Trees combat erosion and protect stock

Mike Halliday, New Zealand Tree Grower May 2008.

Continuing our series of articles profiling the farm forestry model in action. We present here a case study showing another practical example of how trees can be integrated into the working farm landscape for truly sustainable land management.

Raumati is a 460-hectare property at Patoka on the southeastern edge of the Taupo Ash country in western Hawke’s Bay. It is best described as rolling hill country with deep intersecting gorges. The property is 350 metres above sea level, and considered summer-safe, with mostly an evenly spread 1,500 mm of rainfall a year. However it can be subject to substantial rainfall from sub-tropical lows and receive summer rainfall from damp, south-easterly, anti-cyclonic flows. Snow is not uncommon, with periodic heavy falls.

The light ash soils are subject to both gully and tunnel erosion, with some wind erosion on exposed ridges and faces, especially in sheep camps and following cultivation. There has been moderate slippage on steeper slopes.

Three generations

Raumati was sold in 2005, having formerly been in the Halliday family for three generations. It was purchased in 1936 after eight years of managing the property. Gorge fencing began in the 1930s for stock safety, and tree planting began in earnest in the 1950s. In the early 1960s a plan was developed with the Hawke’s Bay Catchment Board, and planting of alternative species such as eucalypts, Douglas fir, and redwood on gorge edges was undertaken, along with various willow and poplar plantings. In the early 1990s up to 50 hectares of gorge was placed in a QE II covenant.

Following the poplar rust of the early 1970s, the Catchment Board plan was revisited, and extensive gully plantings of willow and newer poplar clones were carried out during the 1980s. These plantings became valuable fodder reserves during the El Nino droughts of the 1980s and 1990s, also eliminating the habitat of liverfluke in snails. It has also been observed, although not properly quantified, that the shade available from these plantings has decreased the amount of water consumed by livestock during summer heat.

Shelterbelts

A system of shelterbelts was also put in place, generally following the pattern of a row of slow growing species on the windward side and faster growing on the lee side for north-south belts, and poplar or Italian alder for east-west. This shelter has enhanced both pasture and livestock performance.

New opportunities

Like the rest of New Zealand, aerial topdressing opened up a whole new production opportunity for Raumati in the 1950s. While small aircraft that could follow gorges and contours were being used this proved to be very successful. However with the advent of bigger, faster aircraft, accuracy declined markedly, leading to extremely variable phosphate levels.

A decision was made to move to ground spreading, with inaccessible generally erosion prone areas retired for planting. Pasture renewal and fodder crops had been abandoned in the 1970s due to incidents of wind blow and weed problems. However with improvements in direct drilling methods, a programme of repasturing using new improved varieties recommenced in the mid 1990s. It has become quite clear that on these types of soil cultivation is no longer necessary, or in fact, desirable.

Productivity increases

All the factors mentioned in the previous paragraphs, along with the addition of improved livestock genetics, led to a marked increase in productivity from the late 1990s. Some of this could be put down to the fact that with gorge fencing completed, an original sheep to cattle ratio of 80 to 20 altered dramatically to around 55 to 45.

An initial goal of 150% lambing by the year 2000 was met in 2001, with a target lamb slaughter weight of 17kg. Likewise calving percentages reached the mid to high nineties, with steers averaging 700 grams per day live weight gains for up to 15 months when they were sold.

There is no doubt that the provision of shelter from the cold southwest winds in spring allowed for an earlier growing season and a longer period of compensatory growth for several weeks. In addition there were improved conception rates in the cows. Soil temperatures were measured following the cold south-westerly rain that broke the 2007 drought. They were between half a degree and one-and-a-half degrees warmer in the lee of shelterbelts up to five tree heights into the paddock than those in non sheltered areas.

Woodlots have provided an important role for shelter after shearing over many years, especially with the advent of winter shearing. The use of a cover comb and three to four days in a woodlot straight off the shears proved an invaluable management tool. However bush mustering skills were tested in the 14 hectare block. The areas of the farm with shelterbelts also provided ideal lambing areas for ewes expecting multiple lambs.

Harvesting radiata blocks

Several small blocks of radiata were planted in unproductive and at-risk areas from the 1970s onwards initially under the Forestry Encouragement Grant scheme. Originally these were managed under a conservative Forest Service type of regime, but as the challenges of planting on more fertile sites became apparent, adaptations needed to be made regarding the timing of silviculture and stocking rates.

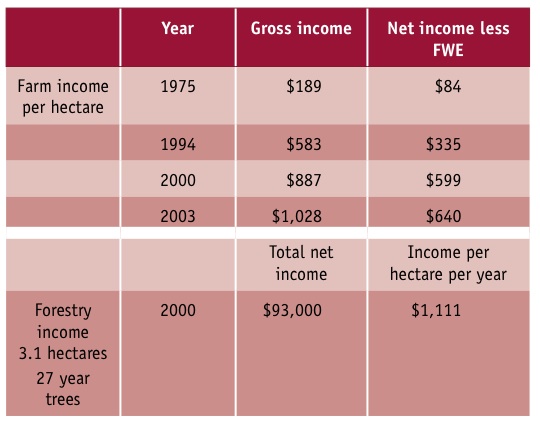

The first harvest of one of these managed blocks took place in 2000, and a comparison of the income from that harvest with some snapshot farm incomes during the rotation of the woodlot, can be seen in the table below.

It should be remembered that this income comes on top of the accrued benefits of trees on farms mentioned previously, and compares forestry income net of harvesting and transport costs.

The harvest was so successful that the original stocked area was doubled, ironically forming a six hectare woodlot that is half pre-1990 and half post-1990 forest. One wonders if anyone from the climate change office will be able to tell the difference come 2030.

With the considerable cash injection for the farm from this exercise, around $70,000 was spent on an improved water reticulation scheme. This allowed for closing off more wet and at risk areas that could be planted and used for nutrient sinks, which have become beneficial as subdivision and intensification increases.

On the sale of the property, forest rights on different woodlots have been retained to varying degrees. The remaining 1970s plantings were harvested in 2007 with very similar financial results to those of 2000.

The planting stock

The 1970s planting stock was nothing very special at all, probably the most improved being labelled seed orchard stock. This block was the first to receive a release spray – Paraquat and Simizine – the same mix as the lucerne paddock next door. During the 1990s we moved up the GF ratings as far as GF25 cuttings. The year 2000 replant was done with GF+ WD30 cuttings. In 1995 a 14 hectare block that had been developed from scrub 25 years previously and was showing signs of all three types of erosion was planted out in a joint venture with other family members.

The next story

Upon selling the farm we bought a section at Kuratau at the south western end of Lake Taupo. We are in the process of building using timber milled from Raumati. The framing is Douglas fir from the original 1959 planting, the board and batten radiata from a 1956 planting, some redwood sarking from a 1960s planting. The story of this exercise may well find its way into print some day.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand