Pine plantations and water quality in central North Island lakes

John Quinn, New Zealand Tree Grower November 2005.

Increasing nutrient levels threaten the quality of many central North Island lakes. A long term study showed that nutrients leaking from land to water decreased markedly when a central North Island catchment was converted from pasture to pine plantation. Logging and replanting caused a short term increase in nutrient losses but these dropped to low levels as active forest growth resumed.

Lakes and land use

Many of the lakes in the central North Island are suffering from increased algal growth and reduced water clarity. These are symptoms of nutrient enrichment by phosphorus and nitrogen that are contained in the groundwater and surface run-off from the surrounding catchment and wastewater inputs.

Replacing pasture with pines reduces this nutrient export, but what happens when the pines are logged and the site replanted?

NIWA scientists have been studying this at the Purukohukohu Experimental Basin, on the Paeroa Range, near Reporoa. This was established in the 1960s as a long term research site on the effects of land use on soil processes and streams. Although the streams drain into the Waikato, they are similar to many that feed into the Rotorua lakes.

The area in pasture was cleared in the 1920s as part of Mangimingi Station. The Puruki catchment was planted in radiata pine in 1973 then logged and replanted in early 1997. Water studies have investigated the effects of land use on water flows, quality and nutrient exports downstream of pasture, pine and native forest by comparing nearby paired catchments.

Water yield

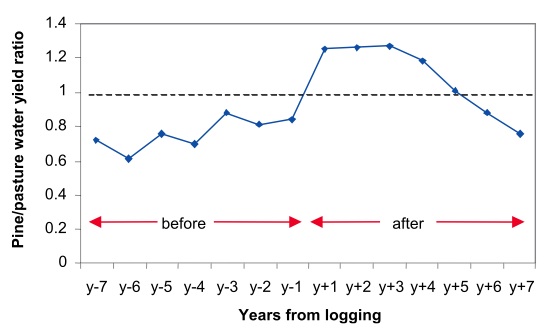

About 30% less water flowed from the mature pine plantation than the pasture as shown in the diagram. This is expected to be due to the pines increasing the interception and evapotranspiration of rain. Flows were higher from the pine than the pasture catchment for four years from logging, but returned to pre-logging level by seven years after logging.

Nutrients

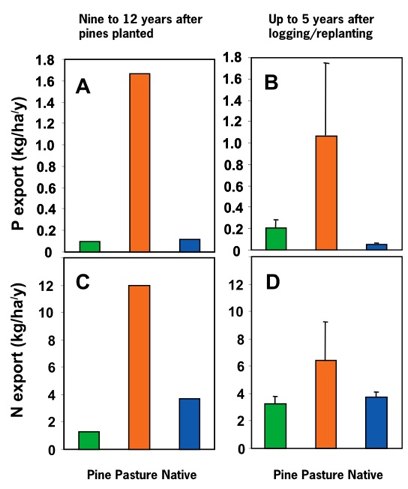

The stream draining an established pine plantation, 9 to 12 years after planting, exported less nitrogen and phosphorus than the adjacent pasture stream and less than native forest. The lower catchment export from pines compared to pasture probably results from the combined effects of –

- lower fertiliser input

- removal of grazing stock whose urine patches create local hot spots of high nitrogen loading

- reduced stream bank and soil erosion and surface run-off

- uptake and retention of nutrients by the growing pine trees and understorey vegetation

- inhibition of nitrification – transformation of ammonium-nitrogen to more readily leached nitrate – by mycorrhiza associated with actively growing tree roots.

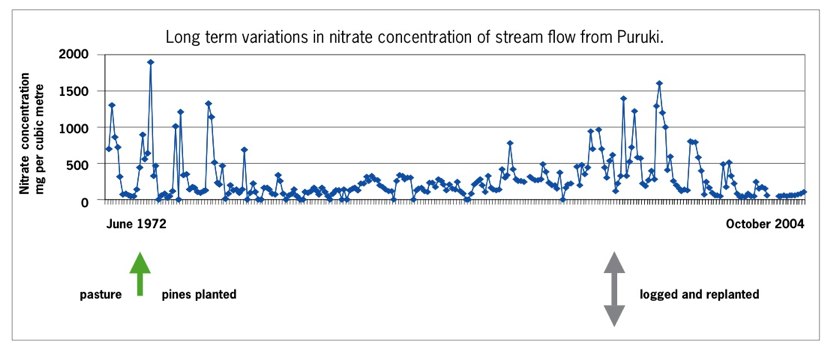

Nitrate dominates the nitrogen export from these catchments. The long-term monitoring of nitrate concentration in the pine stream shows that this declined over the four years after conversion from pasture to pine plantation. However it increased somewhat late in the pine rotation, suggesting mature forest was more ‘nitrogen leaky’.

Nitrate concentrations increased in the pine stream in the two years after the time of logging, where these were similar to levels when the land was in pasture. However, nitrate dropped from three years after logging and replanting as the groundcover and the replanted pines became established, and was very low after seven years.

Conclusions

These findings indicate that the increase in nutrient loss around logging and replanting is short-lived. Over the whole cycle of pine planting, forest growth, logging and replanting, pine plantations export less much nutrient than pasture. Pine plantations within lake catchments in the central North Island are likely to be at different rotation phases. Therefore short-term increases in nutrient yield around logging of one plantation forest patch will probably be more than compensated for by the low yield from younger pine forests elsewhere in the catchment.

The overall effect of afforestation of pasture on nutrient yields remains beneficial. The higher nitrate yields from mature forest than young forest, and lower yields a few years after logging than immediately before, also suggest that logging may be beneficial for long-term nutrient yield with a vigorous growth mode with high nutrient retention.

This research was funded by the NZ Foundation for Research Science and Technology through Scion’s Centre for Sustainable Forestry Programme Protecting the environment through forestry.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand