Continuous cover forestry - an introduction

Ian Barton, New Zealand Tree Grower November 2005.

This article covers the basic principles of continuous cover forestry. The second part, due to be published in the February Tree Grower, will deal with establishment, silviculture and harvesting.

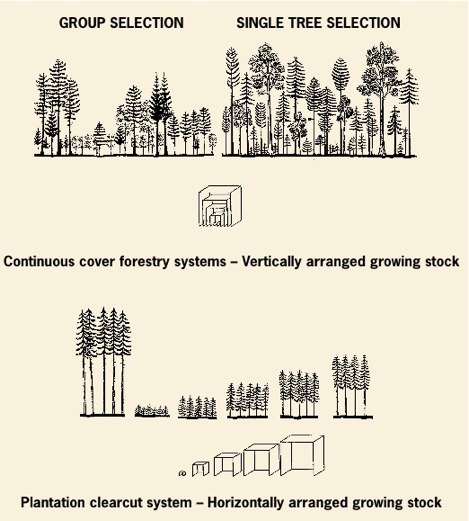

Continuous cover forestry is usually defined as the use of silvicultural systems which maintain the forest canopy at one or more levels without clear felling. The requirement is the management of forests using ecological principles which mimic natural processes, to maintain the forest canopy at one or more levels, and to ensure that the forest will, as far as possible, be self regenerating. Because harvest removals are by single tree or small coupe fellings, other forest values are maintained and often enhanced. Continuous cover forestry is a sustainable system.

Management activities like releasing, pruning, thinning, harvesting and regeneration are carried out continually or irregularly through the whole of the forest area. There is no clear felling of trees when they reach some pre-determined age. During harvest the felling of areas wider than two tree heights is avoided which means that felling coupes seldom exceed a quarter of a hectare in area.

There are many alternative names for continuous cover forestry – dauerwald, ecological forestry, selective cutting, close to nature, near natural forestry and holistic forestry. Basic to all of these terms is the concept of maintaining the forest cover in as complete a way as possible. Therefore continuous cover forestry is not a silvicultural system in itself but rather a method of management which can be based around several silvicultural systems, using the most appropriate one for each phase of management.

There are many alternative names for continuous cover forestry – dauerwald, ecological forestry, selective cutting, close to nature, near natural forestry and holistic forestry. Basic to all of these terms is the concept of maintaining the forest cover in as complete a way as possible. Therefore continuous cover forestry is not a silvicultural system in itself but rather a method of management which can be based around several silvicultural systems, using the most appropriate one for each phase of management.

One of the most important aspects of continuous cover forestry is that it can include a wide range of forest uses with minimum compromise and without needlessly affecting the health of the forest. Management of the forest for such important environmental and social factors as biodiversity, natural ecological processes, landscape protection, recreation and soil and water values are an important part of the process.

In a world becoming increasingly conscious of environmental degradation, continuous cover forestry should be regarded as a very viable option for forest management. This applies especially to growing high quality timbers. Most New Zealand native tree species are somewhat shade tolerant. Therefore, with the exception of beech, they commonly grow in mixtures of several species so our forests are well suited to management using continuous cover principles.

The principles of continuous cover forestry

There are four main principles involved in continuous cover forestry management.

Adapting the forest to the site

Working with the site and adapt the forest to the site and its inherent soil and micro climate variations, rather than imposing some form of artificial uniformity. For example a species like kauri must be suited to the site with temperatures not falling below about –4°C, reasonably well structured soil, an adequate summer water supply, moderate shade and shelter as a seedling and full light when well established.

Adopt a holistic approach

Instead of concentrating upon the growing of trees for timber the process should be to create, maintain and enhance a functioning ecosystem. Although timber production is one of the main aims, the forest should retain features of the wild forest, which will result in higher values for factors such as biodiversity, landscape protection and soil and water benefits.

Maintain forest conditions and avoid clear felling

Clear felling of areas larger than about a quarter of a hectare will modify the forest floor to an unacceptable extent unless the species being regenerated requires reasonably high light levels.

Continuous cover forestry processes must maintain the vertical structure of the forest. Beech forest may have only two or three strata but most New Zealand indigenous forests have four fairly clearly defined layers – dominant, sub-dominant, shrub and ground. Because the plants in each one are important parts of the eco-system their individual integrity is vital to the ecological integrity of the forest.

Management of the growing stock

Forest improvement is concentrated upon the development of individual trees rather than stands or compartments of trees. The objective is to select for retention rather than removal and to concentrate growth of the best quality wood on the best stems. This means that yield control is based on regeneration and increment rather than age, stand volume and area.

Historical background

One of the most important components of continuous cover forestry is sustainability, which was first developed into a silvicultural system by the German forester Gayer about 300 years ago. It was another German forester Möller, who took Gayer’s ideas in 1922 and developed them into the modern concept of continuous cover forestry. For Möller the forest was an organism, not a wood factory, which required cautious management following natural successional processes.

Unfortunately, the development of large scale plantation forestry at about the same time tended to overshadow the values and benefits of continuous cover forestry which languished as a management system until revived about 20 years ago. In Central Europe today the movement from clear felling and uniform conifer plantations to continuous cover forestry gathers momentum and has strong support from small private owners.

Pleas on deaf New Zealand ears

Early forestry initiatives in New Zealand gave consideration in the 1870s to the application of continuous cover principles to our native forests. The man proposed to be our first Conservator of Forests, Captain Inches Campbell-Walker wrote about the practice of forestry in the United Kingdom and Germany and outlined some of the forest management methods then being practised in Europe. He urged taking steps to ‘…improve our Plenter-betrieb or selection of single trees to be felled so as to gradually arrive at groups of trees of the same age, description and class and eventually at blocks worked in rotation, and containing always a sufficient stock of crop coming on to meet the requirements of future years.’

Unfortunately the New Zealander’s of the time were more interested in removing forests to make farms, and Campbell-Walker’s pleas fell on deaf ears, as did subsequent urgings to better manage New Zealand’s indigenous forests. In fact, apart from brief spasms of interest in sustainable forest management between 1920 and 1970, successive New Zealand governments have demonstrated a profound lack of knowledge and interest in this subject.

Some farsighted foresters

However some farsighted New Zealand foresters have attempted to implement sustainable management of our indigenous forest. Ensor recommended that beech forest could be managed either by a selection or uniform system. This approach was supported by others and has been brought to fruition with black beech by John Wardle, while others are beginning to succeed with the management of silver and red beech.

Work with rimu has not been as successful, although early studies suggested that selection management of these stands would be twice as productive as attempting to manage them as even-aged stands. More recently the use of helicopters for single tree extraction has enabled a sustained management approach of minimum intervention to be used.

Early kauri management studies concentrated on the extraction of mature trees. This did not lend itself to sustainable management because of the over mature, large sized trees, often dense stands and poor soils involved. More recently the emphasis has been on managing second growth stands using single tree and group selection.

Totara has only recently been studied in depth and information on its management can be found in David Bergin’s excellent book – see page 11 for more details. Regrettably there is not much information on most other New Zealand species, but what is available suggests that several others will be very amenable to management.

Hope for the future

Today the practice of continuous cover forestry in New Zealand is beginning to gather impetus. Udo Benecke has written several articles and papers about its use with indigenous forests and some farm foresters are beginning to consider the adoption of these principles. At least one district council is in the process of incorporating continuous cover forestry into its rural planning.

Ian Barton is a Registered Forestry Consultant & Chairman of Tane’s Tree Trust.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand