See also:

Case Study: Rutherfords

Forestry in the hill country: Sustainability and survival

Dugald and Mandy Rutherford have farmed their home block Melrose since 1975. The 3,477 ha property lies 20km inland from Hawarden, North Canterbury, and ranges from moderate to hard hill country through to classic South Island high country.

The property was part of the original Horsley Downs Estate until subdivision in the early 1900s.

Melrose experiences all the extremes of inland Canterbury weather - droughts, snow, frost and gales. However the major climate challenge to farming in this area is snow. Dugald says his grandfather twice faced five feet of snow overnight which is potentially devastating for a sheep farmer.

From sheep and cattle Mandy and Dugald have diversified into deer farming, tourism and forestry, and currently farm some 5240 sheep, 310 cattle, and 300 deer (6100 su) and have 200 ha of planted forests.

Forestry and trees are inextricably entwined with Mandy and Dugald’s farm management. They share each other’s enthusiasm for trees and as former Husqvarna South Island Farm Foresters of the year exemplify the way forestry and thoughtful land use go hand-in-hand.

They have three main reasons for planting trees (apart from their obvious pleasure in growing them). The primary one is to spread their financial risk, as trees continue to grow even when extreme weather events affect their income from farming. They also plant trees because on some parts of Melrose forestry is simply a more sustainable, productive use of land than extensive grazing. The third reason is for succession planning and to create a retirement income. Agroforestry blocks also provide vital shelter for stock in summer sun and snow storms alike.

Melrose – its history & location

Dugald and Mandy Rutherford have farmed their home block Melrose in partnership since 1975. The 3,477 ha property lies 20km inland from Hawarden, North Canterbury, and ranges from moderate to hard hill country through to classic South Island high country.

In subsequent years they purchased Haystacks, 332ha of bare land 6km further up Virginia Road, and in 2000 purchased Woodford, 126h of cultivated flat land at the bottom of Virginia Road.

The home block of Melrose straddles the headwaters of three flow-sensitive catchments -- the Waipara (764 ha), Okuku (2500 ha) and Waitohi (213 ha).

All the properties were part of the original Horsley Downs Estate until subdivision in the early 1900s. In the subsequent decades Melrose had a number of owners, most of whom lost money. The property was also owned for some years by the BNZ who rented it out.

Land use was traditionally extensive fine wool sheep grazing and the only land management tool was burning on an approximately three year cycle.

Dugald’s father purchased the property in 1948 and from the 1950s, with the use of top dressing, fencing and tracking, was able to make a profit. He introduced cattle in the 1960s. In the 60s and 70s the practice of burning was curtailed under the supervision of the catchment board, and a much more conservative approach was taken to soil health. This has lead to an increase in scrub cover in general. (Fortunately there are no exotic weeds such as broom.)

These contrasting views of Melrose show the natural increase in scrub cover after burning ceased.

Land description

The three properties range in altitude from 330 m to 1300 m above sea level. The land use classification for the hill properties is predominantly Class VI, VII and VIII (see Table 1) over a total hill area of 3,809 ha. (This system ranks land according to its potential for sustainable production. There are 8 classes ranging from Class I "highly versatile land" to Class VIII, land with extreme limitations.)

Rutherford hill property LUC

| Class | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | Bush |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | 80 | 1812 | 1089 | 688 | 145 | ||||

| Percentage | 2 | 47 | 29 | 18 | 4 |

Soils

The predominant soil type is greywacke-based and is mainly Hurunui Hill or Hurunui Steepland, depending on topography.

Vegetation

The original land cover was forest and Melrose enjoys deep forest soils as a result. However most of these forests were gone before European settlement. As one of the original settlers in the area, Dugald’s grandfather witnessed many further changes in the vegetation cover as first deer and then possums arrived. There were also several rabbit plagues. However Dugald says it’s good country in that they don’t have noxious weeds. The current land cover also includes 145 ha of beech forest.

Climate

Melrose experiences all the extremes of inland Canterbury weather - droughts, snow, frost and gales - the thermometer under cover on the Rutherfords’ back door verandah has recorded temperatures ranging from -16°C to 38°C.

Rainfall records have been kept from 1948 at Melrose and are recorded for NIWA, with a long term average of 960mm p.a.

Rainfall

Long term average for Melrose (460m asl): 960mm (562mm – 1367mm)

Long term average for Woodford (330m asl): 764 mm

Two years three month record for Gola Peak (1255m asl): 1084mm

However the major climate challenge to farming in this area is snow. Dugald says his grandfather twice faced five feet of snow overnight which is potentially devastating for a sheep farmer. (His great-grandfather was actually bankrupted by two similar snowfalls on Godley Peaks in the 1890s.)

Farm Operation

When Dugald and Mandy started their tenure of Melrose in 1975 the property carried 2750 sheep and 175 cattle (3400 su equivalents). They diversified into deer farming, tourism and forestry, and currently farm some 5240 sheep, 310 cattle, the 300 deer (6100 su) and have 200 ha of planted forests. This represents a 39% increase in the stocking rate/effective ha.

The roles of trees at Melrose

Forestry and trees are inextricably entwined with Mandy and Dugald’s farm management. They share each other’s enthusiasm for trees and as former Husqvarna South Island Farm Foresters of the year exemplify the way forestry and thoughtful land use go hand-in-hand.

However Dugald’s knowledge of and involvement in forestry goes well beyond that of most farmers with a passion for trees. He graduated with a bachelor's degree in Forestry Science in 1971. He is a past president of the New Zealand Farm Forestry Association, and currently president of the North Canterbury branch of the New Zealand Farm Forestry Association, chairman of the Anglican Schools Forestry Trust (administering 2000 ha of forest in the Wairarapa and currently harvesting 600 ha) and co-founder and chairman of Warren Forestry (the company has planted and manages 1500 ha of joint-venture forests in Canterbury and Marlborough).

He doesn’t know where his love of trees came from, but it’s obviously something of a family tradition. His grandfather had his own nursery when he first came and settled next door, when the farms were first broken up. He planted trees initially because there was no firewood and they used to have to go long distances over the hill to get fuel.

When Dugald was still at school his father planted some trees up behind the house. Dugald started pruning them, although he still doesn’t quite know why, recalling it was actually before Wink Sutton was doing his research. He went off to Canterbury University intending to start first year veterinary, but says when the forestry course was announced, straight away he just knew that was for him.

“I’ve always had this real interest and even at uni I’d come home and plant trees,” he says. “I was so lucky to have had that interest early. When my father retired he got really enthusiastic about planting trees. A lot of people only get that interest later in life, but if you have it when you’re young then you can really enjoy it all the way through."

Why forestry?

Planting began on Melrose in 1975, with two aims. The first was the intention to plant a block every year so that in the future there would be an annual cash flow from something other than stock.

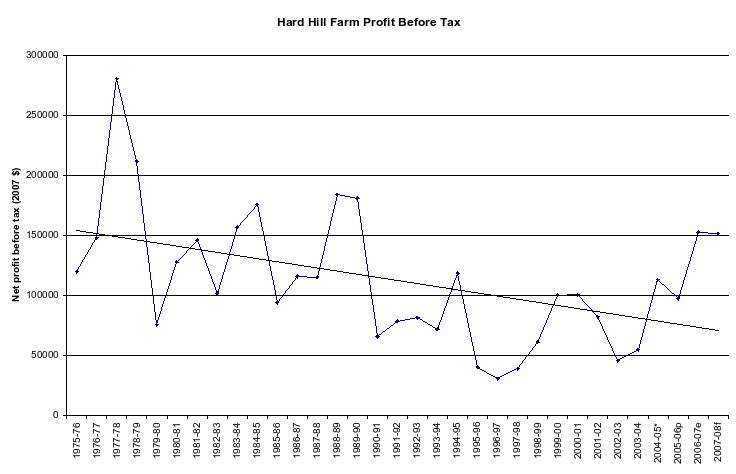

“I’ve always believed income from forestry would be a good complement to our farm income,” says Dugald. “Over the years, snow, drought and animal diseases such as TB and footrot have all caused us significant financial losses. These aren’t a risk to appropriately sited forests.”

He says forest product values have kept ahead of inflation for the past 100 years and he believes this trend will continue, for a number of reasons: As access to logs from natural forests becomes more difficult due to environmental pressures, or the available forest becomes more remote, then the real price of wood will continue to increase. The majority of clear felled forests in the tropical areas are being converted to agriculture or palm oil plantations and there appear to be few future competitors in wood production for a plantation owner in New Zealand.

“This contrasts markedly with agriculture where we have faced a 3% real decline in values annually.

In fact farming here is not really a sensible thing to be doing … every year that I’ve been on the place our actual real income has gone down. We’ve had to double our stock units just to stand still but what options will the next generation have?”

Dugald is concerned that simply continuing to increase stocking rates on marginal hill country is not a sustainable or realistic option because it will have a number of negative effects, including:

- More stock movements through waterways, to the detriment of water quality. He says there is just no economic solution to combat this problem on their class of country.

- An increase in fertiliser use, which will also put pressure on water quality. This may create a further problem, in that as the price of phosphate rock and elemental sulphur rises and agricultural returns diminish, the first place phosphate application will be cut is on Class VI country, leaving a modified environment in a vulnerable state and in turn encouraging the spread of hieracium.

- Removal of woody vegetation to grow more grass, pushing grazing into more marginal areas. This will reduce biodiversity, above-ground stored carbon and, most critically, reduce low level shelter for stock. Areas bared by spraying, burning and intense grazing are then vulnerable to soil erosion if stressed by drought, rabbit invasion or cessation of fertilising.

A forest owner on a farm also has other revenue generating options to consider, including carbon sequestration, and the establishment of the forests under the Permanent Forest Sinks Initiative as well as other possibilities such as bioenergy/biofuel or biochar (depending on local scale).

The biological imperative

The second reason for forestry at Melrose is that the Rutherfords believe there is a compelling biological reason for planting trees in their area. On some parts of Melrose forestry is simply a more sustainable, productive use of land not suitable for more intensive grazing (3-4 su/ha compared to 1 su/ha) which would be much more profitable in trees.

On their better country, where they can get a return from fertiliser and keep on top of scrub reversion, pastoral farming will probably prevail. However on undeveloped country, which they describe as having suffered 150 years of burning and grazing, continuing these practices is not a sustainable option. Some of this land is more remote, so it is significantly more expensive to fly fertiliser onto. Other areas have a depleted or very thin A horizon (DOOKS 16) within the soil profile, so they see forestry is the only sustainable solution at present.

Trees can exploit the mineral bank in the sub soil that grass and clover can’t, and the only mineral that needs to be added for good growth is boron for radiata pine. Forests also have positive effects such as reducing soil erosion and improving water quality. Where forests replace stock, stock movements through waterways are reduced, lowering both faecal matter and fertiliser in the waterways.

Shingle country

“A lot of our country looks like this, almost bare shingle - no grazing on there, yet you can put a crop of trees on and they’ll do extremely well,” says Dugald. “There’s nothing much you can do with this. You could spray that scrub, bare it off and maybe put some fertiliser on, but where you’ve got shingle nothing will grow anyway, so it just seems to make sense to put trees in a place like this. Maybe this land has been burnt too often throughout its history so that topsoil has been eroded, but we’ve still got that good sub soil.”

“A lot of our country looks like this, almost bare shingle - no grazing on there, yet you can put a crop of trees on and they’ll do extremely well,” says Dugald. “There’s nothing much you can do with this. You could spray that scrub, bare it off and maybe put some fertiliser on, but where you’ve got shingle nothing will grow anyway, so it just seems to make sense to put trees in a place like this. Maybe this land has been burnt too often throughout its history so that topsoil has been eroded, but we’ve still got that good sub soil.”

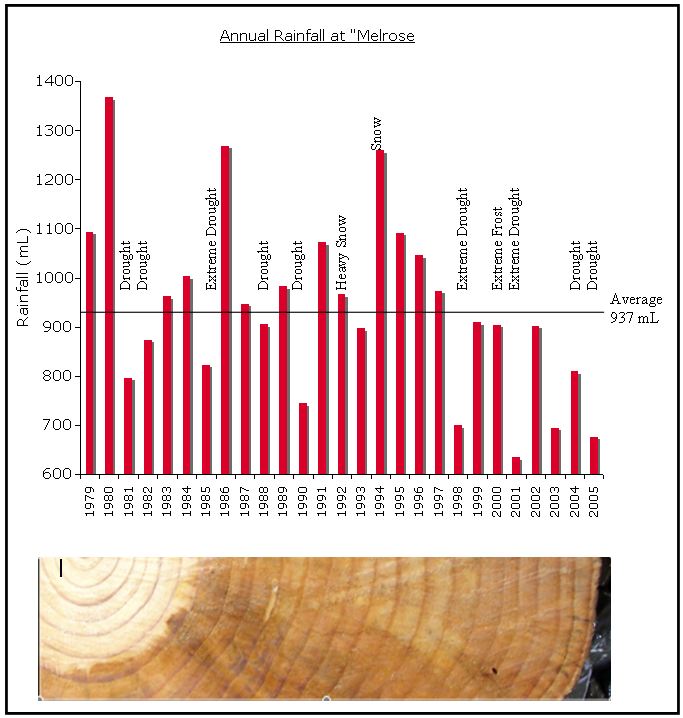

With their deep root systems forests are less susceptible to climatic variations. However after once hearing the comment that trees stop growing during Canterbury droughts, Dugald thought he should find out for himself.

“I was looking at tree rings and thinking out on the Plains they might stop growing - they don’t shrink but they don’t grow - but up here there’s the deep subsoil and they’re tapping into that so they’re very constant.”

Dugald set off to find a tree whose annual growth rings could be matched up against actual rainfall, as well as extreme weather events such as heavy snow, drought, extreme droughts and extreme frost, in order to demonstrate the minimal effect local climatic variation has on tree growth. The result is shown in Figure 2, where despite tremendous variations in rainfall and significant events the growth of a radiata pine tree planted in 1975 and harvested in 2005 remains extremely consistent. All of those events have an effect on the property’s income from agriculture and yet the trees are able to “just plod on” he says.

Planning for retirement

The third reason for planting forests concerns retirement and inheritance planning. As part of their succession strategy, the 200 ha of pines that Mandy and Dugald have progressively planted will, when sustainably harvested as each woodlot matures, generate income from some 4000 tonnes of logs annually, allowing them to move off the farm.

Forests can grow into large capital assets with a good cash flow, says Dugald, and will give them and the next generation more options.

“Pure pastoralism generally generates too small a cash flow to allow the retirement of one generation and the succession of the next without crippling debt. By contrast, because we have 200 ha of forestry we now have the potential to fund our retirement in perpetuity, which creates greater flexibility in terms of succession planning. In the future I see all these reasons for planting becoming more relevant as the next generation looks to make a living off Melrose. I believe some 2000 ha of our property is unsuitable for any exotic forestry planting because of the high risk of wilding spread (unless sterile trees are developed), but of the remainder of the land up to 1000 ha would be suitable for tree planting.”

What trees and why?

The initial plantings used the Forestry Encouragement Grant, and as cash was tight, the areas planted were the minimum 2 ha, in corners that required little fencing. Regimes followed Forest Service standards and involved P. radiata , Douglas fir and E. delegatensis. After the finish of the Grant Scheme the Rutherfords began fencing for deer. In the process they took advantage of the new fencing and the old sheep fences to plant a number of blocks that have since either ended up in the deer farm or are on the boundary of it. The deer love conifer forests even though they have native cover in all their paddocks.

“We made the mistake of putting some trial plantings around the boundaries of the deer farm and inevitably when a wild stag turns up he wreaks havoc on any small trees,” says Dugald.

Dugald says radiata under their conditions has performed well under the agroforestry regime and he think they will revisit this regime now they have seen how the crop has developed. The last agroforestry block was planted in 1991... the 1992 planting involved planting a series of small woodlots over a block, placing them for shelter and on spots that grew little grass. They then shut the gate for 4 years.

Douglas fir has been planted on the higher, colder and steeper country. These higher volume crops will have to be harvested by hauler. All plantings have been planned with access to the logging road in mind. The property is long and narrow and the main D. Fir planting is some 6 km from the county road. However Dugald notes they are blessed with ideal road making material only a blade depth below the surface. Some areas of macrocarpa, Pinus nigra, larch and Eucalyptus nitens have been planted, all of which do well if sited correctly. One area of P. Nigra was established using aerial seeding, which after a slow start is now well established. The key to its success was little or no grass completion.

A key to good radiata growth in the area is boron. The Rutherfords have found that on soil types with little or no organic matter their trees were little better than gooseberry bushes without an application of boron. As a result all radiata receives boron shortly after planting.

Most of the radiata has been pruned to 6m. Pruned wood has proved to be of good quality with few defects. On the other hand because of the altitude and latitude, their radiata will always be of low density - a negative for their structural grades. Pruned stocking / ha varies between 150-300 sph with most of it pruned to 6m. In the agroforestry blocks all unpruned trees are thinned, otherwise mustering is impossible.

Douglas fir is planted at 1200-1400 sph and thinned to 800 sph at 16m height -a difficult job as the trees will not fall. In areas with good access further commercial thinnings are planned to produce a final stocking of 450 sph.

Macrocarpa has been planted at 800 sph with pruning up to 6m on up to 300 sph. Canker has become an issue on the harder sites. In the past there was no sign of the disease but it has appeared in recent times, causing malformation and some deaths on the colder, more exposed sites where the trees are not doing so well. E. nitens does very well at Melrose, as long as it is kept up out of the frost pockets, with good results planting 100 sph for final stocking. Form is immaculate and with pruning up to 8 m they are a magnificent sight, but 15 m high trees have been killed outright by frost on the wrong site, during a period when -16°C frosts were experienced for a week).

In recent times the Rutherfords have reduced their plantings while they coped with the silviculture of the planted areas and educated their four children.

Planting on Melrose has now moved into a new phase with the children establishing 10 ha of radiata last year and their preparations are under way for this year’s planting using the Afforestation Grant Scheme. Things have come full circle.

This list of blocks planted does not cover amenity plantings and native areas fenced off, of which there have been many. “Nurserymen must rub their hands together when they see us coming,” says Dugald, “as over the years we have tried literally 100s of species and found most of them unsuitable. One thing we have learnt is that a true trial for a new species requires trying it over a range of sites. One that springs to mind is Abies bractiata which we saw doing well at Twizel. Any we planted on lower slopes or near a creek have really struggled with frost but one we have high on a ridge is doing really well.

Dugald says that species such as Douglas fir and Lawson cypress are well adapted to snow, drooping their branches so it falls off, while Eucalyptus delegatensis actually repels the snow so it doesn’t stick at all. These grow at high altitude in NSW and are well adapted to snow.

Ponderosa pine, put in a very windy spot, has proved good at combating the wind. On the other hand trials of redwoods and stringybark eucalypts have proved less than successful in the overall harsh conditions, and Mexican oaks planted two springs ago were badly set back by frost

Nevertheless the Rutherfords continue to experiment with different species, including a 10-12 ha trial of radiata cuttings and controlled pollinated seedlings all pegged and tagged with six replications.

“Then you get into just stuff we’ve planted down the drive and the front paddock... On the hill over there we’ve got a whole block we call the Tantrum block,” he laughs. “... All his firs, picea... sitka. You go to a Farm Forestry Association conference and you get so enthusiastic, and there are all sorts of places in Canterbury to visit. We’re pretty lucky really with people like the Deans, you go to Homebush and come back enthusiastic… a lot of old homesteads, Mt Peel, Cheviot estate.”

Agroforestry

In the mid 80s the Rutherfords began their agroforestry plantings. P. radiata was used on the easier contour country where ground based logging will be possible for what will be a low volume crop. The planting pattern was normally in double rows with 10 to 15 m between rows. These blocks provided sheltered grazing for up to 17 years although there were periods when thinning and pruning debris was hazardous for new born lambs. These blocks were especially valuable during heavy snow and frost periods for cattle and deer.

“A lot of my plantations are open, and especially with the cattle on a hot summer’s day - they’re off into the shade, into the plantation. It occurs in the winter as well, when it’s really cold weather - it’s just like a shed for them really. One time I had the cattle in for a TB test in the middle of winter and I had to hold them for three days till we read them. There was a snow storm coming so I just put them into a block with a lot of trees on it where I knew there’d be shelter from the snow and some grass.”

While the popularity of agroforestry has waned, the Rutherfords say it is still valid for their particular situation. It is often difficult to achieve good tree form in an agroforestry block because of the wider tree spacings, they believe they can. Because pine trees don’t grow very fast at Melrose, even though they are planted at wide spacings the branches are still very fine, unlike other parts of the country.

Enhancing biodiversity

In many cases a forestry planting has given the Rutherfords the opportunity to protect a bush remnant or other natural feature from grazing by including these areas within the plantation boundaries and most of their plantings end up with a patch of bush or a wetland included and fenced off. It would be impossible to justify otherwise, given the cost of fencing. The reward is seeing the resurgence of beech and red tussock in the protected areas.

The Canterbury Natural Resources Regional Plan

The Rutherfords, like other forest growers in the Canterbury region, are very concerned at the impact of the Proposed Canterbury Natural Resources Regional Plan. By restricting forestry in the hill country with the aim of maintaining summer flows on the Plains, the regulation of the flow sensitive catchments will limit land use options, they say, encouraging further grazing pressure with a resulting negative impact on the environment in terms of water quality and biodiversity.

“It actually doesn’t directly affect what we do here but only because we are still below the threshold with our current planting. The whole principle of it is absolutely contrary to what I believe is the sensible thing to do for this land,” says Dugald.

The PNRRP as currently worded would require them to obtain consent for plantings in the Waipara and Waitohi catchments. Tree planting in the Okuku catchment would also require a consent under the PNRRP but the area Dugald says is most suitable for planting is likely to be less than the 15% threshold as the catchment contains most of the country he would not plant due to wilding concerns. The wilding-prone land is largely Class VII and VIII land where present vegetation cover is light to non-existent and the land cannot be mob stocked.

“If tree planting was encouraged we could face the future with confidence but the regulation potentially removes forestry company interest in purchasing land in our area. It has also removed the option of any subdivision to a joint venture or forestry company of weed-infested land suitable for afforestation, so that the better country can be improved by the farmer. Broom and gorse control on marginal hill country is almost always an unsustainable activity... ultimately the infected area will develop a full cover of exotic weeds at some stage with a consequential effect on water flow. Establishing forests on these sites early is not only cheaper, but also reduces the risk of these weeds spreading.

“The thing they’re on about is interception of the rain - the regulation says that we must maintain this country as much as possible in short pasture, with grazing regimes that discourage the establishment or growth of woody vegetation because if we were to clear everything off our microclimate of scrub, it would yield more water. This is absolutely contrary to what the old North Canterbury Catchment Board used to tell us, and what every other regional council is encouraging.”

Dugald points out that the climax vegetation for all these catchments is woody species, and that no amount of regulation can freeze time and stop non-climactic vegetation continuing its journey towards forest cover.

“I find this policy confusing. We are grazing an ecosystem containing some tussock and a lot of shrublands, all native. All these areas are attempting to return to the climax vegetation, namely forest. I have attempted to develop a mosaic on Melrose, with rare shrubs and bush remnants protected from extinction by grazing, other areas maintained in a shrub cover for protection of the soil and stock, and some areas cleared by spraying or burning.

“Natural processes don’t distinguish between native and exotic vegetation. No matter what we do, the woody reversion process will persist and all these rivers will retain their natural low summer flows.

“I have no problem with removing tall vegetation such as crack willows from our creeks as I believe they remove a significant percentage of the summer low flow. We personally have spent many thousands of dollars doing this and are close to total eradication of crack and golden Willows from our property.”

There are some 500 ha of crack willows in the Waipara catchment and the hydrologist for ECAN has calculated that the effect of removing them would actually more than double the summer low flow.

“Similarly, as a responsible forester, I have no problem with the removal of wilding trees, but what are the implications for our beech forests? These are spreading vigorously where we have reduced grazing pressure, so are we obliged to increase pressure on them again?