Everyone likes larches

Nick Ledgard, New Zealand Tree Grower November 2007.

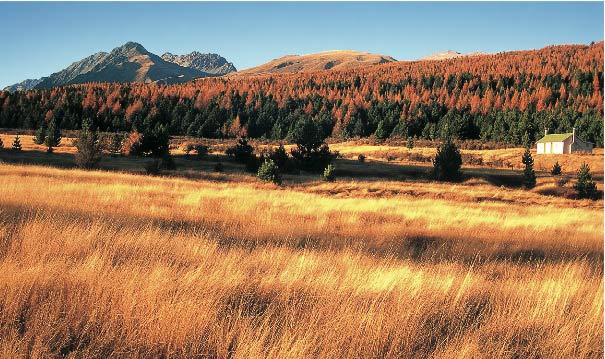

Everyone likes larches. As a tall deciduous tree with attractive autumn yellows and spring greens, it can be very eye-catching. It is a favourite of my wife’s, and in our early years together I was instructed to plant some on our North Canterbury plot of land. Being a newly-wed, I did as told, even though it was rather against my better judgment, as larch is not a species for dry and exposed lowland sites. Now, 32 years later, the signs of a struggle are very apparent... small diameters, swept stems and suppression by neighbouring pines, which are better suited to such a site.

Late frosts can be damaging

In the early 1980s, I spent two summers visiting nearly all stands of trees in the high country between Molesworth and the Lindis Pass. We often came across European larch, Larix decidua, as it likes the more continental environments and is a tough tree capable of surviving on a wide range of sites. However, trees of good growth and form were only seen on sheltered slopes in the higher rainfall areas. The slopes are needed for good air drainage, as larch flushes early, and late frosts can be very damaging for new spring growth.

There are 10 species of larches endemic to the cooler regions and mountains of the northern hemisphere. The two most often seen in New Zealand are European larch and Japanese larch L. kaempferi, with the former being more cold tolerant than the latter. European larch is widely cultivated in its European homelands, and arrived in 1850 in this country with an established reputation as an important forest and timber species. It proved easy to raise in nurseries and was planted quite widely initially.

Early height growth rates were often impressive, but this was not readily carried through to high volumes in later years compared with Douglas fir. In the late 1980s, the two larch species occurred in around 5,500 hectares of plantations, but much of that would have been felled since and not replanted with the same species.

Surges of interest

Virtually no-one is establishing plantations of larch these days. A natural hybrid between the two has also been grown on a much smaller scale, and has shown signs of extra hybrid vigour. There has also been occasional surges of interest in western larch, L. occidentalis, as it originates from western North America, from where come a number of other conifers which perform well in this country.

Although there are good specimens in the likes of the Lake Coleridge and Albury arboretums, western larch has largely been unsuccessful, as too many plants failed to survive the nursery stage.

European larch produces a moderately high density wood, 560 kg per square metre at 12% moisture, with an obvious colour difference between sapwood and the darker orange-coloured heartwood. As such, it is very similar to Douglas fir, from which the sawn timber can be difficult to distinguish. Larch generally has the more frequent, smaller knots. Japanese larch is slightly lower in density at 496 kg per square metre.

Above ground durability

The wood of both species has excellent toughness and stiffness and is well suited for many of the same structural purposes as Douglas fir. However like Douglas fir, it can be difficult to surface finish due to the abrupt transition between early wood and late wood, which results in alternating soft and hard bands in successive growth rings. This surface grain characteristic can be attractively accentuated by sand blasting.

With its high proportion of heartwood, larch arrived in this country with a good reputation for durability in the ground but unfortunately this has not proven to be the case in New Zealand. However, it has good durability above ground and is still favoured for the likes of log houses – where straight stems can be found – and trellis making.

Silviculturally, larch is treated differently from Douglas fir, as it is more space and light demanding. Therefore a final crop stocking of around 400 stems per hectare is usually recommended. In the past, it was often used in mixtures with other species, such as Douglas fir, western red cedar and grand fir. However, proper management of such mixtures is not easy, and few foresters have achieved the profitable results they were after.

Among the common conifers, larch has one of the lighter seed weights, so seed can be readily blown some distance to give rise to wilding spread. In fact, in the high country survey of the early 1980s, this species had the highest incidence and distance of spread of all the more common plantation species, contorta and Scots pine not included. Therefore, it should not be planted upwind of lightly vegetated or lightly grazed land.

Due to their attractive appearance and almost iconic presence in popular tourist towns such as Hanmer Springs and Naseby, the larches will remain an obvious component of some landscapes for many decades into the future. But they are unlikely to be planted as plantations, mainly due to their good wood properties being very similar to those of Douglas fir, which is more site tolerant, faster growing and capable of carrying higher volumes of wood per hectare.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand