The Kapiti Proposed District Plan - A tale of two halves

Don Wallace, New Zealand Tree Grower November 2015.

We own 60 hectares of rural land in the Otaki Gorge, about 70 km north of Wellington, most of which is in forestry. In late 2012 the Kapiti Coast District Council notified its Proposed District Plan which, if implemented in its original form, would have severely restricted forestry and other activities on our land. This article has two purposes −

- To describe the process rural ratepayers in Kapiti have been following in trying to get the proposed plan transformed into something that they can live with

- To provide others facing a district plan change with ideas as to what they can do to influence what happens in their district.

Early days

On 11 December 2012 the Kapiti Coast District Council sent a letter to all property owners calling for submissions on its Proposed District Plan. The two page letter contained general information on the plan and on the process for submissions. It gave the impression that no major changes were expected and we innocently believed the misleading statement placed in the middle of the letter −

For most residential areas, the Proposed District Plan is generally ‘business as usual’ with minor changes to rules such as new design controls to front fences and reduced permitted site coverage. The same is true for most rural areas, although a key proposal is to seek increased clustering of new buildings and lots.

Based on this, and that we had not been advised that there was anything special about our property, we assumed the changes proposed would have little effect on us. That was until we received a note from a public-spirited rural landowner pointing out what the plan was proposing for our properties.

The plan includes a range of new rules and provisions that may affect your property. For example, as a rural resident my property is covered by new rules relating to prominent ridgelines, outstanding landscapes, priority areas for restoration, and eco-site changes. ... I think it is important that people have the opportunity to understand the potential impact on their property and surrounds.

The note included a copy of the map covering our property and from what it showed, it looked like we would be similarly affected. This spurred us into action and we decided to do two things − alert our neighbours to what was happening and have a look at the plan to see how we were affected.

The first was quickly accomplished but the second took a little longer as the council had not printed sufficient copies of the plan and there was a significant waiting list to get hold of one. The council also made the plan available electronically. However, it was in excess of a 300 megabyte download and, given the need to cross reference between sections, a printed copy was the only practical way to proceed.

Studying the plan

| Provision | Coverage |

|---|---|

| Rural Hills Zone | 100% |

| Sensitive Natural Features | 100% |

| Moderate Erosion Susceptibility | 30% |

| Lowland Hills Eco Domain | 90% |

| Hill Country Eco Domain | 10% |

| Priority for Restoration | 30% |

| Significant Amenity Landscape | 75% |

| Outstanding Natural Landscape | 25% |

| K017 Ecological Site 42,000 hectares in extent | 25% |

| Dominant Ridgelines | Yes |

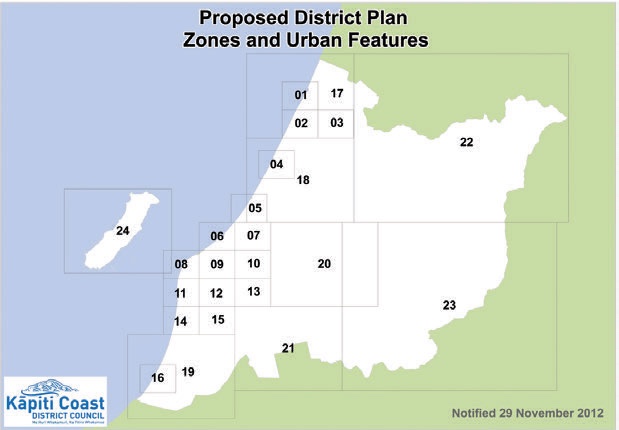

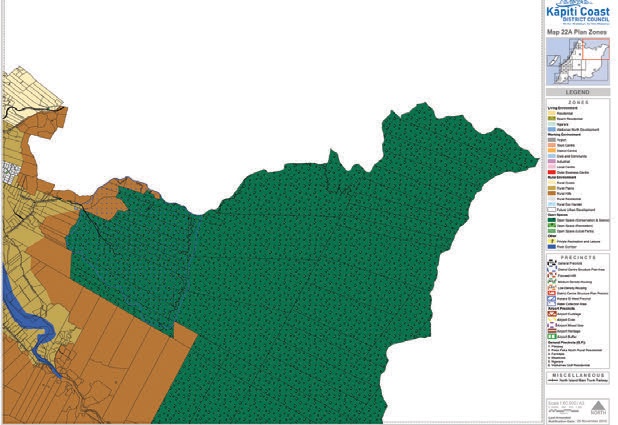

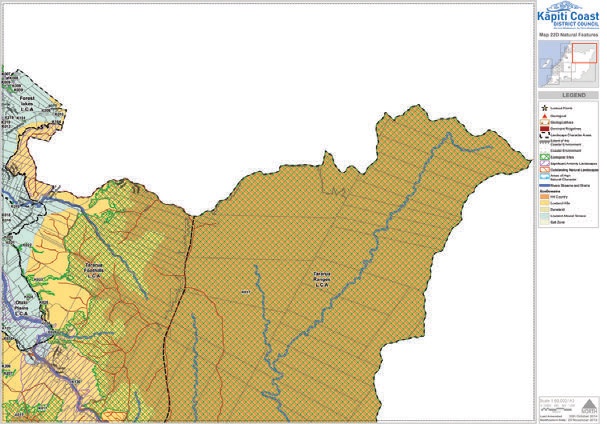

When we received the plan we discovered that it consisted of over 2,500 pages split over four binders. While the organisation of the material had some logic to it at least for the authors, the provisions applying to a particular property were spread throughout the document. The first stage in studying this or any other plan is to try and identify how the council has classified the land. This is normally done by finding the property on the various maps and then trying to interpret what the various colours, shadings and patterns mean. In our case we discovered that they had put multiple designations on our land.

The next stage was to find out what these designations meant and here we had to painstakingly search through the 2,500 pages using the Adobe Acrobat search function, looking for anything related to these provisions. We soon discovered that the plan, if implemented in its proposed form, would severely affect our ability to make use of our land for forestry or any other purpose. In particular, the proposal to designate approximately 25 per cent of our property as an ecological site would, under the proposed provisions, make it almost a no-go zone.

The submission process

We had been warned that as many rural residents as possible needed to put in separate submissions as −

- Both the quantity and the quality of submissions influence Commissioners

- If you do not submit, you can be locked out of the later stages of the submission process.

To make submission writing easier, a group of rural people interested in getting the plan changed started meeting informally to swap information about the plan and ideas for submissions. Based on material from this group and our own analysis of the proposed plan, we put in a submission seeking two basic things −

- That as many as possible of the designations be removed for our land

- That where the designations can be justified, the conditions applied are made as reasonable and practicable as possible.

Leaving aside our concerns regarding the land we owned, the proposed plan was also not at all supportive to forestry in the district. The planners’ attitude to forestry can be judged by the following quote from the rural chapter of the proposed plan −

The plan also recognises the unique operational characteristics of some primary production activities – such as plantation forestry and extractive industries – which are characterised by nuisance effects.

No mention was made in the plan of the income that forestry brings to the district directly and indirectly nor of the eco-system benefits of properly managed forestry operations. To try to correct this, we worked with the Wellington Branch of the NZFFA to prepare a submission, commenting on the forestry specific aspects of the plan.

Cross submissions

Once the over 500 submissions were received, the council called for cross submissions. This is an important part of the process as it allows submitters to −

- Say which of the other submissions they support

- Oppose the submissions that will have negative effects on their properties.

The second part above is particularly important. Submitters come from many different points of view and a careful study of the submissions is required to identify those which are proposing even more stringent requirements than those already in the plan. As would be expected, our cross-submission supported submissions from other members of our informal group as well as the submissions lodged by other who had similar views to us.

Coastal provisions

Another group that was significantly affected by the proposed plan were those with dwellings close to the coast. As part of the plan process, the council had commissioned a study of coastal erosion hazards and this had resulted in the council −

- Mapping significant areas of coastal land as Coastal Hazard Management Areas

- Prohibiting owners of the large number of valuable properties in these areas from doing anything but minor maintenance on their dwellings

- Making the rules effective immediately and adding notes to all their LIMs to warn potential owners of the zoning.

This was done as with the rural provisions with minimal consultation and, as can be imagined, led residents in this area to mount a strong and well-funded campaign against the proposed plan. While the interests being faced by the coastal and rural groups were quite different, we had one objective in common, to get the council to significantly change the plan. We explored working with this group but our styles of involvement were different and, while we kept in touch with what they were doing, we continued with our own separate advocacy.

A change of council and a change of attitude

It became clear to both groups that the then-current council was not particularly interested in listening to our concerns and this led to a general feeling that the only way to achieve change was to change the council. In the October 2013 elections the Mayor and several councillors were not re-elected. We would like to claim that we had some influence on the result, but in reality it was probably the well organised campaign by the coastal ratepayers which had the most effect.

With the change of councillors came a significant change in the planning area. Several senior officers resigned and their replacements proved to have a much more inclusive attitude. They wanted to work with the rural and other sectors to find solutions that work for both the environment and the rural ratepayers rather than concentrating their energies on opposing any change to the proposed plan. Their attitude to us was demonstrated by the saying we heard from councillors and staff alike −

‘We see forestry and farming as activities that should be supported in the rural sector’ and ‘We see the owners of rural land as the best stewards of their land.’

Another significant change was that council officers saw us as a positive influence over the proposed plan and asked if they could work more directly with us to achieve a win for both parties. Therefore the Rural Issues Group was born – the same informal group of submitters but with input from time to time from council officers. Since late 2014, the Rural Issues Group has generally met on a monthly basis with some meetings having presentations from and discussions with council officers and other being ‘Rural Issues Group only’ meetings.

The review

In late 2014 the new council decided that it was appropriate to bring in an independent planning expert Sylvia Allen and a legal expert Richard Fowler, QC to −

... determine whether the plan should continue to be progressed through the hearings process, significantly changed, be withdrawn or some other process followed in order to best achieve the [stated] goal.

The Council’s stated goal was defined as –

To have a District Plan that represents good practice, is comprehensible for users, is easily accessible and this is achieved fairly in the most cost effective way.

The reviewers met with a wide range of interested parties including most members of the Rural Issues Group. They considered various methods for moving forward including withdrawing the plan and starting again and recommended as follows −

- The council proceed with the proposed plan on the basis of a modified process of hearing and making decisions which includes all elements set out in section 5.5 of this report.

- A detailed implementation plan including resourcing and timetable is developed to progress the proposed plan in accordance with the first recommendation. A communications plan to keep the community informed would be a necessary part of the implementation.

- The council undertake a detailed review of the rules of the proposed plan having legal effect and clarify these provisions as soon as possible.

- The council resolve to withdraw, from the proposed plan, the coastal hazard management areas on the plan maps along with the associated policy section and rules, and clarify the parts of the operative District Plan which provide stop-gap coverage relating to coastal hazards.

- The council develop an implementation plan to progress work on the coastal erosion hazard assessment, and other aspects of coastal hazard management. The implementation should build on the work already done and incorporate adequate and appropriate communications and consultations provisions, including a role for an advisory group as described in section 6.4 of this report.

- At an appropriate time or times the council proceeds with a variation or variations to include suitable and relevant policy, methods and rules in the proposed plan to address the district’s coastal hazards.

- The council only withdraw the whole of the proposed plan if it is unable to resource the methods we recommend for proceeding through Option 4, or if it considers the residual risks identified in section 5.6 of this report are too high.

As can be seen from the above, the coastal group had achieved their aims − withdrawal of the coastal hazard management areas on the plan maps along with the associated policy section and rules. In addition the reviewers were recommending a more conciliatory approach to other submitters, such as ourselves.

On the topic of misleading the ratepayers when notifying the plan, the QC said that while it was ‘unfortunate’ it was ‘not a fatal flaw’ – in other words it was not, of itself, a reason that a judge would throw out the plan.

As a group, the Rural Issues Group needed to decide whether we should agree with the reviewers that the plan should proceed or whether we should call for it to be scrapped and start again. This engendered considerable discussion and some division within the group but eventually we decided that, given the amount of work we had done on the plan, it was better to try and fix it rather than to have to start from scratch. We therefore supported the reviewers’ recommendation at the council meeting called to consider it and the council agreed.

The Rural Issues Group after the review

Since the review, the Rural Issues Group has addressed a number of the issues which concern all of us with the aim of −

- Reducing the areas of our land designated as ‘special’

- Removing or introducing practicality into the rules that apply to these special pieces of land.

We have had some success in these areas and the council itself has helped by removing entirely the ‘Priority for restoration’ and ‘Dominant ridgeline’ classifications. The council has also shown itself willing to discuss the methods used to classify land and the rules or incentives that should apply to land classified as such.

One very controversial area remained − what land should be classed as ecological zones or outstanding/ significant natural landscapes. To address these questions, a pilot group was set up under the Rural Issues Group in which three representative properties belonging group members were chosen to be reviewed. The process has worked relatively well so far with pilot group members being happy with the result of the landscape review and looking forward to a good result in the ecological area. In parallel with the work above, council officers and consultants have been working on a ‘Submitter engagement version’ of the proposed plan. This is basically a copy of the original plan marked up to indicate the changes that they are planning to recommend to the Commissioners when hearings commence.

While we are pleased with progress in this area, we still have concerns that the majority of the proposed changes are to rules in the original proposed plan and do not answer the more fundamental question as to whether the rules are required in the first place. As an example, the rules on the width of tracks have been relaxed somewhat but the question as to whether rules on track width are required, as there is a cost disincentive associated with wide tracks, has not been addressed.

Overall, the author, who chairs the Rural Issues Group is happy with progress but knows that significant effort will continue to be required if we are to have a district plan which benefits all residents of the Kapiti District. Unfortunately it will be at least 2016 before we know to what extent our efforts have been successful.

Lessons for others

As noted at the beginning of this article, one of its aims is to provide others facing a district plan change with ideas as to what they can do to influence what happens in their district. While every district and regional plan process will be different, I believe that there are some principles that apply irrespective of the area you are in:

- Try to become involved with your council as early as possible in the process. Even if they refuse to get involved, as happened in our case, the fact that you tried and were repulsed adds strength to your arguments before the hearing commissioners.

- Work with others in your area to bounce around ideas and build up your case. Our informal working group, which became the Rural Issues Group, has provided both practical and emotional support to members and has benefitted more recently by having Federated Farmers associated with the group.

- Make sure you take all opportunities to be part of the process – both before and after the proposed plan is notified. In particular, it is important that you submit and cross-submit. If you do not, you can be locked out of further involvement in the process.

- Remember that it is important to get involved with elected members and staff. The messages you give to these groups will need to be different but neglecting communications with either group is likely to weaken your position.

Don Wallace is member of the Executive and of the Wellington branch of the NZFFA.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand