PESTS AND DISEASES OF FORESTRY IN NEW ZEALAND

Dutch elm disease caused by Ophiostoma novo-ulmi and vectored by Scolytus multistriatus

Scion is the leading provider of forest-related knowledge in New Zealand

Formerly known as the Forest Research Institute, Scion has been a leader in research relating to forest health for over 50 years. The Rotorua-based Crown Research Institute continues to provide science that will protect all forests from damage caused by insect pests, pathogens and weeds. The information presented below arises from these research activities.

From Scion publication Forest Research Bulletin 220. An Introduction to The Diseases of Forest and Amenity Trees in New Zealand,

G.S.Ridley and M.A. Dick 2001.

Species: Ophiostoma novo-ulmi (Ascomycete)

Common name: Dutch elm disease

Host(s): Many Ulmus spp. and Zelkova spp.

Country of origin: Asia, Europe/ or possibly North America.

Symptoms: Include yellowing of foliage, wilting of the crown, followed by dieback and mortality (Fig. 71). Typically, symptoms appear first on one or several branches before spreading to other parts of the crown. Characteristic brown streaking in the xylem of the infected wood occurs.

Disease development: Fungal spores are carried on the bodies of scolytid bark beetles. Only one such vector, Scolytus multistriatus, is present in New Zealand (Fig. 72). Beetles feed in twig crotches and the fungus gains access through the feeding wounds. The fungus multiplies rapidly in the xylem, effectively blocking the water-conducting tissues, and also produces wilt-inducing toxins. The fungus can be transmitted from tree to tree through root grafts. Infection occurs in summer as the beetles do not fly if temperatures are below 20°C.

NZ distribution: Limited distribution in suburban areas of Auckland city and Napier. Note that the vector is absent from Napier.

Fig. 71: Typical wilting of Ulmus sp. caused by Ophiostoma novo-ulmi

Economic impact: Dutch elm disease is a vascular wilt caused by two very closely related species of Ophiostoma. There have been two major epidemics of the disease. The first, caused by Ophiostoma ulmi, began early last century in Europe (first record in France 1918). It soon spread across much of Europe and reached North America in the late 1920s on elm veneer logs imported from Europe. This first epidemic was relatively mild and recovery from disease was not uncommon. The second, far more destructive epidemic, which was caused by the more virulent 0. novo-ulmi, began in the late 1960s and has continued until the present time. In North America, the native Ulmus americana is extremely susceptible and approximately 70% of the mature trees in the United States have been killed. A large proportion of the mature native elms across Europe have died (more than 25 million of an estimated 30 million elms in the United Kingdom alone). Both rural and urban landscapes in these countries have been radically altered as a result. In some countries (e.g., Canada, United States, and England) local authorities at great expense mounted eradication campaigns but these all failed. Initially, failure was due to insufficient knowledge of the epidemiology of the disease, and latterly a reduction of effort by some local bodies resulted in re-infestation of neighbouring areas where effort was maintained. Today, despite rigorous sanitation measures having slowed the spread of the disease in many places, and the development of a number of chemical and biocontrol treatments to restrict development of infection in individual trees, elms continue to die in Europe and North America. These measures and treatments create a very significant cost to local authorities.

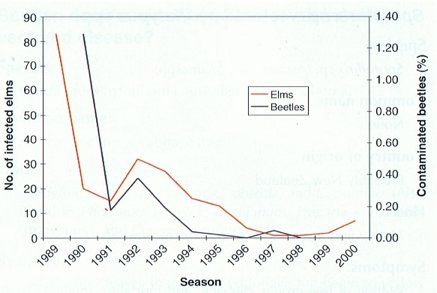

Fig. 72: Scolytus multistriatus breeding galleries and larval tunnels under the bark of dead elm wood

Control: Following the discovery of Dutch elm disease in Auckland in 1990, a survey of the distribution of the disease was completed within a week and a decision to attempt eradication was made. This was based on two premises; first, was the survey findings, which showed that the disease was confined to a relatively small area. The second was that, as the cost of felling and disposal of infected trees would have to be incurred anyway, the only major additional expenditure would be that associated with the detection surveys and publicity. The strategy implemented was to locate and destroy every infected tree, and all fallen material suitable for beetle colonisation, before the beetles breeding in it had time to complete one generation (about 6 weeks in summer in Auckland). A network of sticky traps containing an aggregating pheromone of S. multistriatus was set up in late 1990 in the greater Auckland area. The objectives of the trap network were to determine the distribution of S. multistriatus populations, to estimate beetle population densities, and to find the areas where beetles carrying 0. novo-ulmi were present. When infected beetles were found, additional effort was put into locating the source of the infection if there were no known infected trees within the flight range of the beetle. This unknown source may have been an elm tree, which had not been located during the initial surveys, or elm wood, which had been stored for firewood. The number of trees infected by Dutch elm disease has been low (83 in the first season, only two in the 1999-2000 season and only one for each of the previous two seasons). Numbers of infected trees and contaminated beetles found from 1989 to 2000 are shown in Fig. 73. Since 1998 all of the diseased trees identified had been infected in an earlier season and the fungus was contained within an inner growth ring. This type of cryptic, asymptomatic infection of old wood poses the greatest threat to the potential successful elimination of Dutch elm disease from New Zealand. In 1993 a small infection area was discovered in Napier. Intensive pheromone trapping failed to detect any Scolytus multistriatus and the source of this infection remains unknown. As the elms were linked through their root systems a decision was made to remove all the elms in the infected area and this was carried out in 1997.

Fig. 73: Number of infected Ulmus spp. found 1989-2000 and the percentage of trapped beetles contaminated with Ophiostoma novo-ulmi

References: Dick et al. 2000; Gadgil et al. 2000; Forest Research Institute 1990; Sinclair et al. 1987.

This information is intended for general interest only. It is not intended to be a substitute for specific specialist advice on any matter and should not be relied on for that purpose. Scion will not be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, special, consequential or exemplary damages, loss of profits, or any other intangible losses that result from using the information provided on this site.

(Scion is the trading name of the New Zealand Forest Research Institute Limited.)

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand