Forests, farms and fire

Michelle Harnett, New Zealand Tree Grower May 2015.

The most severe fire season for a decade is a reminder of just how vulnerable forests and farms can be to fire. Awareness, prevention and preparedness, with a little bit of science, go a long way to reduce wildfire risks and hazards.

You do not have to be a climate scientist to work out the summer was long, hot and dry. Shivers must have run down the spines of farmers, foresters and many others as images of property and livelihoods going up in flames dominated the evening news. Grant Pearce is a senior fire scientist with Scion’s Rural Fire Research Group, which works towards understanding fire behaviour in New Zealand’s rural and forest landscapes. He noted that last time such hot, dry conditions occurred was the 2003/04 fire season, which saw a number of significant wildfires in places like Canterbury.

On average, 3,000 wildfires are reported every year and around 6,000 hectares of land are affected, an area the size of greater Auckland. In bad years, the numbers rise, with more than 5,000 wildfires reported in 2007/2008 burning more than 9,000 hectares of land.

The areas at greatest risk are Northland and the drier regions of the east coasts of both islands – Marlborough, Canterbury, central Otago, Hawke’s Bay and the East Coast of the North Island. Nationwide, grasslands account for about half of the total land burned, scrubland 40 per cent and forest just eight per cent. The low average figure for forests masks a grimmer reality in some areas. The area of forest burnt in Nelson/Marlborough and the eastern North Island has accounted for 22 per cent and 20 per cent of the total forest areas burned since the late 1980s. Every year, a forest area greater than 100 hectares has burned somewhere in the country.

Worryingly, the area of forest burning each year is going up. It has doubled since recent records began, from about 300 hectares a year since 1988 to over 600 hectares a year now. While some of this area is native forest, the majority is exotic plantation.

Preparedness and prevention

It is not possible to change the terrain or control the weather, but land owners can take steps that reduce the probability of wildfires occurring. The New Zealand Fire Service and the National Rural Fire Authority have several publications specifically for farms, forests and home owners − Small forest management; Farm fire safe and Fire smart. All are available on the website www.wrfa.org.nz The recommendations are practical, including being aware of the fire conditions, minimising and reducing ignition and fuel sources.

Country-wide fire danger conditions are updated daily on the National Rural Fire Authority web site fireweather.nrfa.org.nz. Taking into account factors such as rainfall, temperature, humidity, wind speed and fuel type, the fire weather index ratings show the dryness of different fuel layers, along with potential speed and intensity of a spreading fire around the country.

Fire fuel sources can be controlled to a large extent by removing and keeping flammable material well away from houses and sheds, and keeping nearby paddocks well-grazed. Removing prunings and weeds from forests, clearing skid sites, keeping fence lines clear and maintaining roadsides are also measures which will help prevent wildfires starting and spreading.

People start fires

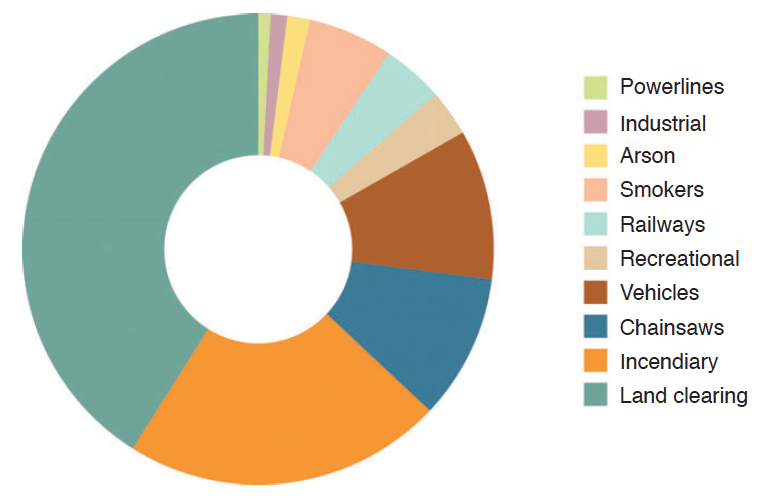

Virtually all of the wildfires in New Zealand are started by people, whether accidentally or deliberately. The causes of around half the wildfires are classified as unknown or miscellaneous, although this is decreasing with improved fire cause investigations. Considering forest fires with known causes, around 40 per cent of the total area affected is accounted for by neighbouring land clearing burns getting out of control, a further 20 per cent is due to incendiaries such as fireworks or guns, with 10 per cent each to chainsaws and vehicles. Natural causes such as lightning account for less than one per cent.

Knowing the main causes of forest fire, the likelihood of a fire starting can be reduced. As a bonus, any measures taken are also likely to go a long way towards reducing the risk of fires from miscellaneous and unknown causes.

Fire is a legitimate land management tool, but also a major cause of wildfires. Even with the right permits and the right conditions it pays to double-check with the Rural Fire Authority before lighting. It is also essential to supervise fires until they are completely out as smouldering fires can flare up days or even weeks later, especially when heavy fuels are involved.

A land owner near Blenheim found this out the hard way when a pit used to burn willow in October 2014 flared in strong south-easterly winds the following February. Richard MacNamara, Principal Rural Fire Officer for the Marlborough Kaikoura Rural Fire Authority, told the Marlborough Express that the heat had remained in the heavy fuels, burning very slowly.

Farm and forestry activities involving chainsaws, mowers and any other machinery and vehicles that could become hot or cause sparking are also mainly under a landowner’s control. Common sense measures, such as keeping equipment clean and in good condition with spark arrestors fitted as necessary can go a long way to reducing the risk of fire. If the fire risk is extreme, consider postponing work.

In general, landowners, managers and operators are very aware of the risks and hazards around using fire. Other groups which use fire can be classified as recreational or cultural users and there is the vast majority of the population who do not use fire at all.

A group which causes concern are the recreational fire users, who are usually local or international visitors, or absentee landowners.They are the ones who light camp fires and set off fireworks.They are unlikely to be aware of the local fire risk, to take any preventive steps or to be prepared to respond if a fire starts.

Talk about fire safety

Land owners can take several approaches to deal with human factors outside their control. One is to talk about fire safety with people who visit and use forests for recreation, and with contractors working on the land. With contractors in particular, make sure their contract specifies conditions for the safety of others, themselves and the forest, and that they have liability insurance and fire suppression cover.

The other main approach is to keep fire starters out by discouraging trespassing and illegal activities. While there is not much information on arson and the negligent use of fire, it is likely that many of the fires with causes classified as unknown or miscellaneous are started by people who should not be there. Some suggestions for restricting access include locking gates, using barriers like drains, and blocking potential entry points.

Predicting fire behaviour

Despite best intentions, fires start. Grant Pearce was at the Flock Hill fire which scorched its way across 330 hectares of Canterbury near Arthur’s Pass in late January. He said that dry and windy conditions spread the fire through dry grass and shrub into difficult terrain with wilding pines and beech forest. Once into heavy fuels it developed into a high intensity crown fire that was almost impossible to control, even with the large number of helicopters and fixed-wing water bombers. Burning embers were being transported half a kilometre ahead of the main fire, starting new fires and causing erratic fire spread.

The speed of the Flock Hill fire and its intensity were frightening, but the behaviour of fire is mainly governed by known factors and can be predicted for all but the most extreme conflagrations. Scion’s Fire Research group has been working on modelling fire behaviour and developing systems which fire-fighters can use in the field. The result is Prometheus, named after the mythical Greek Titan who brought fire to man.

Fire resistant plantings

Fuel is the only component of a fire environment which can be altered to reduce the probability of extreme wildfires occurring. Species that do not burn easily can be planted as buffers around homesteads and forest blocks. Trees and shrubs with high moisture and salt contents, low volatile oil contents, smooth bark and broad fleshy leaves tend to be most fire resistant.

Natives such as Griselinia species, Coprosma species, Pseudopanax species, ngaio, koromiko, mahoe, lemonwood and tree fuschia fit the bill. A 10 to 20 metre wide planting will offer some protection. They will eventually burn, but not easily. Planting buffer species will also increase biodiversity and provide food and habitats for native birds and animals. At the other end of the spectrum, manuka and kanuka catch alight easily and burn intensely.

Prometheus is a Canadian wildfire growth simulation model adapted to New Zealand conditions. Using information such as the fire weather index, fuel types and fire behaviour models, and the local weather and terrain, it predicts fire behaviour and spread across the landscape as conditions change. Using data from Prometheus, fire managers can develop a suppression strategy which considers if the public need to be evacuated and fire fighter the location and safety of fire crews.

Using Prometheus

Prometheus was put to good use in February to fight the 600 hectare scrub and forest fire at Onamalutu in Marlborough. Fire Scientist Veronica Clifford, who is also a rural volunteer firefighter, worked alongside the incident team managing the fire. Using up-to-date weather forecasts for the area and looking at the fire’s fuel types, she was able to simulate what the fire was likely to do over the next 12 hours. She then passed this information to the fire management and the fire crews at the twice daily shift changes.

Principal Rural Fire Officer Mac McNamara said that having a fire scientist on the team meant fire crews received real time advice on a complex fire, with multiple fuel types on rough terrain. He said that they used Veronica’s predictions to make decisions on where to concentrate firefighters and aerial support, and when evacuation might be necessary.

The wind changing direction was especially concerning. When they knew a southerly change was on its way, they tracked its progress closely. The fire crews were working among tall timber at the time and there was the risk of fire-weakened trees toppling when the wind changed. They predicted the change would arrive at 5.00 pm. It arrived at 5.02 pm and the fire crews were clear and safe.

The Prometheus software can also be used for planning before fires occur to assess the potential risk of fire spread in ‘what if’ scenarios. After the fire it can determine how effective fire suppression operations were and to value the properties, infrastructure end even lives saved.

Scion’s rural fire research team has worked with MBIE, the New Zealand Fire Service Commission and the New Zealand rural fire sector to develop and refine Prometheus. A fire behaviour calculator has also been developed. Apple and Android smartphone versions of this can be downloaded. Farmers and landowners can use the app to predict fire behaviour more accurately and reduce the risks associated with potential escapes from burn-offs.

Reduction, readiness and response

The Flock Hill and Onamalutu fires were large and spread rapidly, covering more than 1,000 hectares between them. Such large wildfires are likely to occur frequently in future as the weather changes, predicted to accompany climate change with higher temperatures, increased wind speeds and decreased rainfall, increase the severity of fire seasons. Everyone should have a plan for dealing with fire, starting with being aware of the risks, reducing hazards and causes and being ready to respond if necessary.

With autumn rain reducing the wildfire risk in most parts of the country, now is a good time of year to take stock, clear away potential fuel sources and hazards, and plan and prepare for a fire-safe summer on your rural property.

Michelle Harnett is a science communicator at Scion. Scion’s Rural Fire Research Group is based in Christchurch and carries out research on fire in New Zealand’s rural and forest landscapes.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand