlot, the woodlot owner will not get best value recovery practice. They will usually get served up an offer that mitigates the harvesters or the woodlot buyer’s risk. In this mechanism the woodlot purchaser and harvester guarantees a price per tonne of a particular grade produced. There will be no guarantees of the proportion of high quality log produced despite the proportion of high quality projected in the forest. In essence, the purchaser will be getting his margin on tonnes produced just like the harvesting contractor.

Woodlot owners should insist on lump sum payments wherever possible. This method of payment ensures that the purchaser has to research the standing value of the forest and then put in place the right mechanisms to ensure that value, not just tonnes, are produced.

Ask some questions

The next time you sell a parcel of forest ask the following of your tree agent or corporate wood lot buyer –

- What volume and grade mix was there? For any sizeable woodlot purchase all buyers will have this information at their fingertips.

- What grade mix and what markets do you have?

- Were appropriate conversion factors used in assessing the grade within the standing forest, particularly if a large number of cuts are export grades?

- What system are you using? Are you log-making to priority or value? Are optimisers being used? If log-making is mechanical, then advantages in safety and production will be offset against reduced value recovery.

Traditional harvesting and marketing practice in New Zealand under-delivers on realisable standing value by up to 20%. Systems and processes exist that reduce this value recovery gap to the benefit of the forest owner.

Andy Dick is a NZIF Registered consultant specialising in log value recovery.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand