Economies of scale in forestry

Hamish Levack, New Zealand Tree Grower May 2015.

Up to a certain point enterprises obtain cost advantages because of the scale of the operation. The cost per unit of output decreases with the rate that they are produced because the fixed costs are spread out. In addition, operational efficiency usually becomes greater with increasing scale, which reduces unit costs further. In forestry operations owners can gain economies of scale. Examples include land preparation, sampling for inventory, planning and consents, roading, harvesting, safety, freight and marketing.

Pre-harvest inventory

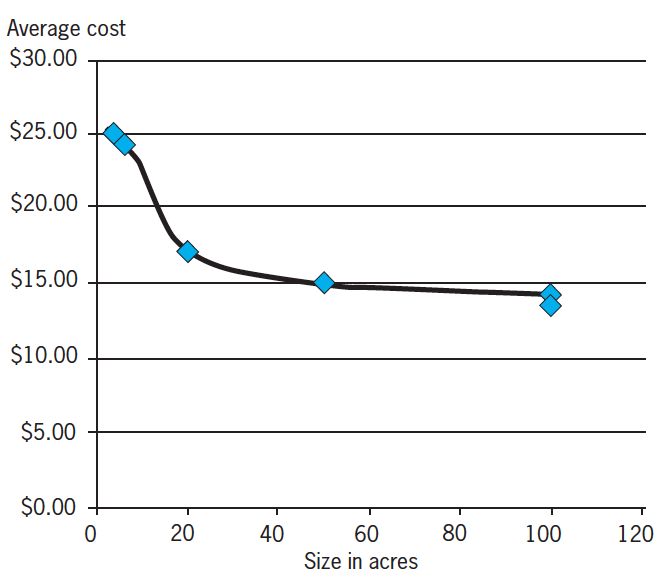

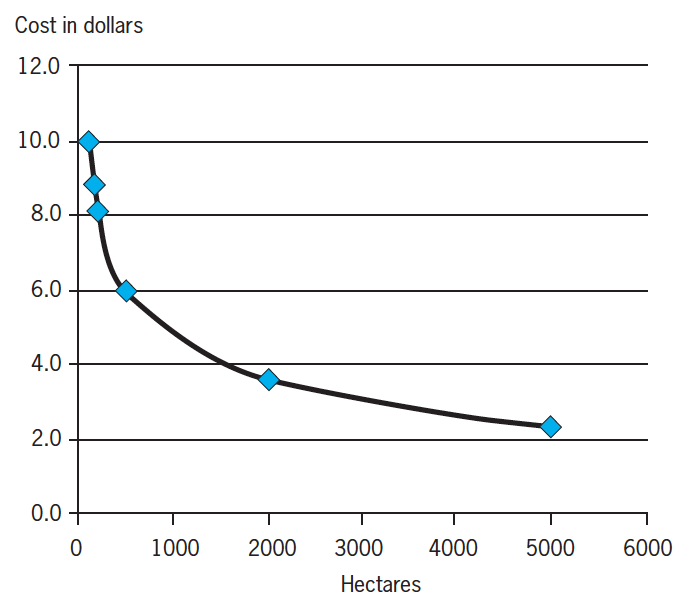

A pre-harvest inventory is used to work out the volume, quality and value of the logs in a forest. It usually involves sampling trees to provide an estimate of the recoverable volume per hectare by log grade, usually to within a 10 per cent margin of error. In its Guide to the Field Measurement Approach the Ministry for Primary Industries has published a table of the minimum number of sample plots necessary to reach that 10 per cent margin of error for carbon sequestered under the Emissions Trading Scheme.

Full inventory plots cost about $300 a plot, and this has been multiplied by the minimum plot numbers to show how inventory costs in dollars per hectare reduce with size of the forest. This is in the formula which relates the number of samples needed to determine the margin of error, and is a special case for scale economies. It is nothing to do with the spreading of fixed costs, which will provide added benefits with every extra plot surveyed.

Planning and consents

Harvesting a woodlot and getting the logs to market is a complex process. Logging, earthworks, slash management, stream crossings, mechanical land preparation, burning, replanting, tending, fertiliser application, agrichemical use, fuel management, waste management and indigenous forest protection generate environmental and social problems. They include erosion and sediment control, maintenance of soil quality, water quality, aquatic life, native terrestrial life, native vegetation, historical values, landscape values, recreation values and cultural values. Neighbours and other stakeholders need to be consulted and satisfied.

Generally, local authorities will require a plan to show the intention to avoid, remedy or mitigate adverse effects and comply with their requirements. Once the plan is accepted payment will be needed to obtain initial consents, probably from both the District and Regional Councils, and further payments will be required for their audits. Depending on the complexity of the situation all this is likely to cost something between $3,000 and $20,000. However, the economies of scale apply. A forest owner with ten times as much forest area as another will have much lower planning costs per hectare, perhaps as low as 10 per cent.

Roading

Building new roads cost about $15,000 per kilometre on flat pumice country in the Bay of Plenty. However, on unstable steep East Coast land the cost can be perhaps $100,000 or more for each kilometre of road suitable for loaded logging trucks.

If at least some of the expenditure can be shared by ensuring that the roads, or part of them service more than one forest, then major economies can be made. As well as road construction and maintenance, forest owners may face significant traffic control costs which again can often also be shared.

Harvesting

Ball-park figures for getting a hauler or a skidder in place might be $4,000 and $1,500 respectively. More importantly, the fixed costs of a logging gang’s machinery will range from around $1 million on tractor country to perhaps $2.5 million on cable logging country, although gangs equipped with brand new machinery are likely to have spent twice as much.

The table below shows why loggers are reluctant to tender for harvesting small woodlots. If they do tender, they have to increase their rates to allow for their equipment being idle while the next contract is put in place. Conversely, a contract to harvest a larger forest is much more attractive because it ensures continuity of work. As a rule of thumb, harvesting 100 hectares might keep a gang busy for a year.

| Cost of machinery | Interest at 10 % a year | Depreciation at 15 % a year | Total cost each year | Total cost each month | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Using a tractor | $1,000,000 | $100,000 | $150,000 | $250,000 | $20,833 |

| Cable logging | $2,500,000 | $250,000 | $375,000 | $625,000 | $52,083 |

It is difficult to obtain valid data to quantify the costs of harvesting overall because of commercial sensitivity and the fact that no two blocks are the same. Other factors which affect productivity are the terrain, the management regime, the average tree size, work gang composition, skill and available machinery. Nevertheless everyone who is involved in harvesting agrees that bigger jobs and the certainty of continuing work for the contractor mean significantly lower harvesting costs for the forest owner.

Harvesting example

As an example, my family bought land at Ngahape in the Wairarapa after the first rotation had been harvested. However, because of difficulty of access from our side of the Kaiwhata stream, 1.7 hectares of pines were not harvested at the time of acquisition.

Later our neighbour, Juken, who own 54,000 hectares of forest and therefore enjoy scale economies, offered to log the 1.7 hectares using a hauler operating from their side of the stream. This became part of an efficient corporate operation and the contractor charged only $30 a cubic metre.

In contrast my family had another hauler logging operation going on the same time in a 40 hectare forest block on the Kapiti coast. In this case the contractor, who did not know where or when his machinery would be used next, was charging $45 a cubic metre. This was still cheaper than the rates offered by other contracors who had tendered for the job.

Safety

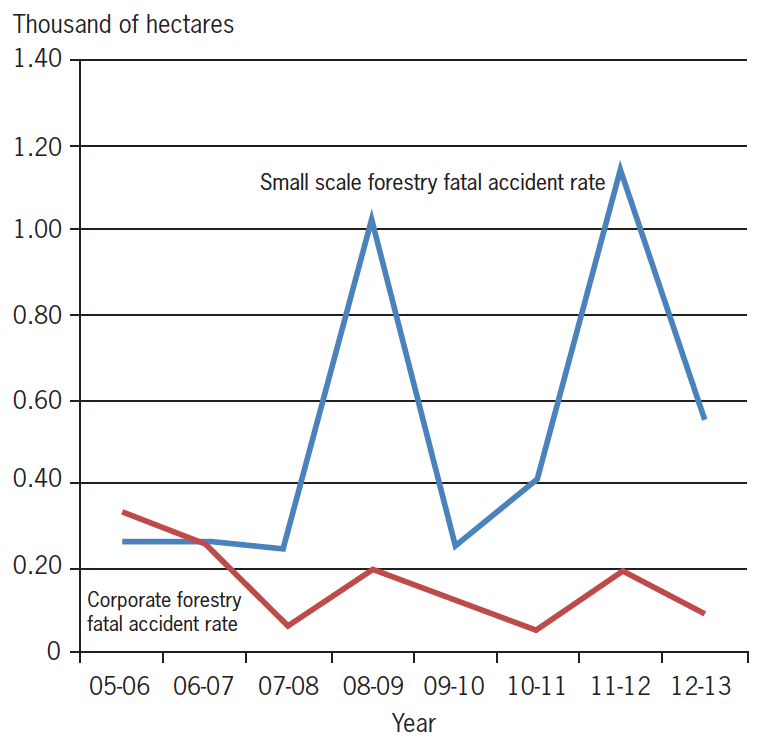

In its 2014 submission to the Independent Forest Safety Review panel the NZFFA pointed out that small-scale forest owners had more fatal harvesting accidents per hectare on their properties than corporate forest owners.

The implication is that the continuity of work provided by larger scale operations has enabled contractors to invest in more productive and safer machinery and better employee training, which has reduced accident rates. Small-scale forest owners need to be particularly concerned because, under the Health and Safety reform Bill due to become law in 2015, they are defined as ‘persons conducting a business or undertaking’. Owners will be held directly liable for any unsafe work place practices in their forests and could be fined a significant amount.

| Gang | Machinery | Scale of operation | Location | Cost per cubic metre of logging |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tippa logging managed by NZFW | Hauler | A one-off harvest involving 40 hectares | Maungakotukutuku, Kapiti | $45 |

| Juken | Hauler | Part of a regular cut of 1500 hectares a year | Ngahape, Wairarapa | $30 |

Trucking, wharfage and shipping

Trucking contractors are similar to logging contractors. They may have hundreds of thousands of dollars tied up in their vehicles, which means the trucks can cost them thousands of dollars a month even when they are not being used. As a result, better rates will be offered if continuity of work is assured. Large-scale forest owners are also better able to schedule trucking which is important because congested skids can halt harvesting, and logs left too long on the skids will be degraded by sapstain.

Marshalling and stevedoring of logs is likely to cost less if an organisation can guarantee perhaps 500,000 cubic metres throughput instead of 200,000 cubic metres. This could amount to a saving of about a dollar a cubic metre.

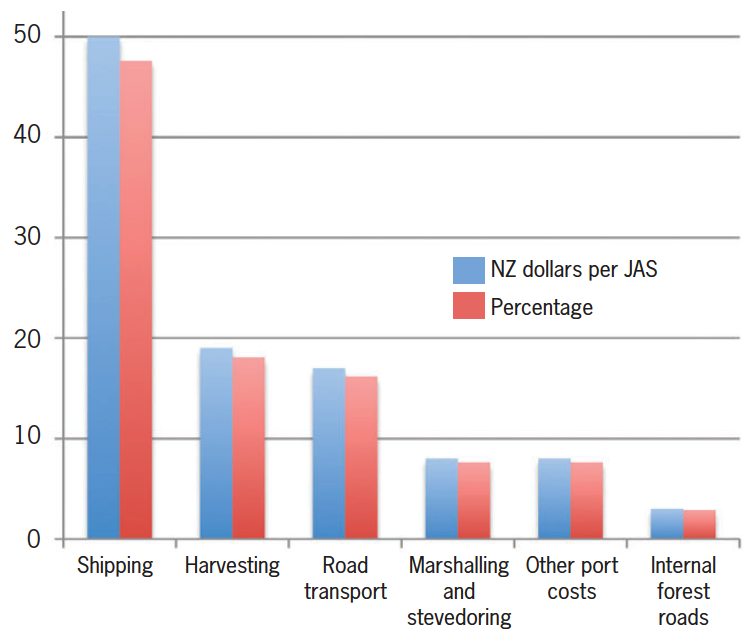

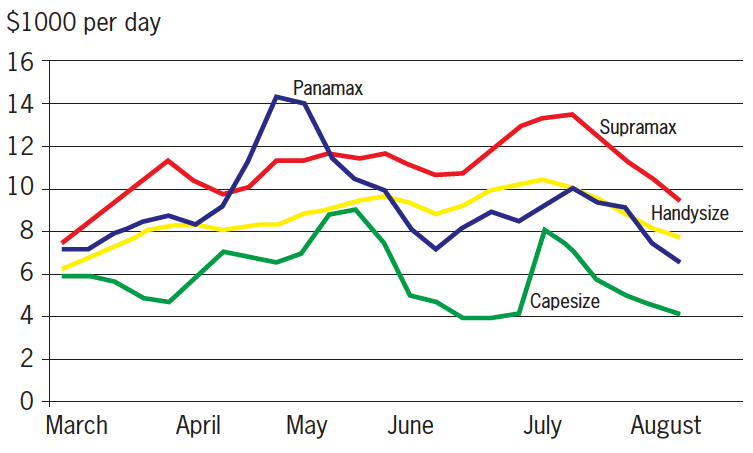

Shipping in 2012 was nearly half the cost of getting logs from the forest to China. This proportion varies greatly and at the time of writing, mainly because of a recent halving of bunker fuel price, shipping only accounts for around 25 per cent of the cost. Conversely the cost of ships transporting the logs vessels can vary significantly over relatively short periods. For example, as shown in the graph below, the cost of Panamax ships nearly doubled from about $7,000 a day to $14,000 a day between March and May 2012

Shipping

By far the greatest efficiency, and the biggest economies of scale, can be made in shipping. A ship calling at a New Zealand port usually pays the port authority about $55,000. If the charterer has enough to fill that log ship with logs in two port-calls instead of three, it could save about $1.50 a cubic metre. If the charterer has a customer in China large enough to take a full ship load of logs, meaning only one instead of perhaps two ports of call, similar savings can be made at that end.

A charterer can take out a contract of affreightment with the ship owner. This is a contract whereby the ship owner agrees to carry a specific volume of logs at a specific price for a specific time. Major savings can be made if the charterer is big enough to be able to control enough wood supply, and accurately anticipate an upswing in shipping rates. This provides a large forest owner with the ability to hedge against cost increases. For example, if a forest owner took out a contract of affreightment and then shipping costs doubled, the owner might save a loss of perhaps around $25 a cubic metre. Hedging against adverse foreign exchange movements while vessels are on the water is another way a forestry company with adequate resources can do well.

When a vessel is unable to load or discharge cargo within the contracted time, the charterer has to pay demurrage. For example, recently a vessel paid $110,000 demurrage, costing about three dollars a cubic metre, because it had to queue for two weeks outside a congested Chinese port. An organisation with flexibility of scale can often avoid demurrage by better scheduling, or even changing the intended destination port while its logs are on route to China.

Markets

Timber processors want certainty of log supply. This is a particular problem in the southern North Island where so much of the timber coming on stream is owned by small-scale forest owners. However Kiwi Lumber (Masterton) Ltd, for example, has indicated that it would be more than happy to run extra shifts, and pay a premium over and above equivalent log export prices if log supplies of sufficient volumes and grades could be guaranteed by a collective of small-scale owners. Large Chinese trading companies with their trusted long term stable customers in Asia, also prefer to deal with large rather than small-scale log suppliers from New Zealand.

Conclusion

If New Zealand’s small-scale forest owners are going to achieve their full potential profit they need to organise themselves to capitalise on economies of scale, squeezing inefficiencies out of every link in the commodity chain. The various ways that such aggregation can be achieved is subject for another article but it is very desirable that the logistics of shipping and off-shore marketing be integrated into the package.

Hamish Levack is an owner of forests in the lower North Island.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand