Harvesting a forest of 22 to 23-year-old trees

Graham Milligan, New Zealand Tree Grower May 2019.

Like all keen farm foresters, we have planted our share of trees over the years. This has included several blocks of forestry species dominated by radiata pine. Having harvested a plantation over 20 years ago in two hits

I was no stranger to the satisfaction of seeing the log trucks heading down the road and receiving a good return as a result. Those trees were established by my father in 1967 and were pruned and thinned by, at the time, textbook standard.

Four years ago we harvested another block which was 30 years old. This was established on river country, dominated by gravels and a fluctuating water table governed by river levels. Early on we were plagued by tree deaths due to root rot and we were halfway though the low prune when a severe gale blew many over. Any further silviculture was discontinued.

Half of the radiata pine were interplanted with Eucalyptus nitens and although this appeared to protect the pine from windthrow, the health and vigour of the E. nitens ensured the radiata struggled to compete. When we logged the area, taking out the radiata only, returns were about three times what I expected. Due to the mixture of species it was hard to determine the actual area in conventional terms, but I would estimate it was three hectares.

Taking the plunge

In the early 1990s I could see the returns from livestock on most of our hill country was not at all comparative with the much larger returns from forestry at the time. We took the plunge and planted four blocks during the 1990s, comprising mostly radiata pine but also some Douglas-fir, macrocarpa and a small area of Leyland cypress ferndown.

The block we recently harvested was 20 hectares of radiata planted in 1995 and 1996. These were two of coldest winters on record and many trees in one area planted in 1995 were frosted and several hundred were killed. We blanked these by planting replacement seedlings in June 1996. But these were also killed by frost in the major freeze of 1996.

I had grown a number of radiata seedlings in small side-slit trays for planting in 1996 and we used these. The the contract planters who struggled to plant on the worst of the rocks found these little plugs easy to slip in to a very small hole and I am sure every one of these trees grew. All trees planted were 18-month-old topped GF17 radiata. The only exception was a year 2000 planting where we grew several thousand trees in small plugs from seed collected from nearby wildings of superb form.

Planting more, not pruning

I worked out some figures in the late 1990s which convinced me that if you have a land bank suitable for forestry, on what was at the time a limited budget, planting more trees rather than pruning what we already had was much more profitable, so we carried on planting. With our family returning to work in the business and an ever-increasing work load we never got to thin the first three blocks, but we thinned the last block which was planted in 2000.

Why did we harvest a block of 22 to 23-year-old radiata pine? The reasons were many. In November 2015 there was a major fire within 1.5 kilometres of our nearest forestry. It took nine helicopters over four days to extinguish but not before it burned around 30 hectares of young radiata pine on a near neighbour’s property. Everyone was impressed at the efficiency of the helicopters flying at times in very strong winds, but the cost of firefighting alone was over $500,000. Although it is not public knowledge what insurance was paid out to the owner of the trees, there was much acrimony between all parties concerned.

On the day the fire was contained the forecast was for severe gale force winds, and the Rural Fire Authority who oversaw the operations had projections that not only would involve house evacuations, but would have probably burned all our forestry as well as potentially many hundreds of hectares of nearby plantations. Although gale force winds were experienced in the Waiau Valley in western Southland, we missed completely, but there were many nervous moments.

| Grade | Log lengths in metres | Volume in tonnes |

|---|---|---|

| A | 3.0 | 454.78 |

| CHIP | R | 1297.40 |

| FIRE | M | 20.54 |

| K | 3.0 | 14.52 |

| K | 3.6 | 12.36 |

| K | 3.8 | 2535.10 |

| KI | 3.0 | 166.88 |

| KI | 3.8 | 60.44 |

| KIS | 3.0 | 363.42 |

| KIS | 3.8 | 63.10 |

| KX | 3.8 | 3843.72 |

| L30 | M | 2630.46 |

| L30 | S | 1493.48 |

| POLE | 42.20 | |

| POST | M | 308.14 |

| TOTAL | 13306.54 |

| Log grade | Customer | Description | Cut length in metres | Max knot size cm | Minimum small end diameter cm | Sweep | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L30M | Niagara | Domestic | Longer length medium/large diameter unpruned sawlog, produces predominantly cutting grade along with industrial grade. | 4.3 − 4.6 − 4.9 − 5.2 5.5 − 5.8 − 6.1 | 15 | 30 | 1/4 |

| L30S | Niagara | Domestic | Shorter length medium/large diameter unpruned sawlog, produces predominantly cuttings grade along with industrial grade. | 3.7 − 4.0 − 4.3 | 15 | 30 | 1/4 |

| Poles | Stuarts | Domestic | Very straight small to medium sawlogs with small branching | 3.7 − 4.3 − 4.9 − 5.5 − 6.1 | 4 | Min 16 Max 24 | Straight |

| Posts | Stuarts | Domestic | Straight small sawlogs with minimal taper and small knot | Random, preferably 3.7 − 5.5 − 7.3 | 4 | Min 10 Max 22 | 1/8 |

| A | Rayonier | Export | Short length medium/large diameter unpruned sawlog | 3.12 | 12 | 30 | 1/4 |

| K | Rayonier/PF Olsen | Export | Short & medium length medium diameter unpruned sawlog | 3.12 − 3.72 − 3.92 | 10 | 22 | 1/4 |

| KI | Rayonier | Export | Short & medium length medium/large diameter unpruned sawlog with larger branching & more sweep tolerance. | 3.12 − 3.92 | 20 | 26 | 1/3 |

| KX/KIS | Rayonier/PF Olsen | Export | Small to large sawlog of poorer form and larger branching. | 3.12 − 3.92 | NL | 10 | 1/2 |

| Chip | Dongwha | Domestic | Small to large diameter poor form, bent logs and large branching. | 3 to 6 | NL | Min 10 Max 65cm |

1/1 |

A forest full of straight trees

Because of a guilt syndrome caused by never getting around to thinning, I had not been for a walk among the trees for a year or two, but in October 2017 I took the time to walk through a good cross-section of the 20 hectares. I was expecting to see a mass of post-size material because we had planted at 1,500 stems a hectare. What I saw was a forest full of tall straight trees with a large number of reasonable diameter trees.

Having been involved in forestry for over 50 years I have read many articles and listened to many presentations on how to maximise profitably of the radiata pine crop. This is by using the latest genetics and managing the pruning and thinning to achieve a maximum number of logs into the highest paying grades at point of harvest which is traditionally at 30 years of age. What happens in reality is that for the private forester the greatest profit is made by choosing to sell at a high point in the market, always a guess of course, but prices looked good to me.

Sell when you need money

A wise friend and fellow forester and neighbour told me many years ago that the best time to sell your trees is when you need the money. His axiom has stuck with me for many years when our debt loading was such that there appeared to be no end to the debt tunnel. However, we have lived long enough to have paid off all debt so in the end it was not a factor, but with four forestry blocks at or a very close in age class, it did not make complete sense to have the tax implications all loaded over five or so years.

With all this in mind it seemed a good idea to get a price from a log buyer to see what we could expect from the 20 hectares. The most important factor when choosing a log buyer is trust. I have known Greg for many years and his respect in the industry is impeccable and that includes the logging gangs he employs. I went against my own advice by not getting quotes from other log buyers in the industry.

All about the money

Greg organised a number of plots and I told him that I wanted a stumpage quote. This is a price per ton for the whole crop rather than an estimate of volumes of various grades of logs and a price for each grade. Both methods have their advantages, but in this case but I preferred the stumpage method because of the smallness of the material. Greg and I agreed that if the block was left for another few years the volume would not change a great deal and the mix of grades would be very similar.

The price I was offered was $43.27 a tonne of wood. Remember, this is the same price for chip as it is for the L30 grades and everything in between. The volume was estimated at 560 to 610 tonnes a hectare or up to 12,020 tonnes for the 20 hectares. At a gross return to me of up to $520,000 it was a very attractive proposition, but what would it cost for a road? There was a track to the top of the block that had to be improved and the approach on to the public road need a lot of earth moved.

We got a quote for the road from a company who I have had a lot of dealings with and he rung me to quote $50,000 to $60,000. When I asked whether he would send a written quote, he said he could write it on the back of an envelope if I wanted. We had rock and gravel on the site, so the approval was given and we made the decision to go ahead with the harvest. The length of the road was 1.2 km and in early March the roading contractor moved in and started. We ended up with a good road requiring occasional maintenance. Between 400 and 500 truck and trailer movements are a sure test for a newly formed road especially after heavy rain and during the winter.

What we did not expect were the continual accounts arriving from the roading contractors amounting to $100,000 which was $40,000 above the high estimate.

Once logging began in early June for an estimated 12 weeks, although it was nearer 14 weeks due to the volume being over the estimate, things went smoothly.

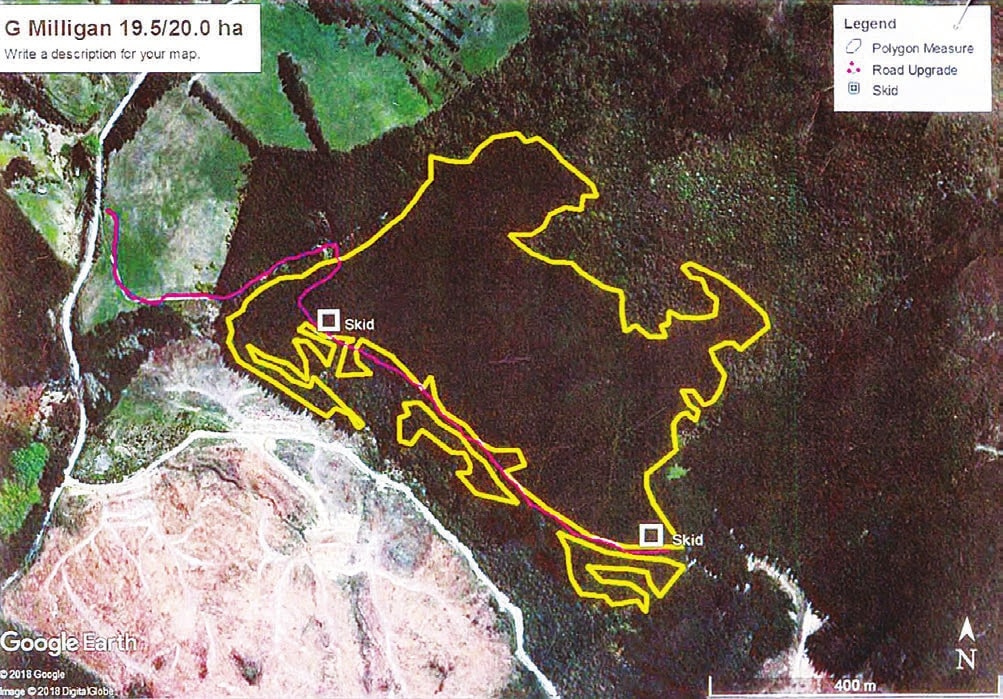

The logging was carried out with two digger/skidder/ static de-limbers and the logging crew were great to deal with. There were two skid sites – one at the top and one near the bottom of the block as shown on the map.

How did we fare?

The block produced 13,100 tonnes – 1,080 tonnes over the higher estimate, and a gross return of $575,770. We paid $2,592 in log levies for a nett return of $573,181.

You could argue that the extra $53,000 over estimate more than covered the blowout in roading, but it would have been good to have had it in the back pocket. Obviously, apart from tax implications, there will be a cost in wind rowing and planting which is earmarked for next winter.

Before planting the trees, the 20 hectares had been used as part of the grazing operation in the sheep and cattle part of the business. The question as always with farmers is what we lost in the livestock operation. The answer is always hard to quantify.

My guess is the area probably carried three stock units a hectare and the annual gross return probably in the vicinity of $400 a year on today’s buoyant prices, but more like $200 in the bad years. Allowing a relatively tawdry $150 for running expenses, my estimate is a generous $150 a hectare each year we lost in grazing income or $3,450 per hectare for the life of the forest − $20,000 for the forestry after tree establishment and roading.

We are in the initial stages of family succession for our operations and one of the discussions is if we should we plant all our property in trees. It may not happen due to factors such as fire risk and disease potential, but as the figures show, profitability from forestry, particularly on land less suitable for pastoral livestock farming, will win hands down and once regular harvests can be achieved from our forestry estate, cash flow is a much more attractive option than the daily grind which is livestock farming.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand