Fire management for small forests

Gary Lockyer, New Zealand Tree Grower May 2012.

Small forests are considered to be anything from a few trees to over 1,000 hectares. Whether you own or manage an exotic or indigenous forest, protecting it from fire is critical to making sure that you get the full value for your trees. The guidelines in this article should help reduce the chances of a fire, and show you how to prepare for one should it occur. The information is set out in five parts −

- Preventing forest fires

- If a fire starts

- Preparing for fire

- Managing the risks

- Insurance

- Electricity, forests and vegetation.

Preventing forest fires

The common fire sites:

- North-facing sites which the sun warms and dries both ground and vegetation much faster than southern faces

- Sites with higher temperatures dry out faster than cooler wetter areas and so have more fuel available

- Land with lower relative humidity where a fire burns more vigorously, so these sites are at risk in dry weather, even cold sites such as high altitude hill country

- If fire starts on windy sites it will spread faster, cause more damage and be harder to put out than at calmer sites

- Sites well hidden from public view with good road access are favoured for burning out stolen motor vehicles or working on illegal activities such as growing cannabis.

Select less burnable species

Nearly all woody tree species will burn. Even trees which are reluctant burners may catch fire if the understory is full of plants that burn well. To reduce the risk, consider controlling the understory weeds. As the diagram below shows, a lot of exotic species burn more readily than many native species.

You can reduce your risk by planting a buffer of less easily burned native species around your trees. This buffer zone should be 10 to 20 metres wide against road edges or vulnerable boundaries. Clear any gorse near or under your trees and keep it cleared. Also when planting your forest, choose species which have a lower burning risk.

Manage your forest to reduce risk

The way that you look after your forest and the season can increase or reduce the risk of a fire. For example, if you thin trees in autumn you reduce the risk, but if you do this in summer you increase it. Broadcasting fertiliser in a very young forest will cause weeds and grass to grow vigorously, increasing the amount of fuel available. Applying fertiliser to each tree will promote tree growth rather than weed growth.

Reduce your risk by considering the amount of available fuel resulting from any management operation, and plan the timing or method to reduce or remove it. Prune trees close

to road edges so that fires cannot use weeds on verges to travel through the trees. Stop mechanical operations when fire danger is extreme or very high.

Discourage illegal activities

People start most fires. Try to prevent controlled burns from escaping and carefully manage machinery operation, recreational use and other potentially harmful activities in your forest.

Make it difficult to park and burn a stolen vehicle, to use your land for drug cultivation or to deliberately set a fire. Improve property security by limiting trespassers and perhaps encouraging approved access. Locking gates or barriers such as drains, putting concrete blocks or large trees across entry points will limit vehicles and reduce fire opportunities for vandals. In addition encourage sensible people to visit your land. Use the Trespass Act if necessary.

Have sound gates, fences or barriers and minimise the amount of gorse. It is good to have friendly, responsible and cooperative neighbours so consider being part of a Neighbourhood Watch group.

Controlled burns

About 20 per cent of wild fires are managed fires that have escaped. If you or your neighbours are burning-off, ensure that the burn is under complete control at all times. Before starting a controlled burn establish fire breaks and ask for advice from your local Fire Authority.

Check the long-range weather forecasts and fire season status. If the fire season status is restricted, get a fire permit from your Fire Authority and ensure you comply with any special conditions on the permit. Tell all the neighbours what you are planning and select a suitable time of day when conditions are less severe.

Operate machinery safely

When machinery is being used in your forest ensure that bulldozers, excavators or trucks are well maintained and have suitable fire extinguishers on board. The machines should be clean and have no oil or fuel leak and should be turbo-charged or fitted with a spark arrester − turbo-charged engines do not emit as many large cinders as other engines. The radiators should be clear of grass and fine twigs and bulldozer belly pans should be clean – clear any sump oil, fine twigs and branches.

Exhausts on all plant engines should not be directed towards fine dry fuels nearby. Make sure that contracts specify the exhausts port is in accordance with Forest and Rural Fire Regulation 2005, Regulation 55 as a minimum. Machines should have self-activating fire extinguishers, if possible.

Chainsaws should be fitted with spark arresters that trap or pulverise exhaust carbon particles. Work the saw at cooler times of the day in early morning or late afternoon. Halt operations if exhaust gases cause fine fuels to smoulder. Clear all flammable material away from each saw cut and check for smouldering embers before moving to the next cut. Cool the saw before refuelling and refuel in a place free of combustible fuel. Clean spilt fuel from the engine before starting.

People using disc grinders or welding need to have suitable water supplies readily available at short notice, and a written authority from the forest owner. Work should be done in open areas and not too close to dry fuels such as browned-off grass or eucalypts. A fire permit may even be required.

Ensure recreational users behave safely

Discourage recreational use during extreme fire danger. Instruct all children living in or visiting the forest area about fire safety. Gas-powered cooking stoves should be used rather than thermettes. Also discourage irresponsible behaviour such as four-wheel drive and motorcycle rallies in the forest without proper exhaust systems on vehicles.

Discourage using an open flame anywhere near trees. This includes matches, fireworks, bonfires and blow-torches. Also discourage the use of firearms using tracer ammunition or with coarse-grained gunpowder. It is particularly important where there is long, dry grass and steep slopes on northerly aspects.

Do your housekeeping

Manage the site by planting or clearing fire breaks, avoiding fuel continuity and keeping the understory clear of flammable material. Create firebreaks by planting forest edges with species that do not burn well, discing soil or creating an access road. Firebreaks are best constructed on ridgelines or property boundaries.

Clear pruning and thinning slash from roadsides and prune lower branches so that the fire has no fuel to climb into the trees. Keep weeds down on the forest margins – grazing can help although you need to make sure that your trees are not browse vulnerable. Less combustible plants, such as clover which are often found on the side of the road, also make effective fuel breaks.

Also avoid spilt oil and fuel. Do not dump fuel or grease containers. Remove or bury rubbish, including derelict cars and old plastic, paper or wood containers. A forest property that looks untidy is a more likely to be target for arsonists than a well-kept and well-managed one.

Avoid possible ignition points

Keep vegetation clear of power lines. Fires can start if branches contact wires or wires contact one another to drop molten aluminium into dry vegetation. Check with your local electricity authority if you have any doubt.

If you are having any tracks being constructed make sure that the operator knows of any gas pipelines that may be underneath and to contact the pipeline owner. Avoid planting on sites where there may be pockets of natural gas as these can seep into the earth’s surface and ignite. Several such sites are known in the eastern North Island.

Spontaneous combustion can occur on sites where plenty of volatile fuels or finer fuels are present or buried such as hay barns, wood processor sites at skids or landings. For example, reduce the amount of foliage and light branches at the skid sites by putting it all back into the forest. Make sure that steel ropes are not buried near fine fuels. Do not use explosives in elevated fire danger periods.

Tin lids or other reflective surfaces might act as magnifying glasses and start fires. Phosphorus bait can be laid on an overturned earth sod instead of a tin lid and later buried under the replaced sod, or alternative poisons can be used. Keep the site clean of bottles and other reflective items.

Lightning strikes can happen in warm, dry weather with the passage of cold fronts. While there is nothing to stop lightning from starting a fire, some of the ideas above will help to reduce the amount of fuel, and limit the seriousness of the fire.

If a fire starts

You should telephone 111 immediately as large fires were once very small fires.To comply with the law the following applies −

Any person not engaged in essential services who becomes aware of an unattended fire burning in the open air, in a forest area, or during a restricted or prohibited fire season, shall cease work and do everything within his/her power to extinguish the fire. If the person finds that they are unable to extinguish the fire, they shall notify the nearest available fire officer of the outbreak.

For practical purposes this means that if you cannot put the fire out, telephone 111 and notify your Fire Authority. You must tell them −

- Your name, rapid number, telephone contact number and where the fire is located. You may have to spell some place names. A pre-arranged New Zealand map (Topo 50 series grid reference for your forest) could help

- What is burning, and if you know the name, which Fire Authority has to deal with it

- The approximate extent of the fire in hectares and the type of terrain in which the fire is burning

- The closest brigade or volunteer rural fire force which is available to deal with the fire

- The quickest route and the quickest roads for fire-fighters to take to get to the fire.

Once you have provided this information you may wish to advise your neighbours if they are likely to be affected and to mark access routes for incoming fire vehicles, if this is necessary, through whichever gate is closest and safest. Use bright-coloured spray paint writing the word ‘fire’ with an arrow pointing in the direction of the access gate. Mark suitable water supplies and access to these in the same method as above.

If fire fighting involves using helicopters, identify any aerial hazards and mark or eliminate them. Fell trees on the entrance or exit flight path if it is on your property and identify any wires strung across gullies. Establish helicopter water points upwind of the fires, and away from dense smoke or ember fall-outs. Move livestock that may be affected by fire or smoke. Use the fire response schedule, as illustrated later

in this article, to make a similar template for your forest to be sent to the local Fire Authority, neighbours and first response fire crews.

Preparing for fire

A gram of prevention is worth a kilogram of cure as far as forest fires are concerned. If a fire starts, it must be put out as soon as possible before it spreads. You can help this to happen by preparing well in advance. Ensure easy site access, install good signage and have adequate water accessible.

Easy access

Make sure that fire-fighting equipment can get on to your land. Road surfaces must not be undermined or have deep ruts cut by water. Long, dry grass over steeper roads reduces traction and makes access dangerous. Compacted gravel road surfaces provide better grip than recently dozed moist surfaces or grass.You will need at least light truck access. This requires −

- A road width of four metres with vegetation cut back to this width

- Road grades no greater than one in four

- Bridges capable of taking 2.5 tonnes laden weight

- Turning areas of up to five metres must be available for a multi-point turn.

If you lack access to water or have a serious fire risk you will need large truck access. This means you need −

- A road width of four metres with vegetation cut back to this width and a height limit of no less than 3.4 metres

- Road grades no greater than one in five

- Bridges capable of taking 44 tonnes laden weight which is what a transporter carrying a larger bulldozer could weigh

- Turning areas of 12 metres for a multi-point turn.

Some private rural roads and bridges are not constructed to the same standards as public ones. If in doubt, check before a vehicle gets stuck.

Good signage

Fire-fighters need to know where to go. Have signs at entrance points and property boundaries. These are helpful and distinguish one property from another. Rapid numbers also need to be prominent to identify the property when a fire is reported.

Have signs for bridge weight limits, water point access and places where there are hazards that may not be known to strangers entering the property such as agrichemicals, fuel and electricity. Many of the signs you require can be purchased from industrial safety shops.

Adequate water

Water points should be easily accessible and clearly marked. They could include streams, rivers, ponds, dams or tanks. Mark the major supplies of all-year-round water. Ensure that −

- Vehicles can access the water

- Safe aircraft landing points are no more than 50 metres away from the supply point

- Water points are well situated around a forest and ideally helicopter water sources should be within two minutes flying time of any part of the forest

- The available water volume is sufficient to supply pumpable water at 30 litres a second to fill numerous tankers, many large monsoon buckets and hoses. A young forest may have adequate water now, but not in 10 years if the trees have drawn it all up for growth

- The available water volume is greater in areas that are drier more often or have severe droughts.

Larger capacity water points can ideally be located outside the forest area. Rubber-lined dams are useful for providing water at high points. Fence these off, as stock will drink from them and hooves destroy the liners. If a dam is made, the regional council may need to be consulted before to construction, depending on water volume held or catchment area.

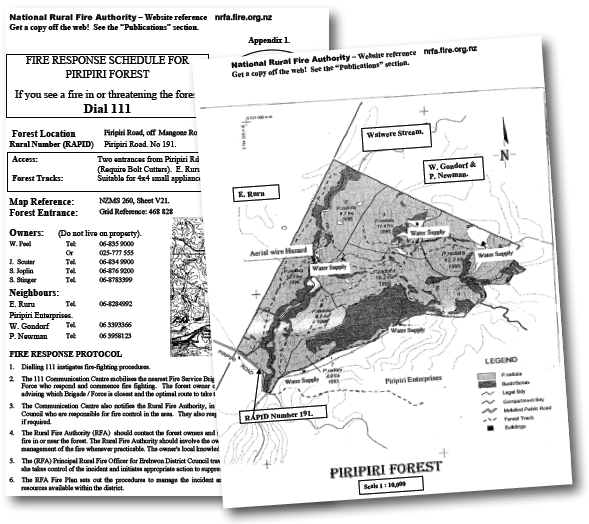

Fire response schedule

You can also prepare for fire by having a fire response schedule like the one illustrated. Include all the details for your land and forest and distribute it to your Rural Fire Authority and helpful neighbours.

Equipment for fighting smaller fires

If you intend to deal with a smaller fire yourself, you will need suitable clothing and hardware. Safety is extremely important in fire-fighting. Synthetic clothing melts if exposed to radiant or direct heat. This can happen even under a layer of cotton or wool. Natural fibres are better for fire-fighting. Leather gloves and sturdy footwear are a must.

People with bare feet or jandals should not be allowed on to the fire ground, so send them out of danger. Hard hats or woollen balaclava, eye protection, first aid kits and clean drinking water are also necessities for fire-fighting. If a forest owner has any doubts about fighting the fire, leave it to the Rural Fire Authority.

Knapsack water sprayers are cost-effective on smaller fires. Larger or more extensive forest fires require specialised equipment and numerous people. Find out the everyday telephone number of the Rural Fire Authority beforehand. Improve your chances of putting the fire out by −

- Ensuring easy access, good signage and plenty of water

- Having suitable clothing available before a fire

- Having suitable fire-fighting equipment to effectively deal with a small fire

Calling 111 to help before any fire gets too large.

Managing the risks

A forest owner can minimise the risks and consequences of fire by effective use of neighbours, contractors and insurance. A local community working in your favour is a great asset. Supportive neighbours are especially important when the forest owner is an absentee owner. Notifications of fire problems are more likely from good neighbours than official agencies. Forest owners should encourage a strong, watchful and helpful local community. They need to be part of the community and support if it they expect support in return. The local community is likely to be a first responder to any wildfire on the property

Contractors work in many small forests doing a wide range of work.Their contracts should specify conditions for the safety of others, themselves and the forest. This is especially so with operators of heavy machinery and chainsaws. A sample schedule is available on the National Fire Authority website. Before the contractor is allowed on to the property to begin work, ask to see evidence of sufficient and appropriate insurance cover as well as a current paid-up premium.

Insurance

Insurance gives forest owners some security so that a fire does not mean needing to sell other assets such as your home to pay for fire suppression costs or other losses caused by a fire starting on your property. The property found to be the point of origin for the fire is a likely target for lawsuits from people suffering losses.

For example, a fire originating in your exotic commercial forest and spreading to a larger commercial forest will have the other owner attempting to put out the fire. You could be asked to pay for the fire suppression cost as well as your neighbour’s forest losses.

You are more likely to require larger insurance in warm, dry localities with strong summer winds and many people close by or using the forest illegally. Think about your forest’s risks before you insure. Higher fire risk situations for a forest include −

- Remote, dry roadsides with no telephones nearby, no cellphone coverage, plenty of gorse, strong winds and irresponsible neighbours

- Locations close to an urban settlement in an area of low rainfall and summer drought

- Easily accessible tracks, out of view, off public roads that are suitable for burning out cars.

Against these situations must be weighed the likelihood and consequences of fire. In many cases the risk of fire is very low. Here are some examples of lower risk forest fire situations −

- A forest in high rainfall areas and otherwise damp environments

- Forests surrounded by rivers, sea or high standing native vegetation

- Mature forests with bare earth in the understory and close to significant permanently available fire suppression resources

- Remote forests with a low history of fire occurrence.

If your forest is next to a larger one you need to consider a higher level of fire suppression insurance and public liability insurance. Some contractors will assure a forest owner that they have insurance cover but they do not, or it has lapsed from non-payment of the premium. The result of a contractor not having sufficient and appropriate insurance is that the forest owner could have to make up any differences owing to fire authorities for fire suppression or to others affected if they suffer a loss.

Fire suppression cover of $100,000 would have met all fire expenses in 80 per cent of fires in 2009. Now $2,000,000 will meet almost all fire suppression costs for almost all rural fires. Values of forest loss have ranged up to $2,500,000 in recent years, with additional costs to clean up the site of un-merchantable timber that was not worth harvesting and too difficult to replant through.

You will therefore probably need −

- Forest crop cover although optional is often good business practice

- Public liability insurance which pays for damage to other people’s property caused by a fire on your place

- Fire suppression cover which pays for the cost of putting a fire out caused by you or originating in your forest.

We suggest you get several quotes on fire insurance from different companies, or through a broker, as prices vary. Forest owners may also join together via an NZFFA branch, or informal grouping, and approach insurers to collectively insure members’ forests.

Electricity, forests and vegetation

Controlling vegetation around power wires will reduce electrical fires from this source. Vegetation falling across, or growing into, a live wire can result in fire. Wires may also sag into vegetation under heavy electrical load and may also clash together producing molten aluminium resulting in fire.

| Voltage of conductors kV is thousands of volts |

Distance in any direction from any point on conductor |

|---|---|

| 66 kV or greater | 4 metres |

| 50 kV to 66 kV | 3 metres |

| 33 kV | 2.5 metres |

| 11 kV | 1.6 metres |

| 400 and 230 volts | 0.5 metres |

Distances that vegetation should be removed from power wires for various voltages is shown in the table.

Main points

The maintenance of transmission and distribution lines is the responsibility of the line owner and land owners cannot refuse line owners access to these lines for maintenance purposes. However, where no other contractual agreement exists, the maintenance of access tracks and land under transmission lines is the responsibility of the line owner. The arrangements for maintaining the corridor through which electricity lines pass can be complicated and not all lines companies and land owners have the same arrangements.

Vegetation, including treetops and branches, must be cut back from live wires to at least the distances specified in the table. Beware of any trees outside these growth limit zones being able to fall on the live wires during stronger winds. Beware of lighting a fire beneath power wires as the electricity can arc to earth through flame and carbon particles. This is extremely dangerous if you are standing nearby as you could be electrocuted.

Common law duties relating to nuisance and negligence require that one person’s property does not have an injurious effect on another’s property. For example, trees that physically touch transmission lines can be seen as land owner’s property interfering with line owner’s property. The converse applies when the wires sag under heavy electrical loads.

Ensure vegetation is well back from power wires to minimise fire risks. Be very careful working around electricity – if in doubt get a suitably qualified person to do so. Consult the line owner about vegetation removal. Know which power lines you own and which the lines company owns and keep yours in good condition. Keep birds and vermin from nesting in meter boxes.

If you own power wires with very long spans supplying a pump house or woolshed for example, ensure that the wires cannot clash together by having closer power poles. Alternatively get an electrician to fit insulating material between the wires. Remember that power wires can sag more when under a heavy electrical load.

Gary Lockyer is from the NZ Rural Fire Authority

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand